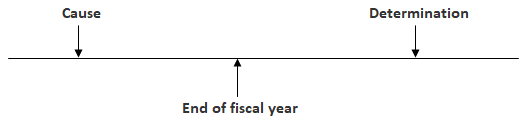

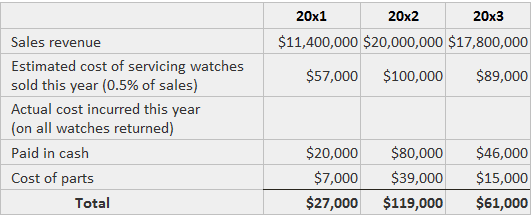

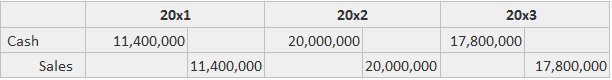

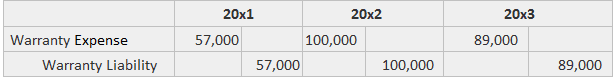

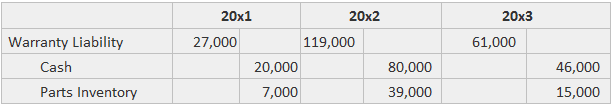

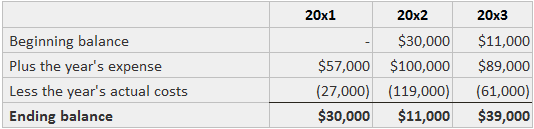

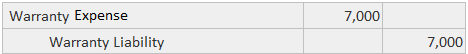

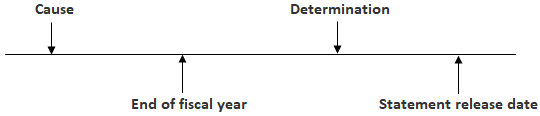

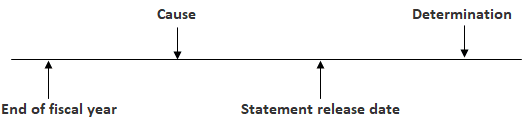

Given that liabilities involve future cash flows, they are subject to uncertainties about whether they will be paid and the amount that will be paid. In the Standard, a contingency is defined as "an existing condition involving uncertainty as to possible gain or loss to an enterprise that will ultimately be resolved when one or more future events occur or fail to occur." That is to say, there are two dates involved in a contingency: On a timeline, the sequence of these dates is as follows: If both dates fall within a fiscal year, the accountant faces no serious problem in incorporating the event and its effects in the statements. However, when the end of the fiscal year falls between the two dates (as seen below), the accounting practice becomes more difficult. The accountant is faced with projecting what will be known on the determination date and allowing for it in the statements. First, there must be an assessment of the likelihood that the determination date will reveal that there was a material effect. Second, the amount of that effect must be estimated. It should be observed that the uncertainty about effect does not relate to the cause but to the results of that event. Thus, for example, it might be known that an employee was injured in an industrial accident, but it would be uncertain as to whether the employer would be deemed responsible for payments to the employee. Alternatively, a firm might have guaranteed the debts of a subsidiary company. The agreement was the cause, but its effect is still unknown. If it is anticipated that the effect is a gain for the company, the only disclosure allowed under GAAP is a note to the statements. This type of disclosure would be provided, for example, by a company that had tentatively settled litigation. Suppose that a company anticipates settling the suit that it had filed against the XYZ Corporation for patent infringement. It is expected that the final settlement will result in cash payments of $5,000,000 in 20x1 and $2,500,000 in 20x2 and 20x3. If it is anticipated that the final effect of a contingency will be a loss, the form of the disclosure depends on the perceived likelihood of confirmation. The loss can result in the impairment of an asset (such as bad debt losses on receivables) or the creation of a liability (such as guaranteeing the loans of a subsidiary company). GAAP establishes three degrees of likelihood that the loss will be confirmed: These definitions, although subject to a high degree of subjectivity and personal judgment, exist in this form because the nature of contingencies makes it infeasible to develop more precise rules. GAAP also distinguishes those contingencies that have reasonably estimable amounts and those that do not. For example, warranty liabilities related to established products typically involve reasonably estimable amounts, but those related to newly created products may not be estimable. There are six categories of contingencies in accordance with the uncertainties about confirmation and amount. GAAP established requirements for the type of disclosure to be used for each. There are two general types of disclosures for loss contingencies: This example presents the categories in a matrix that also shows the form of disclosure. The following paragraphs discuss the general categories in more detail. Certainty of Amount When there is a high likelihood that a loss will be confirmed and the size of the loss can be estimated, compliance with GAAP requires that the loss be accrued for that amount. The objective of the requirement is to prevent the exclusion of losses and liabilities simply because the details are not yet known with certainty. A common example of a loss contingency arises out of a manufacturer's warranty agreement to repair or replace goods sold to consumers. The expense of servicing the goods is incurred in order to encourage their purchase. Consequently, compliance with sound income measurement should result in the expense being assigned to the period of the sale, even though the seller does not know with certainty either how much will be paid (if any) or to whom it will be paid. This practice must be followed if it is expected that some goods will be returned and the cost of servicing them can be estimated. Unless the items are inexpensive or not prone to malfunction, it is likely that at least some will be returned. Except when a product is newly created, the service costs can generally be estimated based on prior experience. For new products, the costs may have to be estimated from engineering studies. There are few cases in which there would be no justification for recognizing a warranty liability on the basis that the amount cannot be estimated. It should be noted that liability is recognized even though there is no actual legal claim until the consumers return the goods. The rationale for the approach lies in the need to recognize the substance of the situation over its form. The basic procedures for establishing and removing warranty liabilities are shown below for a manufacturer of electronic watches. These basic facts are known: Sales would be recorded in the normal manner: While some accountants have suggested that the sales figure should be divided as if the product and the warranty agreement were sold separately, that treatment does not seem justified unless the conditions allow them to be sold separately. The entry to record the warranty expense and the addition to the warranty liability would be based on the estimated amounts as shown below: Then, as products are returned and serviced, no additional expense is recorded. The parts and service expenditures are viewed as payments on the liability. For this example, the following summary entries would be made: The income statement for each year would disclose the expense while the balance sheet would show the liability balance. The amounts for the latter would be calculated as follows: The liability balance should be carefully monitored to determine whether it is reasonable in light of present expectations and experiences. If it is adjusted, the amount should be treated as a reduction or increase of the current year's expense. For example, if it is estimated that the balance at the end of 20x3 should be $46,000, the following adjustment should be recorded: Other situations in which probable and estimable liabilities occur are premium offers, price reduction coupons, supplemental warranty contracts, gifts certificates, and dealer rebates contingent upon meeting specified sales levels. Although each involves its own peculiar problems, the basic accounting practices are consistent with those shown above. In response to a request for clarification, the GAAP considered the treatment of probable loss contingencies when the amount can be estimated only within a range instead of a specific number. This situation constitutes a reasonably estimable loss contingency and calls for the loss to be recognized. When no particular amount within the range is thought to be more likely than any other, the firm should record the loss as the minimum figure in the range. The firm should also disclose—using a note—the possible additional loss that may have to be recognized when the determination date is reached. When there is a high likelihood that a loss will be confirmed but its amount cannot be reasonably estimated, the contingency must be disclosed in a sufficiently descriptive note. This position was adopted in order to prevent the accrual in the financial statements of amounts so uncertain as to impair the integrity of the statements. An example of a footnote describing this kind of contingency is presented below: In the event that the likelihood of confirmation of a loss is lower than probable but still reasonably possible, the firm is required to provide a note describing the situation. There is no difference in this requirement if the amount is or is not reasonably estimable. An example of a note disclosing this type of contingency follows: Apart from financial guarantees, GAAP does not require the disclosure of contingencies when there is only a remote likelihood that a loss will be confirmed on a future date. However, a disclosure can be provided if the management wants to inform the statement readers of the particular facts surrounding the situation. As an exception to its classification scheme, GAAP requires firms to disclose all material contingencies connected with their acting as a guarantor of financial obligations or other arrangements. Specific examples cited are "guarantees of indebtedness of others" and "guarantees to repurchase receivables that have been sold or otherwise assigned." An example of this kind of disclosure was provided in the annual report of Caterpillar Tractor Company: Chessie System, Inc., reported this guarantee contingency: While the requirements of GAAP are fairly clear with respect to the characteristics of contingencies that should be disclosed, practical problems can be encountered when the loss is associated with litigation. For example, if the confirmation of a loss is deemed to be probable and the company can estimate its amount, then a liability should be accrued. However, the company's management may feel that providing this kind of treatment will effectively notify the plaintiff of the defendant's willingness to settle. The disclosure of an "unasserted claim" when it appears "probable that a claim will be asserted and there is a reasonable possibility that the outcome will be unfavorable." Strict compliance with this requirement would result in the company's declaration that it had done something wrong but that no injured party had yet taken action to seek recovery. For example, a firm might have to disclose the possibility that it will be subject to legal actions after a set of complex government regulations are finally interpreted by the courts. Companies are reluctant to provide these disclosures because they may simply invite investigation or litigation. In establishing its framework for reporting contingencies, GAAP recognizes two kinds of subsequent events that can affect the type of disclosure provided. The first type encompasses the situation in which the cause of a contingency occurs prior to the end of the fiscal year and the effect is determined between the end of the fiscal year and the release date of the financial statements. This timeline shows the sequencing of the four dates: The problem arises from the fact that a contingency exists as of the statement date and is resolved prior to the publication of the statements. GAAP adopts the position that the effect (loss) and the amount should be reported as if they were known at the statement date. Thus, for example, if a litigation contingency exists as of 31 December such that a company does not know if it will win or lose, but the court rules early in January that it lost, it should report the loss as a fact. Essentially, the ruling serves as reliable evidence that the loss was probable and estimable. The second type of subsequent event considered is represented on this timeline: That is, a contingency comes into existence after the financial statement date but prior to publication. The question to be resolved is what kind of treatment should be provided if the loss confirmation is probable and the amount can be reasonably estimated. Despite the fact that the contingency meets both requirements for recognition of a loss, neither the loss nor a liability should be recognized because they did not exist as of the date of the statements. However, GAAP states that disclosures are best made by supplementing historical financial statements with pro forma financial data, giving effect to the loss as if it had occurred at the date of the financial statements. This more extensive disclosure is desirable because many financial statements users use them for forecasting. To deny them valid information about an event that affects the future of the company would be contrary to the objectives of financial accounting.Definition and Explanation

Uncertainty About Effect

Uncertainty About Amount

Disclosure Rules

Example

Reasonably estimable

Not reasonably estimable

Probable

Liability

Mandatory note

Likelihood of confirmation

Reasonably possible

Mandatory note

Mandatory note

Remote

Optional note

Optional note

Types of Contingencies

Probable and Estimable Contingencies

Range of Estimated Amounts

Probable but Not Estimable Contingencies

From time to time, Maine forests have been infested by a pest known as the spruce budworm. The budworm's larva feeds on the needles of spruce and fir trees, retarding their growth and, in many cases, killing trees if the infestation continues over several years.

In recent years, the State of Maine has conducted aerial spraying programs with the purpose of controlling the budworm ...

The kill rate in the areas sprayed averaged approximately 90%, and tree mortality was prevented in most of the sprayed areas.

The company cannot predict what damage the budworm may inflict in future years, whether or not spraying is conducted.

In order to reduce the effect of such damage, the company might change its tree-cutting patterns by cutting certain areas sooner than planned; such changes in the company's forestry management program could increase future wood costs.Reasonably Possible Contingencies

As with any manufacturer involved in operations similar to those of the company, claims may from time to time be asserted that allege liability on the part of the company connected with matters of environmental control, product liability, and general liability, including claims involving emissions from the company's cement plant and claims arising from its former aircraft manufacturing operations.

In the opinion of the company's management, it is improbable that the outcome of such litigation will be materially adverse to the company.Remote Contingencies

Financial Guarantees

On 31 December, $9.8 million of bank loans to and notes issued by Caterpillar Mitsubishi Ltd. were guaranteed by the company.

[The company] is contingently liable as a guarantor of bank loans to seven executives in the total amount of $0.6 million ... The proceeds of the loans were used for open-market purchases of the company's common stock.

Litigation Contingencies

Subsequent Events

Contingencies and Their Effects FAQs

Contingencies are conditions, situations, or events that may occur in the future and may require an adjustment to recorded assets (liabilities), revenues (expenses).

Financial statement users need to know if there is a chance of something happening that could impact their decision to invest.

Contingencies can have a variety of effects on the financial statements, depending on the type of contingency and its likelihood of occurrence. The most common effect is an increase in liabilities, which may result in a decrease in net income. In some cases, such as environmental liability, the effect may be a charge to income in the period when the contingency is incurred.

The accounting for contingencies depends on the likelihood of the event occurring and its potential financial impact. For example, if a legal dispute is considered probable and the amount in dispute can be reasonably estimated, then a liability would be recorded on the balance sheet. If the contingency is less likely to occur or the amount in dispute cannot be reasonably estimated, then no liability would be recorded.

Yes, a company can eliminate a contingency by resolving the event or occurrence that created the contingency. For example, a legal dispute may be resolved through settlement or trial. An environmental liability may be eliminated by cleaning up the pollution.

True Tamplin is a published author, public speaker, CEO of UpDigital, and founder of Finance Strategists.

True is a Certified Educator in Personal Finance (CEPF®), author of The Handy Financial Ratios Guide, a member of the Society for Advancing Business Editing and Writing, contributes to his financial education site, Finance Strategists, and has spoken to various financial communities such as the CFA Institute, as well as university students like his Alma mater, Biola University, where he received a bachelor of science in business and data analytics.

To learn more about True, visit his personal website or view his author profiles on Amazon, Nasdaq and Forbes.