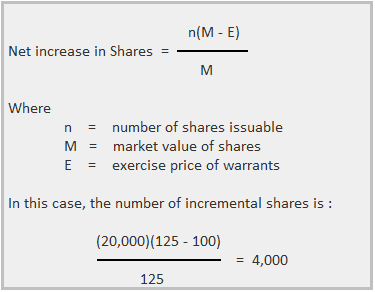

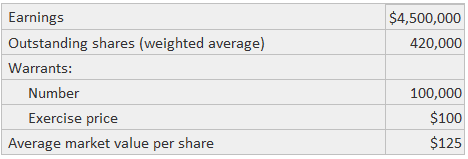

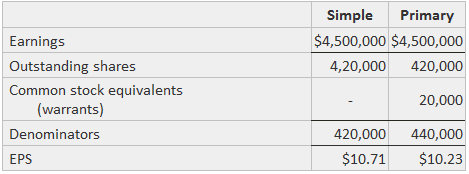

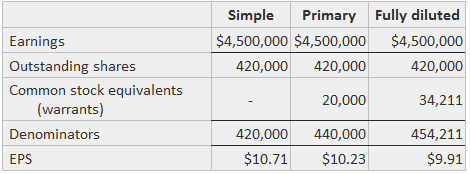

Warrants are instruments that give the holder the right to buy the stock shares of an issuing company at a fixed price until expiry. Warrants are similar to options. Stock warrants (options) have obvious potential for diluting the percentage ownership of existing shares; however, not all warrants have the same potential for immediate impact. Accordingly, GAAP allows the firm to exclude from its earnings per share (EPS) calculations those warrants that are not reasonably expected to become shares of common stock. Specifically, the accountant should not include warrants in the calculation of primary EPS if they cannot be exercised within five years. As part of the "worst-case" approach, warrants are excluded from the fully diluted EPS only if they cannot be exercised within 10 years. Further, warrants should be excluded if market conditions indicate that they are unlikely to be exercised. Warrants should be included in calculations only if the market price of the common stock obtainable has been higher than the exercise price for three consecutive months, ending with the last month of the period to which the EPS data relate. Warrants that pass these two tests (exercisability and the market test) are assumed to have been exercised. Once this assumption is made, consideration must be given to identifying what the firm would have done with the cash that it would have received if the warrants had been exercised. Without suggesting that any firm would ever use cash received from warrants to do so, EPS should be calculated as if the cash was used to acquire treasury stock. There are two effects on EPS from this assumption. First, the numerator is left unchanged as treasury stock purchases would not affect net income. Second, the impact of the assumed exercise on the denominator is reduced. This is because the purchased shares counteract the effect of the new shares assumed to have been issued. Sample Company has 20,000 outstanding stock warrants, each of which allows the holder to buy one share for $100. Thus, if it is assumed that all 20,000 warrants are exercised, the company would have $2,000,000 available to spend. If the market value of the shares is $125 per share, Sample Company would be able to purchase 16,000 shares ($2,000,000 / $125). After this, there would be an assumed increase in the denominator of only 4,000 shares (20,000 newly issued shares less 16,000 treasury shares acquired). The formula to calculate the net increase in shares is shown below. If the market value of the shares is closer to the exercise price, the effect is greatly diminished. For example, if the market value is only $102 per share, Sample Company can buy back 19,608 shares using the exercise proceeds ($2,000,000 / $102). Thus, only 392 new shares would be added to the denominator. If the market value of the stock is below the exercise price, Sample Company can buy back more shares than it would have issued because of the warrants, and the denominator would decrease. Since this result would, in turn, produce a larger EPS, such warrants are anti-dilutive and should not be considered. For example, if Sample Company's stock is worth only $86 per share, the $2,000,000 can be used to acquire 23,256 treasury shares, a quantity that would exceed the 20,000 new shares and reduce the number outstanding by 3,256 shares. A brief reflection, furthermore, shows that the warrants would not be exercised if the holder could buy the stock for a cheaper price on the market. In applying the treasury stock method to calculate primary earnings per share (EPS), the market value used to find the incremental shares should be the average market value for the covered period. Assume the following facts for Sample Company: The exercise of warrants would have produced $10,000,000 in cash (100,000 x $100). In turn, this would have been used to buy back 80,000 shares at $125. Thus, the denominator would have increased by 20,000 shares. This table illustrates the calculation of EPS: As part of the "worst-case" approach, the method used to calculate the effect of warrants on fully diluted EPS relies on the end-of-the-year market value of the shares. If it is higher than the average for the year, this change has the effects of: Using the above data from Sample Company—this time inserting a year-end market value of $152 per share—it follows that the firm can buy back only 65,789 shares of treasury stock with the $10,000,000 of assumed proceeds from the exercise of the warrants ($10,000,000 / $152). Consequently, the net increase in the denominator is 34,211 (100,000 - 65,789). These calculations would be made: As a limit on the treasury stock method, it should be used only for an assumed acquisition of up to 20 percent of the end-of-the-year outstanding shares. Any assumed proceeds remaining after the acquisition should be assumed to have been used to retire debt and then to acquire interest-bearing securities. If this point is reached, the calculation of EPS also includes an increase of earnings through reduced interest expense or increased interest income. There is also a more significant impact on the denominator because fewer shares are assumed to have been purchased back. Sample Company has warrants outstanding for the issuance of 150,000 shares at $100 each. The average market value per share is $125. Therefore, if exercising is assumed, there would be $15,000,000 cash on hand. This quantity is enough to acquire 120,000 shares of treasury stock. However, there are only 420,000 shares outstanding, with the result that only 20 percent, or 84,000 shares, can be purchased. The net result is an increase in the number of shares by 66,000. This purchase would use up only $10,500,000 of the $15,000,000 proceeds, and the difference of $4,500,000 would have to be applied. If debt totaling $2,500,000 and bearing 11 percent interest could be retired with the assumed proceeds, Sample Company would save $275,000 of interest expense (0.11 x $2,500,000). However, this expense would have been deductible on the tax return so the company must further assume that more income taxes would have to be paid. If the incremental tax rate is 45 percent, Sample Company would have had to pay another $123,750 and the net savings would be $151,250. The purchase of treasury stock and retirement of the debt would have used only $13,000,000 of the $15,000,000 proceeds. If the rate was 8 percent, the company would have earned an additional income of $160,000 but would have incurred an additional 45 percent tax expense of $72,000. The additional $88,000 would be added to purchases to find the pro forma earnings for the year. The calculation of simple and primary EPS is shown below: If the year-end market value of the common stock is greater than average, fully diluted EPS is calculated with an assumed larger outlay for the treasury shares, with less cash available for retiring debt and acquiring securities. Special consideration must be given when warrants are exercised, issued, or allowed to lapse during the year. Warrants actually exercised produce shares that are included in the weighted average from the date of issue. These warrants are regarded as common stock equivalents for the partial period prior to their exercising, and the incremental shares produced by the treasury stock method are weighted by the fraction of the year that the warrants were outstanding. Suppose that 10,000 warrants are exercised on 31 March at $10 per share when the market value is $12 per share. Thus, the incremental number of shares is 10,000 new shares less the 8,333 treasury shares, or 1,667. The incremental number of shares, 1,667, is weighted by the fraction of 3/12 for the three months that the warrants were outstanding. The 10,000 shares actually outstanding are weighted by 9/12 for the nine months from 31 March to 31 December. For newly issued warrants, the treasury stock method is applied as if they were exercised at the date of issuance. Then, the incremental shares are weighted by the fraction of the year that the warrants were outstanding. For example, suppose that 10,000 warrants are issued on 31 July for a purchase of shares at $10 each and the market value is $12 per share. Exercise would have produced $100,000 of cash, which would have been used to purchase 8,333 shares. The 1,667 incremental shares would be weighted by 5/12 for the five months from August through December. In the event that the 20 percent limit is exceeded, interest savings or income would be calculated only for the fraction of the year that they would have been realized. If warrants are canceled or otherwise become ineffective during the year, the treasury stock method should be applied. The resulting incremental shares should be weighted by the fraction of the year during which they are outstanding. This procedure is generally not needed for warrants that lapse. This is because lapsing normally occurs only when the exercise price exceeds the market value per share. In this case, the effect of including the warrants in EPS would be anti-dilutive. Uncollected stock subscriptions are essentially the same as warrants for EPS calculations, which is because the subscriber can obtain shares by paying in the balance owed. Therefore, the unpaid balance is like the exercise price of a warrant. The accountant should treat the subscription in the same way that warrants are treated, including the application of the treasury stock method.Warrants: Definition

Warrants: Explanation

Treasury Stock Method

Example

Primary EPS

Fully Diluted EPS

The 20 percent limit

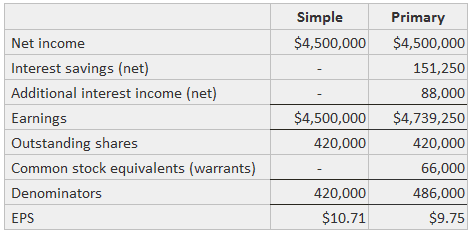

Example

Changes In Warrants

Example

Stock Subscriptions

Warrants for Earnings per Share FAQs

Warrant dilution occurs when a company gives new investors more stock than they had previously authorized. Warrants can be used to help attract investors by offering to compensate them with stock instead of cash. For example, warrant dilution could result if the company decides to raise money by issuing more shares than before.

Dilution occurs when new shares are issued. As the number of outstanding shares increases, each common shareholder's proportionate ownership interest in the company is diluted. If the total number of shares increases, then existing shareholders have to split a larger pie. If it decreases, then existing shareholders are left with more than they had before.

Calculating dilution requires an understanding of the options outstanding and how many shares have been authorized. These calculations can seem a little complicated, so it may be best to consult with a financial analyst or another expert in this area before performing them yourself. In terms of what data is needed, it is important to know the following: • number of shares outstanding • number of options exercisable • price of the options currently trading once this information has been collected, the following calculation can be applied: adjusted number of shares = (shares outstanding + number of options x shares per option) - (number of exercisable options / price of option)

Dilution has two effects. The first effect is that it reduces eps, which may depress the stock price. The second effect is that it reduces the number of shares outstanding, which helps raise the market price. Unfortunately, these effects can cancel each other out.

When a corporation issues new shares, existing shareholders will see the value of their holdings decline. If the number of outstanding shares increases by 25 percent, then each shareholder's stake in the company will decrease by this same percentage--even if they don't sell any of their shares.

True Tamplin is a published author, public speaker, CEO of UpDigital, and founder of Finance Strategists.

True is a Certified Educator in Personal Finance (CEPF®), author of The Handy Financial Ratios Guide, a member of the Society for Advancing Business Editing and Writing, contributes to his financial education site, Finance Strategists, and has spoken to various financial communities such as the CFA Institute, as well as university students like his Alma mater, Biola University, where he received a bachelor of science in business and data analytics.

To learn more about True, visit his personal website or view his author profiles on Amazon, Nasdaq and Forbes.