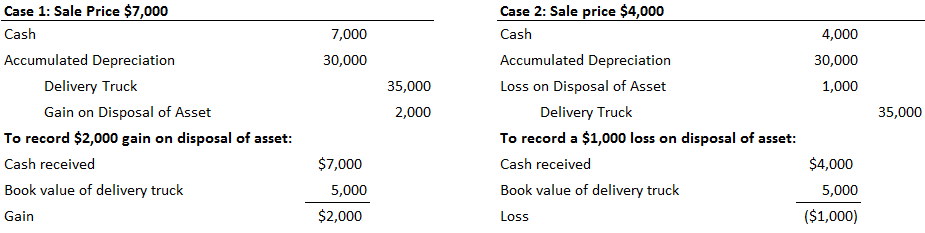

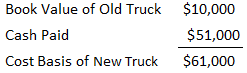

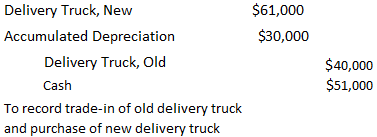

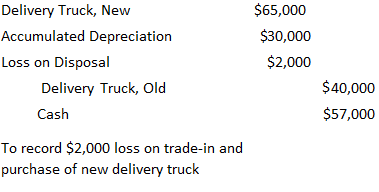

Disposal of plant assets can occur through the retirement of discarded assets, sales, involuntary conversions, or trade-ins. No matter how the disposal is accomplished, the accounting procedures are quite similar. Depreciation must be recorded up to the date of disposal and, where appropriate, a gain or loss must be recorded on the disposal. In this article, these concepts are explained by demonstrating the accounting for the sale and trade-in of plant assets. In many cases, plant assets are sold rather than disposed of for no value in return. An asset can be sold during its useful life when it has a positive book value or at the end of its life when it is fully depreciated. In either situation, a gain or loss will usually result. A gain occurs if the cash or other assets received (referred to as consideration) are greater than the asset's book value at the time of sale. Conversely, a loss occurs if the consideration received is less than the asset's book value at the time of sale. To illustrate, assume that a delivery truck with a historical cost of $35,000 and accumulated depreciation to date of $30,000 (book value of $5,000) is sold for cash; in Case 1 for $7,000 and in Case 2 for $4,000. As shown in these journal entries, both the asset and its related accumulated depreciation account are removed from the books at their full amounts. Furthermore, these examples assume that depreciation was recorded up to the date of the disposal of the delivery truck. However, in most cases, assets are sold or otherwise disposed of at various dates throughout the year. If depreciation is normally recorded at a date other than the sale date (e.g., quarter or year-end), an entry is needed to record the depreciation expense from the date of the previous depreciation entry to the date of the sale. Depreciable assets such as automobiles, computers, and photocopy machines are often traded in for new assets of a similar kind. In most cases, the trade-in allowance on the asset might be considerably different from its book value. If the trade-in allowance exceeds the asset's book value, this will lead to gain. Conversely, if the trade-in allowance is less than the asset's book value, a loss will occur. However, care must be exercised when using a trade-in allowance to measure a gain or loss on this type of transaction. Dealers such as automobile companies often set an unrealistically high list price in order to offer the customer an inflated trade-in allowance. This is done in order to make the transaction appear more attractive to the buyer. The accounting procedures that govern trade-ins are quite complex. However, for our purposes they can be stated as follows: To illustrate the accounting procedures when a realized gain on a trade-in occurs, assume that the Jackson Company trades in a delivery truck for a new one. At the time of the trade-in, the old delivery truck has a historical cost of $40,000 and accumulated depreciation to date cf $30,000 (book value equals $10,000). The new truck has a list price of $65,000, and the dealer gives the Jackson Company a trade-in allowance of $14,000 on the old truck, which is assumed to be equal to its fair market value at that time. Thus, a cash payment of $51,000 ($65,000 — $14,000) is made for the difference. Because the asset was traded in for a similar one, the realized gain of $4,000 (trade-in allowance of $14,000 less book value of $10,000) is not recognized in the accounting records, and the cost basis of the new truck is $61,000, computed as follows: The entry to record this trade-in is: At first, it may seem strange that a realized gain is not recognized in the accounting records. The APB felt that revenue should not be recognized merely because one productive asset is exchanged or substituted for a similar one. According to the APB, revenue flows from the production and sale of the goods and services that are made possible by the new asset—not from the exchange of one asset for another. In effect, the realized gain of $4,000 is just postponed. It is ultimately realized through lower depreciation charges in future years because the asset is recorded at $61,000, rather than at its list price of $65,000. Furthermore, because the new asset has a lower book value than if the realized gain of $4,000 had been recognized, a larger gain or a smaller loss will be recognized if and when it is finally disposed of (other than by another trade-in). Because of the conservatism concept in accounting, any realized loss on a trade-in must be recognized in the accounting records. For example, assume the same facts in the previous example, but now the dealer offers a trade-in allowance of only $8,000, which is now assumed to be equal to the asset's fair market value. As a result, a loss of $2,000 ($10,000 book value less $8,000 trade-in allowance) is both realized and recognized. Because the trade-in allowance is only $8,000, a cash payment of $57,000 also must be made by the Jackson Company. Finally, the new asset is recorded at the list price of $65,000. The appropriate entry is:Sale of Plant Assets

Trade-In of Plant Assets

Gain Realized but Not Recognized

Loss Realized and Recognized

Disposal of Property, Plant or Equipment FAQs

The disposal of PP&E is the strategic decision to sell, abandon or otherwise remove an asset from use.

There are a number of reasons, it includes the asset is no longer needed or is obsolete, the asset is too costly to maintain or upgrade, and the company is seeking to improve its financial position by selling off non-core assets.

The fair market value of pp&e is typically determined by an independent appraisal. This appraisal will take into account a number of factors, including the age and condition of the asset, its current use, and the current market for similar assets.

There are several benefits to disposing of PP&E, these include the improved financial position, reduction in costs and liabilities, improved efficiency or productivity, and better use of resources.

When an asset is fully depreciated, it is sold or disposed of. Assets can be sold because a firm no longer needs them or because they are no longer considered useful.

True Tamplin is a published author, public speaker, CEO of UpDigital, and founder of Finance Strategists.

True is a Certified Educator in Personal Finance (CEPF®), author of The Handy Financial Ratios Guide, a member of the Society for Advancing Business Editing and Writing, contributes to his financial education site, Finance Strategists, and has spoken to various financial communities such as the CFA Institute, as well as university students like his Alma mater, Biola University, where he received a bachelor of science in business and data analytics.

To learn more about True, visit his personal website or view his author profiles on Amazon, Nasdaq and Forbes.