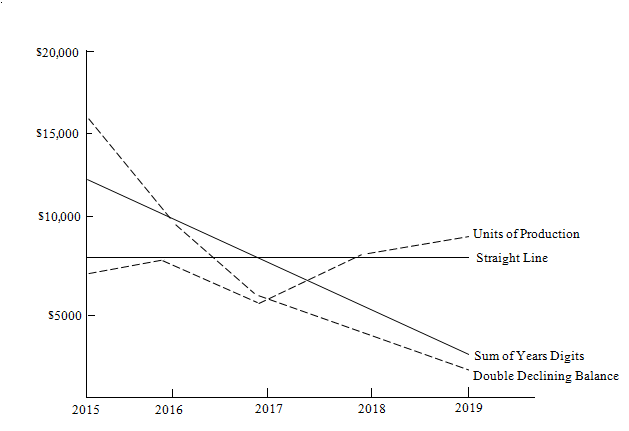

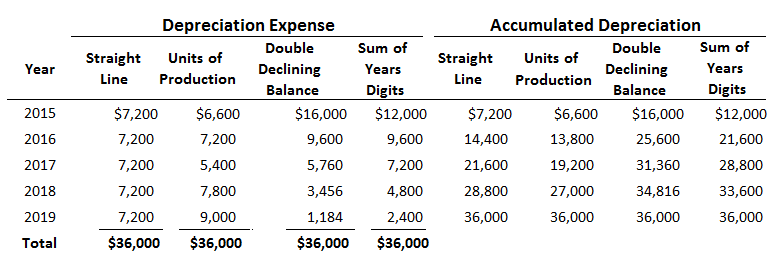

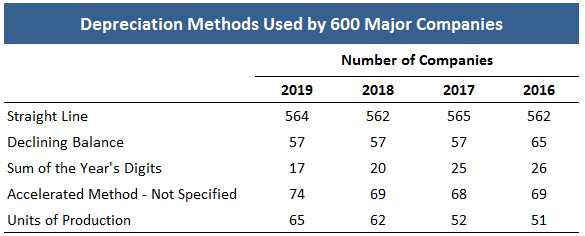

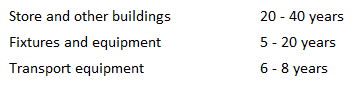

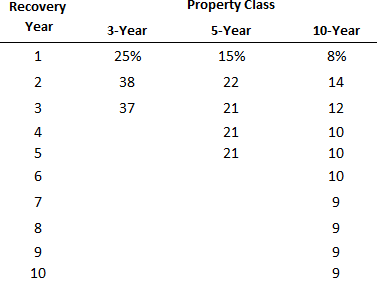

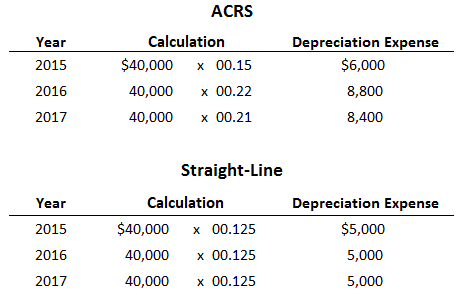

This article uses examples to compare different depreciation methods. One of the most important points to note is that in all cases, the total depreciation expense over each of the five years is $36,000. As a consequence, the balance in the accumulated depreciation account at the end of the fifth year is also $36,000 in all cases. This shows that we are dealing with various ways to allocate the same depreciable cost of $36,000. It also indicates that each method results in a different expense pattern within the five-year period. These differences are significant and can have a great effect on earnings for each year. For example, in the first year, the double-declining depreciation is $16,000, and depreciation under the units-of-production method is only $6,600. These differences tend to lessen in the middle years of the asset's life and again increase in the last years of the asset's life. However, in the last years, the differences reverse. That is, straight-line and units-of-production depreciation is greater than depreciation under either of the accelerated methods. Of course, the pattern under the units-of-production method could differ greatly in different situations. Comparison of Four Depreciation Methods Since all four depreciation methods are generally accepted accounting methods, a company's managers can choose whichever they would like for reporting purposes. In fact, it is possible to use one method to depreciate equipment and another method to depreciate buildings. All of these methods are used in practice. However, a recent survey of 600 companies, as shown below, suggested that the straight-line method is the most popular depreciation method. Theoretically, the best depreciation method is one that allocates the cost of the individual asset to the years of the asset's useful life in the same pattern as do the benefits or revenues that the asset produces. Given that different assets have different revenue patterns, all of the methods are appropriate and have relevance in specific circumstances. The theoretical soundness of a depreciation method is not, however, an absolute requirement for its use. In choosing a particular method for financial reporting purposes, management is usually more concerned with practical factors, such as simplicity and impacts on financial statements. To a large extent, this explains the popularity of straight-line depreciation. It is easy to compute and results in a constant expense spread over the asset's useful life. Because the choice of depreciation methods can have a significant effect on a firm's financial statements, current accounting rules require that a firm disclose how it depreciates its assets. This disclosure is usually made in a footnote to the financial statements that summarize the firm's accounting policies. An excerpt from the footnote included in Safeway's 2019 financial statement reads as follows: Property and depreciation Property is stated at historical cost. Interest cost incurred in conjunction with construction in progress is capitalized. Depreciation is computed for financial reporting purposes on the straight-line method using the following lives: Depreciation and amortization expense for the property of $293,732,000 in 2019, in 2018, and in 2017 included amortization of property under capital leases of $54,939,000, $55,188,000, and $54,447,000, respectively. The Economic Recovery Act of 1981 made substantial changes to the depreciation rules for tax purposes. Essentially, the traditional depreciation system was replaced by a new concept called the Accelerated Cost Recovery System (ACRS). In all but unusual circumstances, this method must be used for tax purposes. However, ACRS is not regarded as a generally accepted accounting principle and cannot be used for financial reporting purposes. Under the ACRS, the cost of depreciable property is recovered over a 3-, 5-, 10-, or 18-year period of time, depending on the nature of the asset. For example, mobiles, light trucks, and certain machinery and equipment have been assigned a 3-year life. Most production line equipment, delivery trucks, office furniture, aircraft, and so forth were assigned a 5-year life. Certain public utility property was assigned a 10-year life, and most real property such as buildings are now assigned an 18-year life. In addition to allowing a write-off over lives that in some cases are substantially shorter than economic lives, the ACRS incorporates the benefits of the accelerated-depreciation methods. To determine ACRS depreciation for a particular asset, multiply the acquisition cost (residual value is not considered) of the property by a statutory percentage. This percentage depends on when the asset is purchased, its class life, and the number of years since the asset was placed in service. The relevant statutory percentages for tangible personal property such as equipment are reproduced below. Accelerated-Recovery Table To demonstrate the use of this table and how ACRS compares with depreciation for financial reporting purposes, assume that at the beginning of 2015 a company purchases a piece of equipment at a cost of $40,000. For tax purposes, the asset has an ACRS class life of 5 years, but management estimates that for financial reporting purposes its economic life is 8 years (a 12.5% rate). The depreciation expense for 2015, 2016, and 2017 for both tax and financial reporting purposes is calculated next. Comparison of ACRS and Straight-Line Depreciation Under the straight-line method shown above, a full year's depreciation was taken because the asset was placed in service at the beginning of the year. However, for assets such as equipment, the ACRS table allows for only one-half of a year's depreciation in the acquisition year regardless of when the asset is placed in service. The 15% rate is a half-year rate—therefore, this rate is applied to the equipment even though it was purchased at the beginning of the year. Clearly, the ACRS provides substantial tax benefits in the asset's first years. That is to say, the firm's taxable income and, therefore, its tax payments are reduced when ACRS is used instead of straight-line. In the years 2020-2022, these benefits reverse. This occurs when the asset is still being depreciated for financial reporting purposes but no depreciation is being taken under ACRS. However, the fact that tax payments are being deferred until later years benefits the firm as it is able to earn interest on the money saved in the early years.

Selecting a Depreciation Method for Financial Reporting Purposes

Choosing a Depreciation Method for Tax Purposes

Comparison of Various Depreciation Methods FAQs

The declining-balance or units-of-production methods provide the largest deductions in the first year because they are based on a factor that has its largest value at the beginning of the Depreciation period.

The sum-of-the-years’ digits method provides the largest deduction in the final year because it is based on a factor that has its smallest value at the beginning of the Depreciation period.

The straight-line method produces a constant periodic expense as an asset depreciates.

Depreciation for financial reporting purposes does not consider current-law income tax effects, but generally represents what it would cost to replace the asset at today’s prices. Depreciation for tax purposes uses current-law income tax rules to determine the allowable Depreciation deduction and generally represents what it costs to replace the asset at the time of replacement.

The declining-balance or units-of-production methods provide greater Depreciation deductions than the straight-line method.

True Tamplin is a published author, public speaker, CEO of UpDigital, and founder of Finance Strategists.

True is a Certified Educator in Personal Finance (CEPF®), author of The Handy Financial Ratios Guide, a member of the Society for Advancing Business Editing and Writing, contributes to his financial education site, Finance Strategists, and has spoken to various financial communities such as the CFA Institute, as well as university students like his Alma mater, Biola University, where he received a bachelor of science in business and data analytics.

To learn more about True, visit his personal website or view his author profiles on Amazon, Nasdaq and Forbes.