Bank account garnishment is a legal process that allows creditors to collect directly from a debtor's bank account. It typically arises when a debtor defaults on a debt and the creditor obtains a court judgment affirming the debt. The creditor then receives a garnishment order, which instructs the debtor's bank to freeze and transfer funds to settle the debt. Various debts, such as credit card bills, student loans, tax debts, and child support, can lead to garnishment. However, specific laws protect debtors by limiting the garnishment amount, providing exemptions for certain income types, and enabling challenges to the garnishment process. Despite these protections, bank account garnishment can significantly impact a debtor's personal finances, emphasizing the need for sound financial management. The bank account garnishment process usually begins with a debtor defaulting on a loan or debt. Creditors may then take legal action to obtain a judgment against the debtor. Once they secure this judgment, they can apply for a garnishment order. This order gives them the legal right to directly seize funds from the debtor's bank account. Debts may originate from multiple sources such as student loans, credit card bills, mortgages, or even medical bills. Failure to repay these debts in a timely manner could put the debtor at risk of garnishment. Before a creditor can garnish a bank account, they must first obtain a judgment from the court, proving the debtor owes the debt. This usually follows a lawsuit filed by the creditor against the debtor. Once a court judgment is in place, the creditor may seek a garnishment order. This order is served to the debtor's bank, instructing them to freeze and subsequently release funds to the creditor. The debtor is the individual or entity that owes the debt. In the context of bank account garnishment, the debtor is at risk of having their bank account frozen and funds seized. The creditor is the individual or entity to whom the debt is owed. They initiate the garnishment process by first securing a court judgment and then a garnishment order. The bank or financial institution is where the debtor's money is stored. It is responsible for enforcing the garnishment order by freezing and transferring funds from the debtor's account to the creditor. The court acts as an arbitrator, establishing the validity of the debt claim and issuing the garnishment order. The court's decision determines whether a creditor can proceed with garnishment. Credit cards, personal loans, and payday loans can result in garnishment if left unpaid. Federal and private student loans are also eligible for garnishment, but the processes vary slightly. Notably, federal student loans can garnish wages without a court order. Unpaid taxes, both at the federal and state levels, can result in bank account garnishment. The IRS typically takes this step when other debt recovery methods fail. Failure to pay child support or alimony can also lead to garnishment. In some cases, these debts allow for more aggressive garnishment, with a higher percentage of the debtor's funds seized. Debtors retain specific rights during the garnishment process. Debtors have the right to be notified at different stages of the garnishment process. This includes notice of the lawsuit, the judgment, and the garnishment order. Debtors can challenge the garnishment in court. This could involve disputing the validity of the debt, the judgment, or the garnishment process. Certain types of income, such as social security benefits, disability benefits, and veterans' benefits, may be exempt from garnishment. Despite the aggressive nature of garnishment, protections are in place at both federal and state levels. In certain situations, declaring bankruptcy may offer some respite. At the federal level, several laws limit the extent and nature of garnishment. For example, the Consumer Credit Protection Act caps the amount that can be garnished from a person's income. States often have their own laws providing additional protections for debtors, such as further restrictions on the amount garnished or protections for specific types of income. In some cases, declaring bankruptcy can provide protection against garnishment. Both Chapter 7 and Chapter 13 bankruptcy can lead to an automatic stay, preventing creditors from collecting debts. In the short term, garnishment can lead to financial hardship, as it reduces available funds for daily living expenses. Long-term effects may include difficulty securing future credit, a cycle of debt, and potential problems with securing housing or employment due to a tarnished financial record. Garnishment can significantly lower a credit score. Coupled with the preceding judgment, this can severely impact a debtor's ability to secure credit in the future. Open communication and negotiation with creditors can sometimes prevent garnishment. Many creditors prefer to arrange a payment plan rather than go through the cost and time involved in a lawsuit. Proactively managing debts, possibly through consolidation, can prevent the escalation of debt situations to the point of garnishment. Engaging a lawyer can help navigate the legal landscape of garnishment, contest the debt or garnishment, and explore possible defenses. Bank account garnishment, a legal method allowing creditors to collect from a debtor's bank account, usually ensues when debts remain unpaid. It involves various parties, including debtors, creditors, banks, and courts. Many debt types can instigate garnishment, like consumer debts, student loans, tax debts, and child support. Despite the debtor's rights and federal and state protections, garnishment significantly impacts personal finances, underscoring the necessity of financial management. Proactive measures like negotiation with creditors, debt management, consolidation, and seeking legal assistance can help avoid or lessen garnishment's effects. It's essential to understand this process to navigate the complex financial and legal landscapes adeptly and safeguard one's financial health.Bank Account Garnishment: Overview

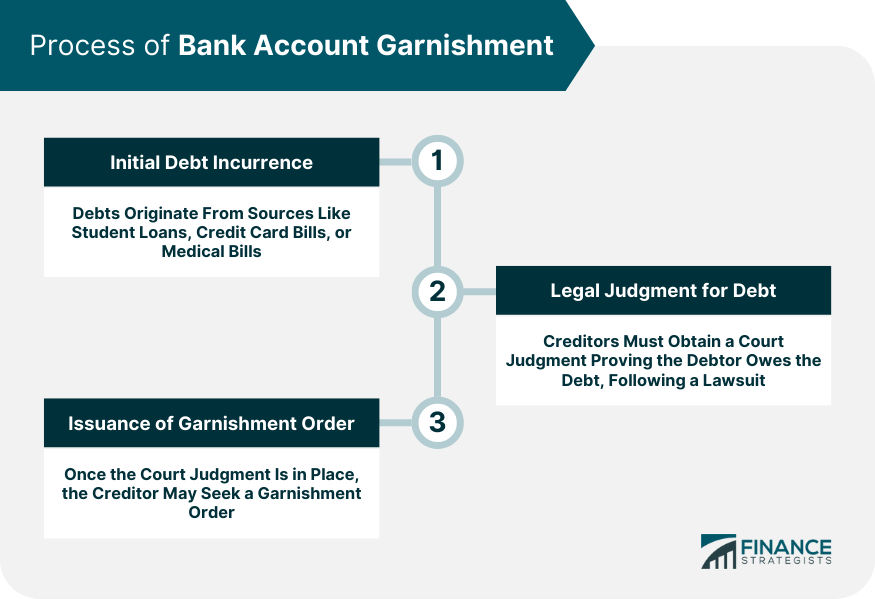

Process of Bank Account Garnishment

Initial Debt Incurrence

Legal Judgment for Debt

Issuance of Garnishment Order

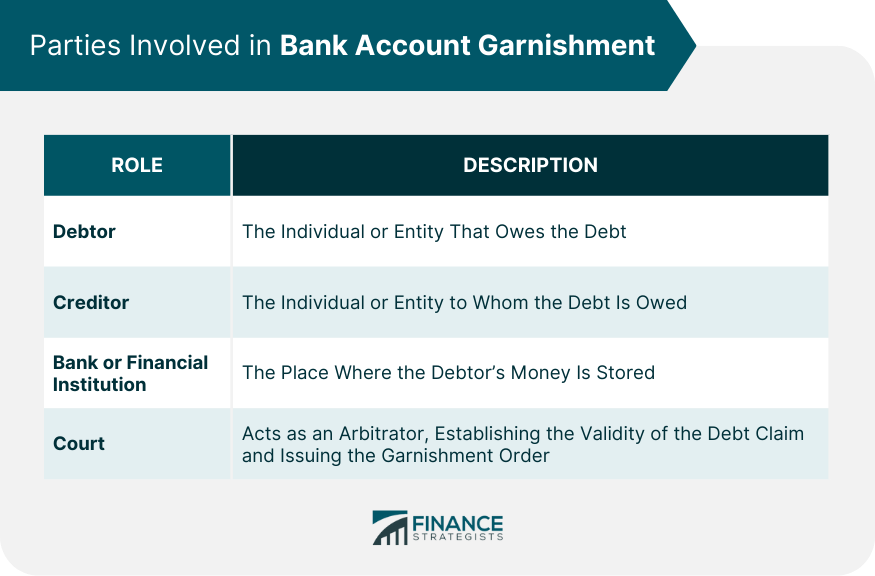

Parties Involved in Bank Account Garnishment

Debtor

Creditor

Bank or Financial Institution

Role of the Courts

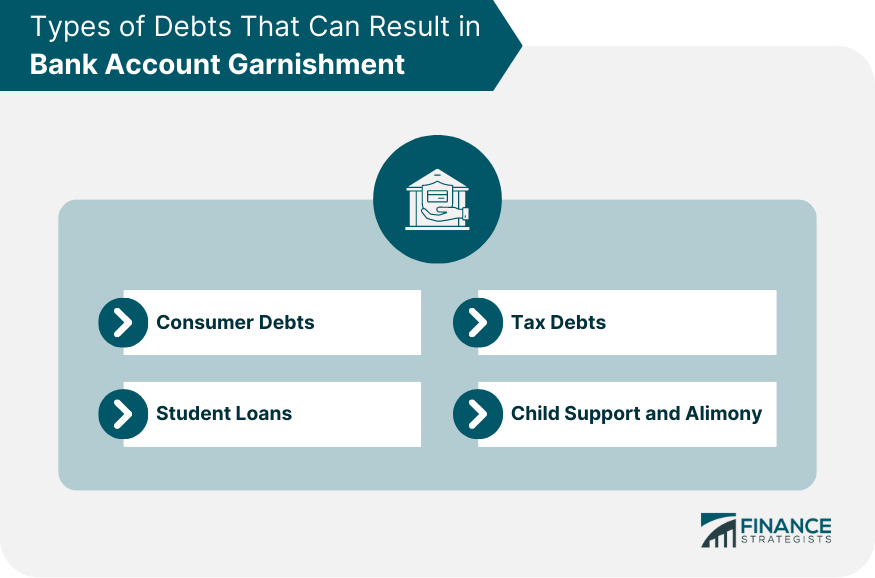

Types of Debts That Can Result in Bank Account Garnishment

Consumer Debts

Student Loans

Tax Debts

Child Support and Alimony

Rights of the Debtor during Bank Account Garnishment

Right to be Notified

Right to Contest the Garnishment

Right to Exempt Certain Funds

Protection From Bank Account Garnishment

Federal Protections

State Protections

Bankruptcy as a Protection Method

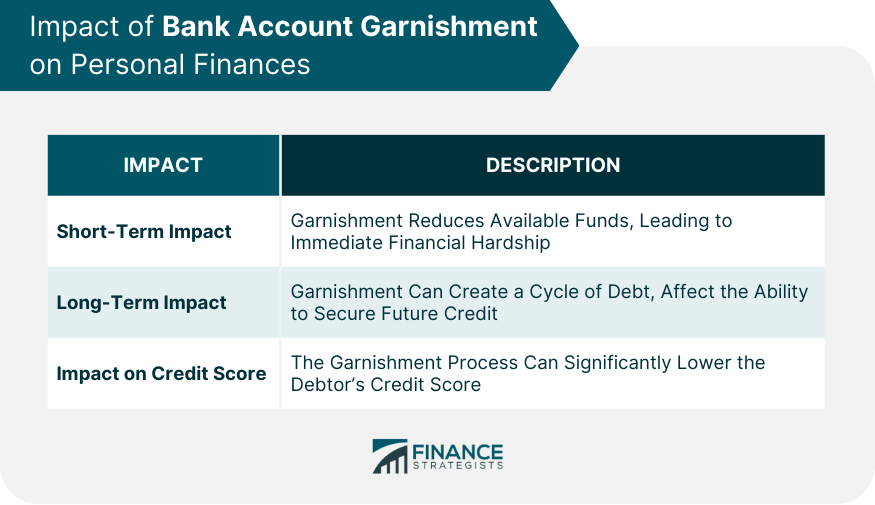

Impact of Bank Account Garnishment on Personal Finances

Short-Term Impact

Long-Term Impact

Impact on Credit Score

Strategies to Prevent Bank Account Garnishment

Negotiation With Creditors

Debt Management and Consolidation

Legal Assistance

Conclusion

Bank Account Garnishment FAQs

When a garnishment order is issued, your bank is legally obliged to freeze your account and evaluate your balance. The funds up to the amount specified in the garnishment order will then be transferred to your creditor.

You can protect your bank account balance by negotiating with your creditors, proactively managing your debts, consolidating your loans, or seeking legal assistance. Certain types of income are also exempt from garnishment, which can protect a portion of your balance.

Various types of debts can lead to garnishment, including consumer debts, student loans, tax debts, and child support. If these debts are left unpaid, your creditor can obtain a court order to garnish your bank account balance.

Yes, bank account garnishment can significantly impact your credit score and bank account balance. The garnishment reduces your available funds and, along with the preceding judgment, can severely lower your credit score.

Yes, in certain situations, declaring bankruptcy can provide protection against garnishment. Both Chapter 7 and Chapter 13 bankruptcy can lead to an automatic stay, preventing creditors from collecting debts and protecting your bank account balance.

True Tamplin is a published author, public speaker, CEO of UpDigital, and founder of Finance Strategists.

True is a Certified Educator in Personal Finance (CEPF®), author of The Handy Financial Ratios Guide, a member of the Society for Advancing Business Editing and Writing, contributes to his financial education site, Finance Strategists, and has spoken to various financial communities such as the CFA Institute, as well as university students like his Alma mater, Biola University, where he received a bachelor of science in business and data analytics.

To learn more about True, visit his personal website or view his author profiles on Amazon, Nasdaq and Forbes.