When deciding how to account for an intangible asset, the first question to answer is whether there is sufficient proof that it actually exists.

The primary evidence that should be sought is documentation of either legal protection or a contract. Secondary evidence is provided by cash inflows created by the asset.

In this latter situation, judgment must be carefully exercised.

Authoritative bodies have resisted establishing rules because of the near impossibility of anticipating every situation.

Consequently, identifiable assets are more commonly recognized than goodwill.

If an intangible asset is believed to exist, the next question is what amount should be associated with it. GAAP limits this figure to historical cost.

Depending on the situation, there are several cost factors that should be considered:

- Costs paid to purchase the right or ability

- Costs to obtain basic knowledge to create an ability (research)

- Costs to obtain knowledge relating to using the ability (development)

- Costs to obtain legal protection for the right or ability

- Costs to maintain legal protection for the right or ability

Because the costs of categories 1, 4, and 5 usually involve external transactions, judgments are more easily made about them than about categories 2 and 3.

A summary is given of the relevant GAAP for these assets in the matrix in the below example. The practices vary among the four categories of intangibles:

- Purchased identifiable intangibles

- Purchased unidentifiable intangibles

- Internally generated identifiable intangibles

- Internally generated unidentifiable intangibles

Example

| Identifiable | Unidentifiable | |

| Purchased | Recognize asset Cost includes all amounts paid to obtain and protect the right or ability |

Recognize asset only when acquired with other identifiable assets Cost equals excess of total paid over fair values of identifiable assets |

| Internally generated | Recognize asset Cost includes only amounts paid to protect the right or ability |

Do not recognize asset |

Purchased Identifiable Intangibles

There are no significant accounting problems related to purchased identifiable intangible assets that are not also encountered for tangible assets.

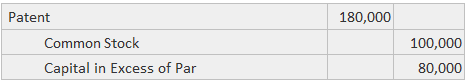

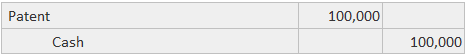

For example, if a patent is acquired by Sample Company by giving 10,000 shares of its $10 par value common stock known to be worth S18 per share, the following journal entry is:

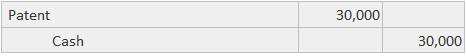

If a defense of a patent against infringement is successful, the net cost incurred should be capitalized because it will benefit future periods.

For example, if $30,000 of legal fees are incurred, the following journal entry would be made:

Purchased Unidentifiable Intangibles

Since goodwill cannot be separated from a firm, it is not possible for a buyer to acquire it without also acquiring the firm.

The cost of goodwill equals the excess of the total purchase price over the fair values of the tangible and identifiable intangible assets.

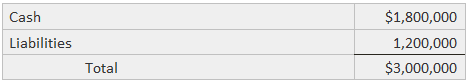

Suppose that Sample Company acquires all the assets (except cash) of XYZ Corporation by paying $1,800,000 and assuming long-term liabilities with a realistic present value of $1,200,000. Thus, the total cost is:

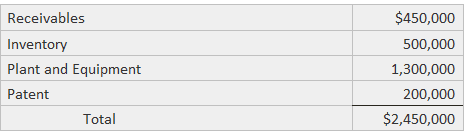

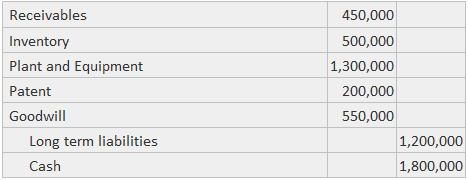

The fair values of the purchased identifiable assets were:

The cost of goodwill is $3,000,000 less $2,450,000, which equals $550,000. Sample Company would record the transaction with this journal entry:

The difference should be treated when the fair value of the identifiable assets exceeds the total cost paid.

Internally Generated Identifiable Intangibles

Accounting practices for many internally generated identifiable assets, primarily research and development (R&D), are non-uniform.

However, the following three approaches are mainly in use by today's firms:

- All expenditures are capitalized

- Some expenditures are capitalized and some are expensed

- All expenditures are expensed

The first approach is virtually certain to overstate assets and understate expenses in the current year because not all expenditures will result in future benefits.

The second approach is potentially the most useful because it assists in making comparisons of firms, but its implementation requires a set of guidelines to help the accountant judge which expenditures should be capitalized or expensed.

The third approach is virtually certain to understate assets and overstate current expenses. The reason for this is that some of the expenditures will produce useful knowledge and future benefits.

In specifying that the costs of research and development (R&D) should be expensed when incurred, the statement excludes the following:

- Materials that will be consumed in future R&D efforts

- Equipment and facilities that have "alternative future uses" (that is, they can be used for activities other than R&D)

Both items eventually appear as R&D expenses when they are consumed either directly or indirectly through depreciation.

The capitalizable costs related to R&D include the costs of obtaining patents, trademarks, or copyright protection, as well as any subsequent expenditures needed to maintain that protection.

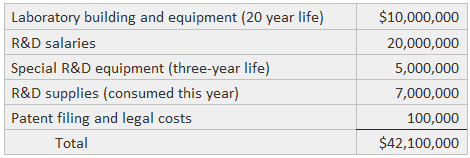

Suppose that Sample Company spent $42,100,000 during the year as follows:

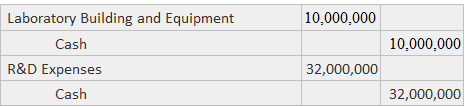

If the laboratory building and equipment have alternative future uses but the special R&D equipment does not, the entry for the acquisitions and salaries would be:

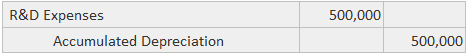

Annual depreciation on the laboratory building and equipment would be recorded as follows:

The costs of establishing the patent would be recorded this way:

This full expensing approach is not required for firms that perform R&D for other companies under contract.

Internally Generated Unidentifiable Intangibles

Since the only evidence of internally generated goodwill is an above-normal stream of earnings, accountants do not recognize it in externally presented balance sheets.

There have not been any efforts by authoritative bodies to solve the problems of specifying how to identify and measure these earnings, nor does there seem to be any widespread interest in achieving this result.

Consequently, internally generated unidentifiable intangible assets are not recognizable under GAAP.

Disclosures of Intangibles

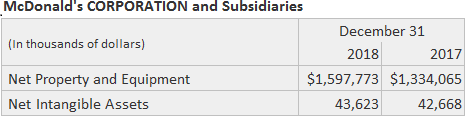

The example below shows disclosures from the balance sheet and footnote disclosures of the Joy Manufacturing Company and the McDonald's Corporation related to intangible assets.

Statement of Accounting Policies

Goodwill

Goodwill and deferred credit, which arise from business combinations that are accounted for as purchase transactions, are amortized using the straight-line method over the periods estimated to be benefited.

The amounts currently recorded are being amortized over 15-40 years.

Intangible Assets

The remaining costs of the underlying rights to the McDonald's trademarks and tradenames, acquired by the Company in 1961, amounted to on 31 December 2018 and 2017.

The company reacquired certain unlimited-term territorial franchise and operating rights. The unamortized cost of these rights amounted to and $14,701,000 on 31 December 2018 and 2017, respectively.

The company and its subsidiaries have also reacquired limited-term franchise rights in conjunction with the purchase of businesses operating McDonald's restaurants under limited-term franchise agreements.

The unamortized costs of such rights totaled $26,302,000 and $25,468,000 on 31 December 2018 and 2017, respectively.

Accounting for Acquisitions of Intangible Assets FAQs

Intangible assets are specific rights that have been purchased, created or discovered that have value to the firm. These include things like patents, copyrights, trademarks etc., which are considered assets because they provide future economic benefit. Intangibles can also consist of miscellaneous items such as donor lists, mailing lists etc.

Only those intangibles that have future economic benefit are recorded by the company. These could be rights to use certain software, franchise rights, patented processes etc. The costs of developing these intangibles along with any incidental costs are also included in the purchase price for recording purposes.

The cost of developing these intangibles along with any incidental costs are recorded as an asset. These costs are amortized over time, because it is assumed that the value of these intangibles decline as they lose their economic benefit to the company. Amortization ensures that only a portion of the cost is expensed each year, but the entire cost gets spread out over time.

Intangible assets are acquired through business combinations; for example if Company A were to buy the assets of Company B. This could be achieved either by paying cash or exchanging shares in the acquisition. However, this is not the only way intangible assets can be acquired.

These intangibles are identified through a detailed analysis by the company or an outside firm and would include things like patents, copyrights, trademarks etc., which are considered assets because they provide future economic benefit. Intangibles can also consist of miscellaneous items such as donor lists, mailing lists etc.

True Tamplin is a published author, public speaker, CEO of UpDigital, and founder of Finance Strategists.

True is a Certified Educator in Personal Finance (CEPF®), author of The Handy Financial Ratios Guide, a member of the Society for Advancing Business Editing and Writing, contributes to his financial education site, Finance Strategists, and has spoken to various financial communities such as the CFA Institute, as well as university students like his Alma mater, Biola University, where he received a bachelor of science in business and data analytics.

To learn more about True, visit his personal website or view his author profiles on Amazon, Nasdaq and Forbes.