For most operating assets, their usefulness is "consumed"—and, as such, declines—as they are applied to the production of goods or the provision of services.

This consumption is known as depreciation, depletion, or amortization. The term used depends on the type of asset in question.

The actual processes of asset consumption are dependent on a number of factors, including the type of asset, the environment, and the manner in which the firm uses the asset.

For this discussion, it is helpful to identify the three main causes of changes in an asset's utility:

- Deterioration: The decline in the physical condition of the asset while it is used directly in production or exposed to the elements.

- Obsolescence: The decline in the economic usefulness of the asset as new technology allows its output to be produced more cheaply with new assets.

- Revaluation: The change in the asset's market value as the forces of supply and demand shift; this effect is caused by factors other than deterioration and obsolescence.

Given that the amount of depreciation is usually significant in assessments of earning power and solvency, accountants need to know how to measure and report it in financial statements.

Assessment of Earning Power

The assessment of a firm's earning power is affected by depreciation accounting primarily through its impact on the firm's reported earnings.

Because an asset's life typically covers several reporting periods, accountants must determine how much depreciation to assign to each period.

To achieve this matching of depreciation expense to a time period, two fundamentally different theoretical concepts can be applied: the allocated cost concept and the value concept.

Under the allocated cost concept, the amount of depreciation reported for a given period equals a computed fraction of the asset's cost.

This approach attempts to anticipate deterioration and obsolescence but ignores changes through revaluation at the time that they occur. Consequently, only the expense is reported until the time of the asset's disposal.

Then, if it is sold, a gain or a loss may occur when the proceeds of the sale differ from the unallocated portion of the asset's cost.

In contrast to the allocated cost concept, the value concept considers not only deterioration and obsolescence but also revaluation resulting from supply and demand shifts.

In applying this concept, it is necessary to determine the change in an asset's value over the reporting period.

If the value declines, depreciation expense is reported. If the value increases, a holding gain is reported.

When the asset is sold, the change in value since the prior balance sheet date is reported as depreciation or a holding gain, and there is no gain or loss. from the disposal.

It is worth pointing out that this approach's reliance on non-transactional data has prevented it from being generally accepted.

It should also be observed that both approaches produce identical amounts of total income for the entire period that the asset is owned, even though a substantial difference is likely between the amounts reported as expenses in any particular year.

Example

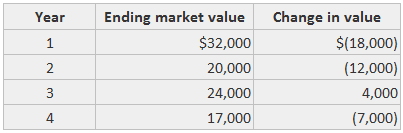

Suppose that Sample Company acquired an asset at the beginning of year 1 for $50,000. Its market value at the end of the next four years and the change in value in each year are as follows:

The tables below show the income that would be reported if the asset produced $60,000 revenue each year and was sold for $17,000 at the end of its life.

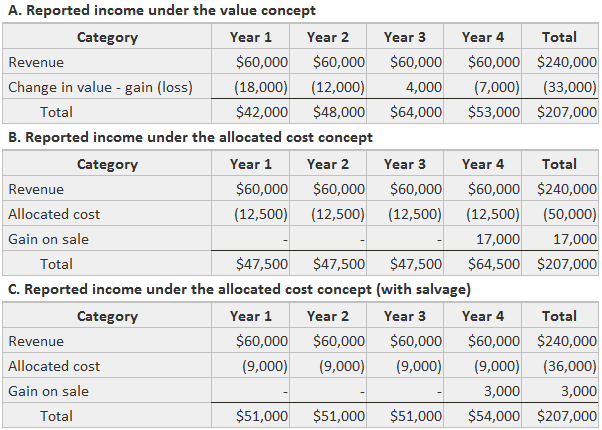

Notice that the total income is $207,000 for the four-year period.

In the above image, Table B shows the calculation of income when the original cost is allocated over the 4-year life at $12,500 per year.

The asset is sold at the end of year 4 for $17,000, which results in a gain of the same amount because the asset has a book value of zero.

Notice that the total income is also $207,000, but that there is less variation in the annual reported income figures.

Further, observe that the fourth year shows a large adjustment for the fact that using the asset did not consume all of the asset's value.

The generally applied allocation approach assigns to expense only the amount of expected decrease in the value of the asset that is anticipated because of use.

Table C in the above image shows the income that would be reported if the expected salvage value at the end of the fourth year is $14,000. The $36,000 net cost is allocated at $9,000 per year.

Because the actual disposal price is $17,000, a return on the sale of $3,000 is reported.

Notice that total income over the asset's life is again $207,000 and the use of the salvage value results in less variability in the reported income figures.

The use of the salvage value also causes the depreciation expense in each year to come closer to the average annual decline in value.

In essence, a better approximation of the annual expense was achieved by using a reasonable salvage value.

It is worth noting the consistency of the allocated cost concept with historical cost theory used in general practice, as well as the potential for subjectivity and other factors of unreliability inherent under the value concept.

For these reasons, GAAP for depreciation are based on allocations of the original cost. The discussion in the accounting practice section of this article explains the procedures and alternate methods used.

Depreciation and Return on Assets

Insight into a firm's earning power is offered by comparing earnings with the resources used to achieve those earnings.

As the rate of return ratio increases, this indicates that the company's management is more efficient in using its resources.

Also, firms with higher rates of return tend to have greater earning power compared to companies with lower ratios, especially if they are operating in a similar industry.

Accountants have found that this ratio is difficult to provide for investors due to the lack of agreement about which amount to use when describing the committed resources.

For example, the following alternatives have been proposed: full original cost, residual book value, current cost to replace, and current disposal value.

Further, the choice of the asset value has implications for the measurement of earnings in the numerator.

Assessments of Solvency

Three items of information about the use and disposal of operating assets help statement users assess a firm's solvency.

- First, the amount of funds generated from operations describes the firm's ability to meet its cash needs from its primary activity.

While the indirect approach to computing funds from operations shows depreciation as an addition to net income, depreciation is clearly not a source of funds.

It is especially important to recognize that there is no relationship between depreciation, which is merely the allocation of an asset's historical cost to an accounting period, and the accumulation of funds for replacing a firm's assets.

- The second item of information is the amount of funds actually provided from the disposal of existing assets.

Because disposals are non-routine, disclosure of their results helps the statement reader assess how much of the firm's funds were generated by unusual sources.

Adjusting net income to remove gains and losses gives a better description of the proportion of funds provided by these transactions.

- Third, some idea of the amount of cash that would be available to the firm if it sold its existing assets might be viewed as helpful for assessing the firm's ability to meet its payment commitments.

However, even this approach to valuation is unlikely to help unless the firm intends to liquidate its operating assets.

Accounting Practice

The application of the net cost allocation approach under GAAP requires that three factors be established about an asset at the time it is put into service. These factors are:

- Service life: The time period for which the asset's usefulness is expected to be consumed.

- Depreciable basis: The value of the usefulness that is expected to be consumed.

- Depreciation method: The pattern in which the usefulness is expected to be consumed.

Accounting Objectives for the Use and Disposal of Operating Assets FAQs

If you are using residual value accounting then you would not record depreciation expense. If you are using full-cost accounting then you would record depreciation expense as a function of the original cost.

Depreciable basis is determined by determining how much used will be consumed from the asset, and the disposal value helps determine how much will be consumed.

When an asset's depreciation period begins to expire, depreciation starts. If it is not expiring at all, then no depreciation will be recorded. Depreciation expense decreases current period net income and increases accumulated depreciation.

No, assets may be disposed of before they are fully consumed, but always before their useful life expires.

If you use residual value accounting then you would not use net cash flows from operating activities, but if you use full-cost accounting then you would.

True Tamplin is a published author, public speaker, CEO of UpDigital, and founder of Finance Strategists.

True is a Certified Educator in Personal Finance (CEPF®), author of The Handy Financial Ratios Guide, a member of the Society for Advancing Business Editing and Writing, contributes to his financial education site, Finance Strategists, and has spoken to various financial communities such as the CFA Institute, as well as university students like his Alma mater, Biola University, where he received a bachelor of science in business and data analytics.

To learn more about True, visit his personal website or view his author profiles on Amazon, Nasdaq and Forbes.