Although some accountants argue that exchanges of similar assets should be treated the same as exchanges of dissimilar ones, the generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) treat these transactions as being substantively different.

That is to say, the exchange is viewed as a restructuring of the firm's productive capacity rather than a disposal and acquisition.

Consequently, the GAAP prescribe a treatment for these exchanges that differs from the one used for dissimilar assets.

For exchanges of similar assets, the cost of the new asset should be based on the book or fair value of the old asset, whichever value is lower.

Exchanges of Similar Nonmonetary Operating Assets Without Cash

If cash is not involved, the cost of the new asset is either the book value or the fair value of the old one, whichever is lower.

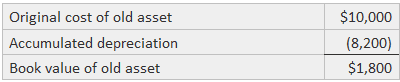

For example, consider the following information about an old asset that has been exchanged for a new one:

The following sets of entries are recorded for two different fair values of the old asset:

Thus, only losses can be recognized on exchanges of similar operating assets when no cash is involved.

If the fair value of the new asset is known with more certainty than the fair value of the old asset, the cost of the new asset is either the fair value or the book value of the old asset, whichever is lower.

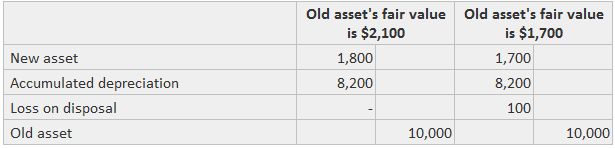

Exchanges With Cash Given

If cash is given by the buyer, the cost of the new asset is the sum of the cash paid and the lower of the old asset's fair or book value.

For the above example, these entries would be recorded if the buyer were to give $5,000 cash in addition to the old asset:

If the fair value of the new asset is known more reliably, then the cost of the new asset is either the fair value or the sum of the cash paid plus the book value of the old asset, whichever is lower.

Exchanges With Cash Received

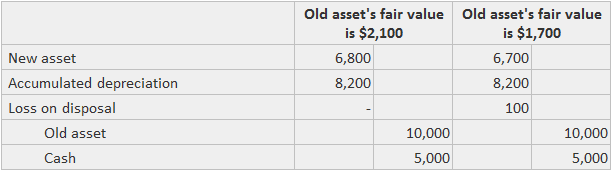

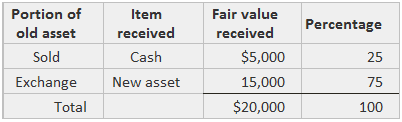

When an old asset is given up in exchange for a new similar asset and cash, the viewpoint of the GAAP is that part of the firm's productive capacity is sold and part of it is restructured.

This interpretation is consistent with the underlying theory described earlier. Implementing it creates the need for allocating the book value of the old asset into the part that is sold and the part that is exchanged.

The allocation is done on the basis of the proportional relationship between the fair value of the new asset and the cash received.

Example

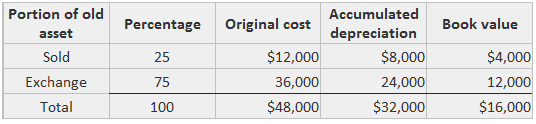

For example, assume that an old asset is exchanged for $5,000 cash and a new asset worth $15,000. These calculations would determine which fraction of the old asset was sold and which was traded:

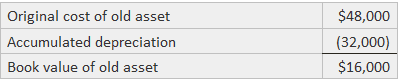

Then, these percentages would be used to determine the book value of the sold and exchanged. Assume these facts about the old asset:

The following calculations are made:

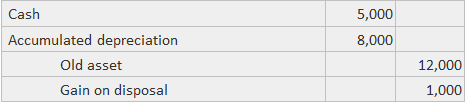

Thus, the entry for the portion sold would be:

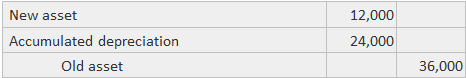

The cost of the new asset is equal to the book value of the exchanged portion of the old asset. The entry would be:

In practice, the two entries are combined:

If the book value of the old asset is greater than the sum of the cash received and the fair value of the new asset, the firm records a loss equal to the difference, and the book value does not need to be partitioned into the sold and traded portions.

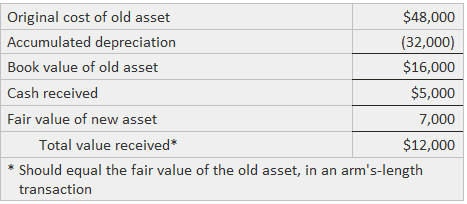

Suppose the following facts about two assets:

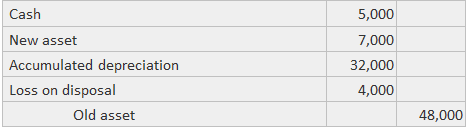

In this case, the total loss on disposal is $4,000 (i.e., $16,000 less $12,000). The transaction would be recorded with the following journal entry:

Exchange of Similar Nonmonetary Operating Assets FAQs

An asset being replaced is replacing a similar or dissimilar asset. An asset being disposed of is disposing of either a similar or dissimilar asset.

Exchanges with cash received are treated as simultaneous transactions, where the new asset is recorded at its fair market value. Exchanges with cash given are not simultaneous transactions; the old asset is replaced by a new one and is accounted for at the cost of the replacement (the sum of cash paid plus lower of book or fair value of old asset).

Asset acquisitions are similar to exchanges with cash received in that the new asset is recorded at fair market value. Exchanges of assets would be accounted for as if two separate transactions had taken place, with one asset acquired and another disposed. However, when inputs from both transactions are used to create an asset of higher value, it must be accounted for as a replacement of the old asset and its book value is allocated accordingly.

It depends on whether the assets have a similar fair value and useful lives. In some cases, where the group of assets is expected to sell at about the same time or when they are dissimilar in nature, it may be appropriate to account for them as simultaneous transactions.

Exchanges of assets and asset acquisitions are treated differently. Asset acquisitions result in a new asset at cost (the sum of cash paid plus the fair market value of the old asset). Exchanges of assets require that an existing asset be replaced, and it is accounted for as if two separate transactions had occurred. The book value of the old asset is allocated between the sold portion of the old asset and exchanged portion of the new one.

True Tamplin is a published author, public speaker, CEO of UpDigital, and founder of Finance Strategists.

True is a Certified Educator in Personal Finance (CEPF®), author of The Handy Financial Ratios Guide, a member of the Society for Advancing Business Editing and Writing, contributes to his financial education site, Finance Strategists, and has spoken to various financial communities such as the CFA Institute, as well as university students like his Alma mater, Biola University, where he received a bachelor of science in business and data analytics.

To learn more about True, visit his personal website or view his author profiles on Amazon, Nasdaq and Forbes.