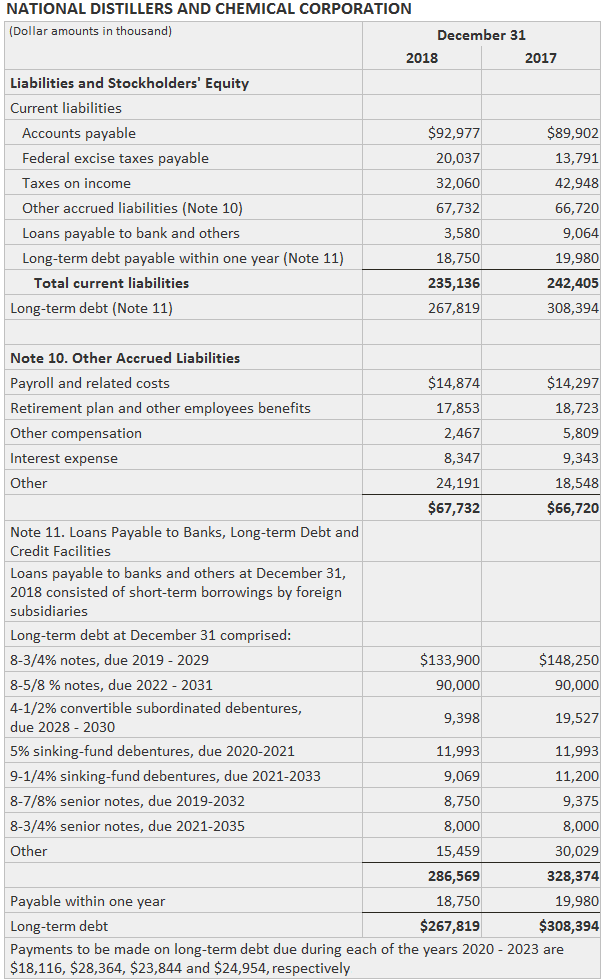

Liabilities are probable non-ownership claims against a business firm. Liabilities must arise from events that occurred in the past and are expected to be satisfied in the future. Liabilities can be held by owners if they originate through transactions in which the owners acted in the capacity of a non-owner. For example, a company will incur and report a liability that arises when cash is borrowed from an owner. In some special cases, it may be held that the claim is more like equity than a liability. This definition excludes claims that are expected to arise from events that will happen in the future. If this exclusion did not exist, it would be necessary to record all future cash outflows as liabilities. Instead, accountants recognize only claims that have come about because of past events. Liabilities originate from a variety of activities. The major origins are: Thus, some liabilities are incurred in the normal course of business as a management choice, whereas others are imposed on the firm by governmental authorities. To recognize a liability, a firm does not need to know the actual recipient of the assets that are to be transferred, or for whom the services are to be performed. For example, if General Motors guarantees or warrants an automobile, a liability must be recorded. This is despite the fact that at the time of the sale, GM does not know the specific automobile that needs repairing. For liabilities to exist, an event or transaction must already have occurred. In effect, only present—not future—obligations are liabilities. To give another example, the exchange of promises of future performance between two firms or individuals does not result in the recognition of liability or the related asset. The signing of a labor contract between a firm and an individual does not cause the firm to recognize a liability. Rather, the liability is recognized when the employees perform services for which they have not yet been compensated. In the General Motors automobile warranty case, the liability occurs at the time of sale because at that time the firm obligates itself to make certain repairs. Thus, the event has occurred and a present obligation is incurred. When reporting a liability, accountants must always ask these three questions: Answering the first question requires that the accountant determine the likelihood that the payment will be made. Because a liability influences both earning power and solvency, the answer to the question must be carefully developed and can result in either recognition of a liability on the balance sheet or a description of the situation in a note. The answer to the second question—regarding the amount to be paid—clearly impacts assessments of solvency and earning power. Information about the size of future cash flows to existing creditors helps investors and potential creditors assess the likelihood of their receiving future cash flows. The size of the liability also contributes to evaluations of management's use of leverage. The answer to the third and final question—regarding when the amount is to be paid—enables the statement user to assess separately the short-run and long-run solvency of the company. In many cases, the accountant also presents additional information about the liabilities such as the type of creditor, the reason that the liability was created, and the existence of collateral agreements. For example, these disclosures may reveal the existence of related-party transactions between the firm and its managers, major stockholders, or suppliers. Because the liability may have originated from a non-arm's-length transaction, the generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) require full disclosure concerning the party that is to be paid when a related party is involved. The identification of the type of creditor may also be helpful in allowing the statement user to determine how others (e.g., the bond market, banks, and finance companies) have assessed the solvency of the firm. Disclosures related to the liabilities of National Distillers and Chemical Corporation are illustrated below. Accounting for liabilities has been shaped mostly by common practice. Several authoritative pronouncements have been issued to bring consistency in areas where common practices were not uniform. When accounting for liabilities, the following aspects need to be considered:Liabilities: Definition

How to Recognize a Liability

Accounting Objectives

Example

Accounting Practice

Liabilities FAQs

A liability is an obligation of the business to repay the money or deliver goods or assets in return for value already received. Sometimes liabilities can be transferred, but they still represent a future obligation for the business.

An example of a liability would be a loan from a bank. The business receives cash for the loan but has to repay that amount to the bank in the future. In this case, the business has received cash value upfront and must repay it over time.

A credit card is an example of turning assets into liabilities. A customer uses the credit card to purchase an item that they do not have the cash for at that moment but will pay off in full later on. The debt incurred by the credit card is a liability because the business is obligated to repay all funds spent with interest.

Liabilities are recognized as assets that will result in a future obligation for the company. The value is placed on the balance sheet at its fair value or face value.

The accounting objectives for liabilities are to recognize the obligation incurred by the business and provide a way of measuring future repayment obligations. Liabilities also indicate how the company manages its assets and equity.

True Tamplin is a published author, public speaker, CEO of UpDigital, and founder of Finance Strategists.

True is a Certified Educator in Personal Finance (CEPF®), author of The Handy Financial Ratios Guide, a member of the Society for Advancing Business Editing and Writing, contributes to his financial education site, Finance Strategists, and has spoken to various financial communities such as the CFA Institute, as well as university students like his Alma mater, Biola University, where he received a bachelor of science in business and data analytics.

To learn more about True, visit his personal website or view his author profiles on Amazon, Nasdaq and Forbes.