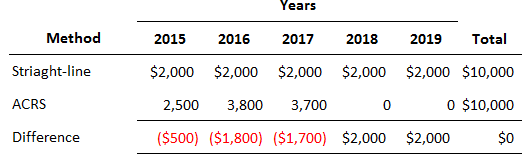

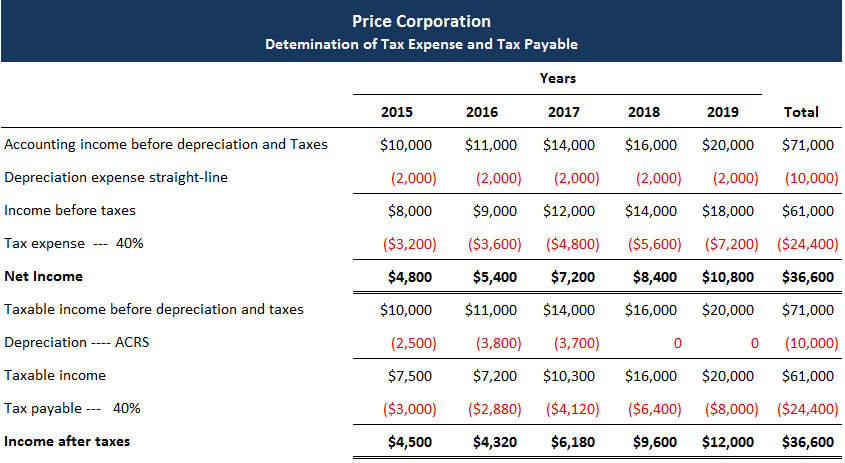

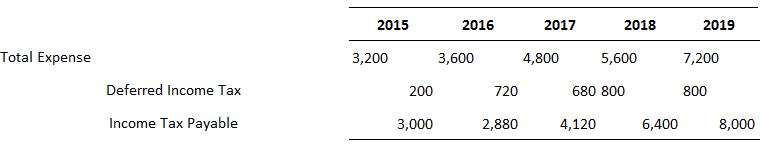

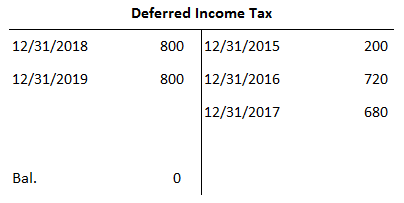

Income tax payable is a type of liability that is based on a company's taxable income. It is the amount a firm is required to pay the government in order to operate. The question to ask is: If the firm's pretax accounting income is different from its taxable income due to timing differences, what is its tax expense? That is, should it be based on the firm's pretax accounting income or on its taxable income? In the accounting profession, it feels like a company's tax expense shouldn't be based on its taxable income. Instead, the matching principle requires that the tax expense for the period is based on accounting income before taxes. To achieve this, current accounting practices require the use of interperiod income tax allocation. When a company's tax expense is based on pretax accounting income rather than on taxable income, all applicable taxes are allocated against the income for the period. This happens regardless of when the taxes are actually paid. This concept is no different from accruing a liability for wages in the current period as they are incurred, despite the fact that wages are not paid until the next period. To illustrate interperiod income tax allocation, suppose that Price Corporation uses the same accounting principles for financial reporting as it does for tax purposes, with the exception of its depreciation methods. For financial reporting purposes, the firm uses straight-line depreciation; for tax purposes, it uses ACRS. At the beginning of 2015, Price Corporation purchased a light truck. The truck has a five-year life (for accounting purposes) and falls in the three-year class life for ACRS purposes. The annual depreciation under each method is calculated as below. The calculations needed to compute tax expenses and taxes payable are shown below. The top part of the exhibit shows how the annual tax expense is calculated. Income before taxes is based on straight-line depreciation at $2,000 per year. Given a constant tax rate of 40%, income tax expense ranges from $3,200 in 2015 to $7,200 in 2019. The bottom part of the exhibit indicates how taxes payable are calculated each year. In this case, taxable income is based on ACRS depreciation. Since the truck falls into the three-year class life, all depreciation is taken in the first three years of the asset's life. Income tax payable ranges from $3,000 in 2015 to $8,000 in 2019. It is important to note that total depreciation expense, total taxes, and total net income over the five-year period are the same in both cases. This is because the total depreciation in both cases is $10,000; it is just allocated differently across the 5 years. This is typical 0f a single-asset case in which salvage values are ignored and the asset is held for its entire life. The journal entries to record the income tax expense and the related payable are: As these entries show, the expense in all periods is based on pretax accounting income, whereas the payable is based on taxable income. In 2015, the difference of $200 is a credit to the Deferred Income Tax account. At this point, the account is called a deferred tax credit. If Deferred Income Tax has a debit balance at the end of any accounting period, it is called a deferred tax charge. Similar entries are made in 2016 and 2017, both of which increase the credit balance in the Deferred Income Tax account. Since the timing difference reverses in 2018 and 2019, the Tax Payable account is greater than the Tax Expense account. Deferred Income Tax, therefore, is debited for $800 each year. In this case, the timing difference completely reverses by the end of 2019, so that by the end of that year the balance in the Deferred Income Tax account is zero. This point is shown in the following Deferred Income Tax T-account: When Deferred Income Tax has a credit balance, it is shown on the liability section of the balance as a deferred tax credit. On the other hand, if Deferred Income Tax has a debit balance, it is shown on the asset side of the balance sheet as a deferred tax charge. A related question is whether Deferred Income Tax should be shown as a current or a non-current asset liability. The Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) decided that the classification of the deferred charge or credit depends on the asset or liability that gave rise to it. Thus, if the timing difference is related to a current asset such as inventory, the resulting deferred income tax charge or credit should be classified as current. On the other hand, if the timing difference is related to a noncurrent asset such as equipment, the resulting deferred income tax charge or credit should be classified as noncurrent. Controversy still surrounds the accounting concept of interperiod income tax allocation. Academic research indicates that the use of deferred tax credits has increased over the years and, for many firms, this represents a large item in the liability section of their balance sheets. The primary reason for this is the use of the accelerated cost recovery system (ACRS) method of depreciation and, before that, the use of accelerated depreciation for tax purposes. A company with a stable/rising investment in depreciable assets using straight-line depreciation to determine pretax accounting income and ACRS to determine taxable income will likely have a growing credit balance in Deferred Income Tax. This is because the continued investment in higher-priced assets indefinitely postpones the total reversal of the timing difference, even though differences due to individual assets completely reverse. That is to say, as the effect of ACRS depreciation reverses on assets purchased earlier on, it is offset by the effect of higher-priced assets purchased in the current year. If this is the case, then the deferred tax credits may not meet the definition of a liability. Remember that a liability is defined as a probable future sacrifice of economic benefits. However, if the deferred tax credit is not reduced because the timing difference does not turn around, then the future sacrifice of cash—due to higher income taxes payable—will never take place. At the end of 2018 and 2019, Anheuser-Busch Companies had $357.7 million and $455.1 million, respectively, in its deferred income tax account. These amounts represented over 21% and 19% of total liabilities, respectively, and 30% of total stockholders' equity in both years. The deferred tax account at Anheuser-Busch has grown by over 70% since 2017. This increase is the difference between the annual tax provisions and what the company actually paid the government. In effect, between 2017 and 2020, the statutory tax rate was 46% but the effective tax rate for Anheuser-Busch (based on its actual liability) averaged only 36%. If this trend continues, then it is doubtful that the $455 million of deferred taxes shown on the liability section of the balance sheet will ever be paid.Introduction

Definition of Interperiod Tax Allocation

The purpose of interperiod income tax allocation is to allocate the income tax expense to the periods in which revenues are earned and expenses are incurred.

Example

Journal Entries to Record Income Tax Expense

Controversies Surrounding Interperiod Tax Allocation

Example

Interperiod Tax Allocation FAQs

There are two primary benefits to the use of the interperiod tax allocation. These include standardization and comparability. The use of this method ensures that all companies follow the same guidelines when calculating their deferred tax credit or liability balances. This makes it easier for analysts, investors, creditors, and other interested parties to compare the Financial Statements of different companies.

The main disadvantage associated with this method is that it requires a company to make certain assumptions about future events (specifically, expected future income taxes). These estimates can deviate from actual results and cause a deviation between the Financial Statements and actual future income tax liabilities.

The two most common methods of interperiod tax allocation are the asset approach and the liability approach. These techniques can be further divided into a balance sheet or an income statement approach.

The asset approach to interperiod tax allocation recognizes the tax effects on Fixed Assets over their useful lives. This means that these effects are recognized throughout each accounting period, which is consistent with how Fixed Assets are depreciated under gaap.

The income tax effects of an acquisition or disposition are only recognized in the period that they occur. This is because under this method all deferred taxes are eliminated prior to recognition.

True Tamplin is a published author, public speaker, CEO of UpDigital, and founder of Finance Strategists.

True is a Certified Educator in Personal Finance (CEPF®), author of The Handy Financial Ratios Guide, a member of the Society for Advancing Business Editing and Writing, contributes to his financial education site, Finance Strategists, and has spoken to various financial communities such as the CFA Institute, as well as university students like his Alma mater, Biola University, where he received a bachelor of science in business and data analytics.

To learn more about True, visit his personal website or view his author profiles on Amazon, Nasdaq and Forbes.