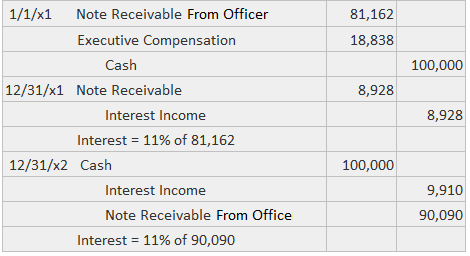

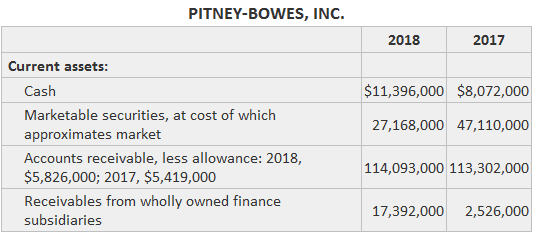

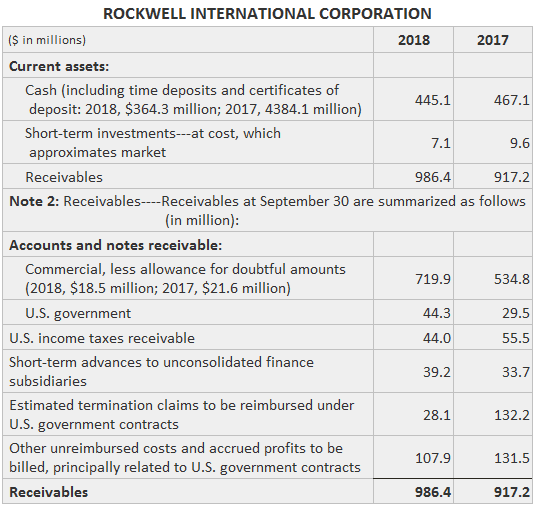

Trade receivables can take the form of either open accounts or notes. They are almost always classified as current because their normal collection period is part of, and therefore less than, the operating cycle. In general, receivables should be recorded at the present value of the future cash flows, using a realistic interest rate. This is because the difference between the face and present values of trade receivables is often immaterial. An important factor to be considered in establishing the initially recorded amount is the discount offered to the customer. Trade discounts are reductions below a list price; they are used to establish a final price for the transaction. For example, automobiles are sold to dealers at a percentage of the sticker price. This reduced price is the starting point for the accounting treatment, and the list price is not recorded by either party. Through various transactions, a firm may have a legal claim against another entity that should be disclosed as a non-trade receivable. Some of the situations in which these assets are created are: Each receivable should be classified as current or non-current. If appropriate, the receivable should be clearly identified and listed on the balance sheet. Materiality may be determined either on the basis of the size alone or on the basis that the transaction is unusual and should be fully disclosed. For example, loans to officers are often no different from other receivables in terms of their size and collectibility. However, they require special disclosure because of the fact that the loan is a non-arm's-length transaction between related parties. In this situation, stockholders may want to know that the corporate funds are being loaned to officers. Non-trade receivables, like other receivables, should be recorded initially at their present value computed with a realistic discount rate. Accounting theorists have long recognized that lending cash at a low interest rate causes firms to lose income. For example, if a firm loans cash to a supplier or an officer without charging any interest, it loses the income that it could have earned by investing elsewhere. As a result, theorists have argued that this cost should be reported. Suppose that the Sample Company engaged the services of a new chief executive in January 2021. Part of the compensation for the first year is a loan of $100,000 for two years without interest. There is no requirement that employment last beyond December 20x1. If the realistic rate for January 2021 is 11%, then this person has received a substantial benefit and the company has incurred a substantial cost. These journal entries would be appropriate over the life of the loan: Effectively, the transaction is accounted for as if the officer received $18,838 as outright compensation and loaned $81,162 at 11%. The $18,838 is recovered over the life of the note as interest income ($8,928 + $9,910). The fact that these amounts offset each other is not as important as the fact that the two fundamentally different activities of executive compensation and lending are being carried out. Further, as this example shows, the income and expense may offset each other only after several periods. If the compensation covers services extending over several years, it would be appropriate to establish a Prepaid Expense account, which would be amortized over those years. To measure income and to disclose the amount of cash expected to be realized from non-trade receivables, it is necessary to determine their collectibility. Due to their nonroutine nature, the determination should generally be accomplished on an item-by-item basis. That is to say, the firm is unlikely to have sufficient historical knowledge to apply a percentage in the same way as is done for trade receivables. Also, their special nature creates an issue concerning the timing of any bad debt losses. In general, firms write off non-trade receivables in the year in which they are known to be uncollectible instead of providing for the loss in an earlier period. This approach is acceptable for these receivables because non-collection is generally less frequent and thus not as easily anticipated. In the event that a receivable from an officer or stockholder is written off, full disclosure should be provided of the significant facts because of the related-party situation. This example shows actual disclosures of non-trade receivables from Pitney-Bowes, Inc. and Rockwell International Corporation.Trade Receivables

Definition and Explanation

Non-trade Receivables

Measurement

Notes on unrealistic interest rates

Collectibility

Example

Trade and Nontrade Receivables FAQs

Trade receivables are those accounts that arise from the sale of goods or services that the company has received an unconditional legal right to payment. Nontrade receivables are those accounts that do not meet this criterion. They include accounts with officers, affiliated companies, factoring companies, trusts for benefit of creditors, and other miscellaneous accounts.

The basic difference between these two types is that a company has received the unconditional legal right to payment from a trade receivable, whereas they have not for a non-trade receivable. In addition, there are more stringent requirements for calling an account a trade receivable.

Non-trade receivables that arise from the sale of goods or services must be reported excluding any uncollectible portion of these accounts if their carrying value exceeds $10,000. Furthermore, if the accounts are not collectible, they must be written off.

For their current fiscal period, companies can amortize their non-trade receivables if they are deemed uncollectible. For the prior year, they must write off any accounts deemed uncollectable.

Amortization allows a company to take that portion of an uncollectible account that is deemed to be impaired and account for it as though it were a sale of goods or services.

True Tamplin is a published author, public speaker, CEO of UpDigital, and founder of Finance Strategists.

True is a Certified Educator in Personal Finance (CEPF®), author of The Handy Financial Ratios Guide, a member of the Society for Advancing Business Editing and Writing, contributes to his financial education site, Finance Strategists, and has spoken to various financial communities such as the CFA Institute, as well as university students like his Alma mater, Biola University, where he received a bachelor of science in business and data analytics.

To learn more about True, visit his personal website or view his author profiles on Amazon, Nasdaq and Forbes.