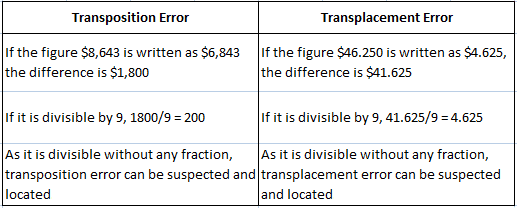

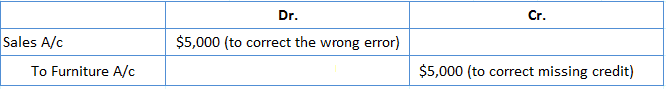

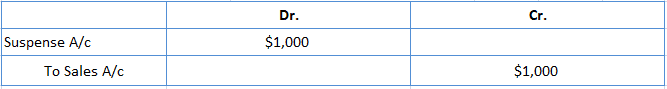

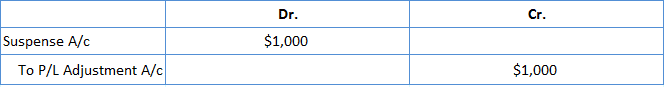

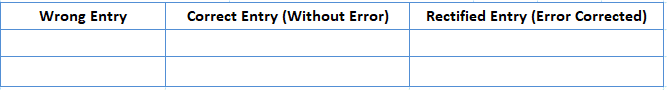

In accounting, errors are the mistakes that the bookkeeper or accountant makes. These mistakes may occur in any of the following situations, among others: The process of finding and correcting mistakes of this kind is called rectification of errors. Rectification of errors can be addressed by answering the questions of what, why, and how. To prove the arithmetical accuracy of accounting, the trial balance is prepared (either under the total method or under the balance method) to confirm that the debits are equal to the credits. Despite the best efforts of the bookkeeper or accountant and the agreement of the trial balance, errors may still continue to prevail. If such errors are left uncorrected, they affect the final accounts of the concern. Therefore, there is a need for rectification. Errors can be classified broadly into two types: intentional errors and unintentional errors. Intentional errors are generally strategic in nature. Such errors are committed at the management level and not at the clerical level. For example, stock may be recorded at market price, which is higher than the cost price, to increase the current ratio and to create confidence among creditors. This is done knowing that stock should be recorded in the books at cost or market price, whichever is less. Sometimes, the balance sheet of the company is window-dressed to paint a picture that is rosier than reality to the shareholders and the public. Such intentional errors attract legal remedies rather than rectification. Therefore, intentional errors are excluded from this article’s discussion of how errors should be rectified. Our prime focus is on unintentional errors, which occur at the clerical level during the normal course of recording, classifying, posting, casting, and so on. Unintentional errors are a category of mistakes that need to be rectified to maintain accounts correctly (i.e., to ensure they are true and fair). Therefore, in this article, whenever we refer to rectification of errors, we mean unintentional errors. Unintentional errors are classified based on the following: Hence, unintentional errors are classified on many bases. One of the classifications is on the basis of disclosed errors and undisclosed errors. This classification is intended to demonstrate that the trial balance is not the absolute proof of the accuracy of ledger accounts, although it proves arithmetical accuracy. A trial balance can disclose the following errors: However, a trial balance cannot disclose errors of principle, errors of omission, posting to the wrong account, the wrong entry of the amount in the original books, and compensating errors. Another classification of errors is based on how errors affect accounts. This classification system is as follows: A final popular classification system for errors is based on their nature. The types of errors identified under this system are the following: Locating errors is like searching for a black cat in a dark room, all the while wearing sunglasses. However, there are some methods that can make it easier to locate errors. A trial balance is prepared to check arithmetical accuracy. Hence, the task of locating errors should start from the trial balance. Earlier, it was mentioned that some errors are disclosed by the trial balance, while others are not. If the trial balance is in disagreement, then it is an indication that errors exist in the books of accounts. The steps mentioned here, if meticulously followed, will help to locate unintentional errors: Begin by checking the totals of the trial balance once again. For example, if the debit total is not equal to the credit total (or vice versa), find out the difference between the debit and credit totals, divide that difference by 2, and see whether such an amount appears in the trial balance. If a similar figure exists, check whether it is entered in the correct column. Also, if a figure is entered in the wrong column, then there will be a difference to the extent of double the amount. We cannot rule out the possibility of errors still existing due to the transposition or transplacement of figures. To locate these errors, divide the difference by 9. If the difference divides evenly into 9, there is a chance that errors exist due to transposition or transplacement. Transposition indicates that the individual figures in an item are interchanged, whereas in transplacement, the digit is either moved forward or backward to cause the error. For example, see the following tabular representation. If there are still errors after checking the journal, ledger, subsidiary books, and trial balance totals, then transfer the difference to a temporary account (called a suspense account). Enter that amount in the trial balance, tally the trial balance, and prepare the final accounts. When the error is located, corrections can be applied by giving the necessary debit or credit to the erroneous account and making the opposite entry in the suspense account. Thus, the suspense account is closed after being temporarily created. Errors should be rectified; otherwise, a business enterprise will not be transparent. It will fail to be creditworthy and not show the correct profit or loss. In other words, it will not show the true picture. So, errors should be rectified; but are there other reasons for doing so? Every business is interested in finding out its true results in terms of profit or loss from the operational activities, as well as its true financial position at the end of the financial year. Personnel in the accounts department will try to maintain the firm’s accounts accurately, ensuring that the true profits or losses are determined and, furthermore, that the statement of affairs paints a correct picture. On the basis of the principle that prevention is better than the cure, the early detection of errors is needed to help businesses be transparent, creditworthy, and show the correct profit or loss, thereby painting an accurate picture of their financial position. In other words, the rectification of errors is essential to ensure: Suppose that errors are left uncorrected. These errors will influence the profit and loss account and balance sheet. Although the trial balance is prepared to evaluate accuracy, it does not disclose every type of error. Furthermore, it is possible that the trial balance was made to agree by entering the suspense account balance. In any case, if the errors are not rectified, they will have an adverse effect on the firm’s position in terms of profits or losses and assets or liabilities. Therefore, they must be rectified. Such rectification may be carried out with the help of the following steps: Across the pre-trial balance, post-trial balance, and pre-final accounts stages, rectification is carried out by modifying entries either directly or through a suspense account. For the post-final accounts stage, rectification is carried out through profit and loss account adjustments. To ensure confidence in the entries made in the books of account, corrections are not undertaken by striking off figures, erasing figures, or rewriting them. Even overwriting is not allowed. Instead, corrections are applied by following a standard methodology. The permitted methodology involves correcting any errors through rectifying entries. In the books of account, the following are not allowed: Generally, rectification is carried out through the journal proper. 1. If the errors are located before the preparation of the trial balance, corrections can be carried out directly by means of a rectifying entry, which may be a single corrective entry or a rectifying journal entry. Whether a rectifying journal entry should be passed or not depends on the nature of the mistake. For example, a company’s sales book is undercast by $1,000. This can be corrected by crediting the sales account directly with $1,000. No rectifying journal entry is required. Suppose the sale of old furniture for $5,000 is credited to the sales account. This error cannot be corrected directly by crediting the furniture account with $5,000. Instead, a rectifying journal entry is required to apply the correction to both the sales account and the furniture account. Thus, the rectifying journal entry will be as follows: 2. If the errors are located after the preparation of the trial balance (post-trial balance stage) with the suspense account, then all the corrections are carried out through rectifying journal entries only. As it is necessary to close the suspense account, the other aspect of debit or credit of the rectification will affect the suspense account. In the previous example, where the sales book is undercast by $1,000, the correction is carried out by passing a rectifying journal entry as follows: Here, after the sales account has been given a proper credit entry, the suspense account receives a debit as rectification. 3. If the errors are located after the preparation of the final accounts, they will already have impacted the profit or loss of the business. Hence, the rectification should be carried out using a profit and loss adjustment account. The above example of a sales book being undercast is corrected with a rectifying entry as follows: Given that the sales figure increases the profit, it is necessary to credit the profit and loss adjustment account to rectify this mistake. By debiting the same amount to a suspense account, the balance of the suspense account is reduced to that extent. For the purpose of establishing a clear understanding of the methodology used to rectify errors, the following format may be followed: 1. See what is actually done in the books (i.e., determine the error committed) 2. Correctly analyze what should have been done (i.e., find the correct entry that should have been passed) 3. See what correction is needed (i.e., the rectified entry that is recorded by comparing the entries in (1) and (2)). See the following tabular representation.Rectification of Errors: Definition

Accounting errors occur when, in the accounting period, the basic principle is violated that every debit should have an equal credit.

A core principle of accounting is that every debit should have an equal credit. If this basic principle is violated in any manner, at any time, or at any stage during the accounting period, errors (i.e., mistakes) occur.Classification of Errors

Intentional Errors

Unintentional Errors

Classification of Unintentional Errors

How to Locate Errors

Steps to Locate Errors

The Need for Rectification of Errors

1. Before the trial balance is prepared (pre-trial balance stage)

2. After the trial balance is prepared with or without the suspense account (pre-final accounts stage)

3. After the final accounts are prepared (post-final accounts stage)How Are Errors Rectified?

Rectification of Errors Through Journal Proper

Error Rectification Methodology

Rectification of Errors FAQs

The process of finding and correcting mistakes of this kind is called Rectification of Errors. Rectification of Errors can be addressed by answering the questions of what, why, and how.

In accounting, errors are the mistakes that the bookkeeper or accountant makes. These mistakes may occur in any of the following situations, among others:- classifying accounts- writing subsidiary books- posting entries to ledger accounts- casting totals- balancing accounts- carrying balances forward.

Errors can be classified broadly into two types: 1. Intentional errors: these are generally strategic in nature. Such errors are committed at the management level and not at the clerical level.2. Unintentional errors: this type of error is a category of mistakes that need to be rectified to maintain accounts correctly.

Errors should be rectified; otherwise, a business enterprise will not be transparent. It will fail to be creditworthy and not show the correct profit or loss. In other words, it will not show the true picture.

To ensure confidence in the entries made in the books of account, corrections are not undertaken by striking off figures, erasing figures, or rewriting them. Even overwriting is not allowed. Instead, corrections are applied by following a standard methodology. The permitted methodology involves correcting any errors through rectifying entries.

True Tamplin is a published author, public speaker, CEO of UpDigital, and founder of Finance Strategists.

True is a Certified Educator in Personal Finance (CEPF®), author of The Handy Financial Ratios Guide, a member of the Society for Advancing Business Editing and Writing, contributes to his financial education site, Finance Strategists, and has spoken to various financial communities such as the CFA Institute, as well as university students like his Alma mater, Biola University, where he received a bachelor of science in business and data analytics.

To learn more about True, visit his personal website or view his author profiles on Amazon, Nasdaq and Forbes.