A will is a legal document that outlines how a person wishes their assets, also known as their "estate," to be distributed after their death. It can detail a variety of arrangements, including who will receive the assets, what proportions will be allotted, and even how certain assets should be handled or managed. Probate is the judicial process whereby a deceased person's will is "proved" in a court of law and accepted as a valid public document. This process is meant to ensure the will is authentic and can effectively administer the deceased's estate. Probate also handles any disputes surrounding the will, including any contestations. Typically, a will is contested before or during the probate process. In some cases, a will can be contested after the probate process has been completed, although this is generally more difficult. Various factors determine whether a will can be contested post-probate, such as jurisdictional rules, legal grounds for contestation, and the timing of the contestation. This means that the deceased did not fully understand the nature and consequences of their actions when they made the will. Evidence such as medical records or witness testimonies may be used to prove this ground. This essentially implies that the testator was forced, pressured, or manipulated into drafting their will in a certain way. Proving undue influence can be challenging, as it needs strong evidence that demonstrates the deceased was under an undue amount of pressure or control from another party at the time the will was created. This would suggest that the will was either not crafted by the deceased or was altered without their knowledge or consent. For instance, if the deceased's signature was forged, or if the contents of the will were fraudulently manipulated, these circumstances could provide a solid basis for contestation. If a will does not comply with the requisite legal formalities during its creation, it could be contested. These formalities might include aspects such as the necessary number of witnesses during the signing or whether the will was properly documented and authenticated. Many jurisdictions impose specific time limits within which a will must be contested following the probate process. For instance, some jurisdictions may allow a one-year time limit from the date of probate. If the time limit expires, the ability to contest the will might be lost. Thus, swift action is necessary when grounds for contestation are identified. It's also important to note that these time limits can vary significantly from one jurisdiction to another. In legal terms, only an "interested party" can contest a will. An interested party typically refers to those who stand to benefit or lose from the will's provisions or lack thereof. People who can potentially qualify as interested parties include spouses, children, heirs, devisees, creditors, and others who have a property right or claim against the estate being administered. The procedure for contesting a will typically begins by filing a document, often called a "caveat," with the probate court. The caveat is a formal notice asking the court to halt the probate process due to the contest. The contesting party must then file a petition outlining their objections to the will and the reasons behind them. This petition generally includes details about the decedent, the date of the will, the grounds for contesting, and the relationship of the contestant to the decedent. It's vital to remember that contesting a will is essentially a lawsuit against the estate, necessitating legal assistance. Since contesting a will is a lawsuit, it entails court fees, attorney compensation, and expenses related to evidence gathering. Depending on the complexity of the case, total fees can escalate into thousands of dollars. A contestation can trigger deep-seated family conflict or exacerbate existing tensions, causing emotional distress. The disputing parties often have differing views on the will's validity and the equitable distribution of the decedent's assets. This conflict can lead to strained relationships or even permanent estrangement among family members. The legal process can take months or even years to resolve, depending on the complexity of the case and the court's schedule. This delay can be particularly burdensome for beneficiaries who may be relying on their inheritance for financial stability. Courts generally uphold the decedent's wishes as expressed in the will unless compelling evidence proves otherwise. If the contest fails, the provisions of the will stand, and the contestant might be left to bear their own legal costs. In some cases, the court might even order the contestant to pay the other party's legal fees if the contestation is deemed frivolous. In this process, a neutral third party, known as the mediator, facilitates communication between the contesting parties to help them reach a mutually agreeable resolution. The mediator doesn't impose a decision but rather helps guide the discussion, allowing parties to voice their concerns and understand the other's perspective. Mediation can be particularly beneficial in preserving relationships, given its emphasis on cooperative problem-solving and consensus-building. It's also confidential and can be more flexible and less formal than court proceedings. In an arbitration process, an arbitrator or a panel thereof listen to the arguments and evidence presented by each side and then make a decision. The decision can be binding or non-binding, depending on what the parties agreed upon before the process began. Arbitration can be advantageous due to its typically quicker resolution timeframe compared to a court trial. It also allows for more flexible procedures and scheduling, and it keeps the dispute and its outcome private. Negotiation is a direct, often informal process where the contesting parties communicate their issues and attempt to reach an agreement. A negotiated settlement can be achieved with or without the assistance of legal representatives. In the case of a complex dispute, negotiations can take place in a series of steps or "rounds," allowing each party to make proposals or concessions. The goal is to find a middle ground that all parties can agree upon. While a will is typically contested during or before probate, it can, in some cases, be challenged post-probate, depending on jurisdictional rules, legal grounds, and timing considerations. Several legal grounds, such as lack of testamentary capacity, undue influence, fraud, forgery, or violation of will formalities, can be the basis for such a contest. These grounds necessitate strong evidence and detailed legal examination, underscoring the importance of experienced legal counsel. Will contests can lead to serious outcomes, including high legal costs, family discord, delay in the distribution of the estate, and the risk of an unsuccessful challenge. Hence, parties may consider alternative dispute resolution methods like mediation, arbitration, and negotiation to avoid a full court trial. These methods offer control, confidentiality, and potentially preserve relationships among disputants. Contesting a will after probate is a significant decision that demands a thoughtful understanding of several factors, compliance with procedural rules, and expert legal advice. Wills and Probate: Overview

Definition of a Will

Explanation of Probate

General Rules Around Contesting a Will

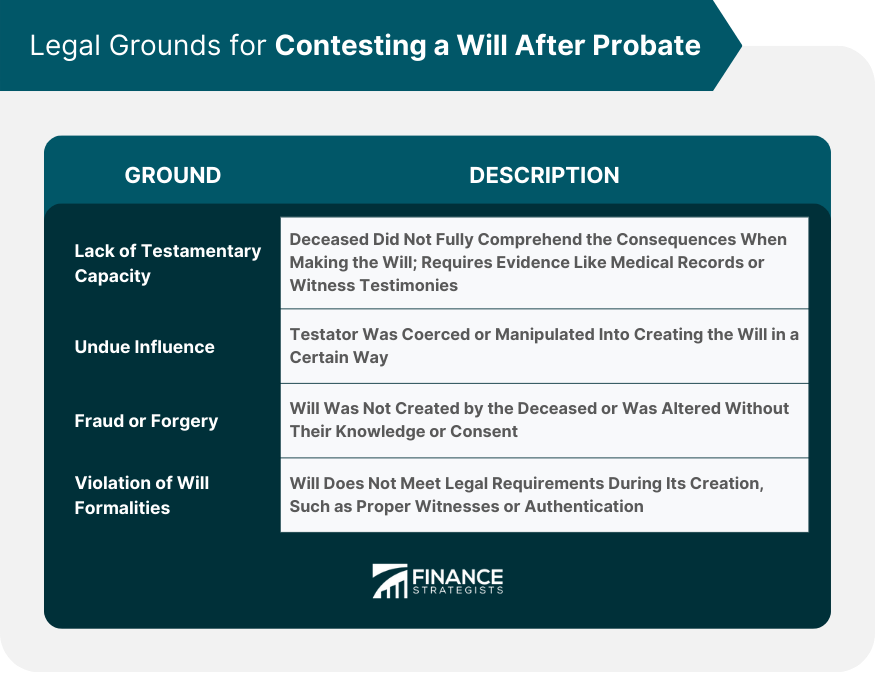

Legal Grounds for Contesting a Will After Probate

Lack of Testamentary Capacity

Undue Influence

Fraud or Forgery

Violation of Will Formalities

Process of Contesting a Will After Probate

Timing and Time Limits

Identifying Interested Parties

Filing a Contest

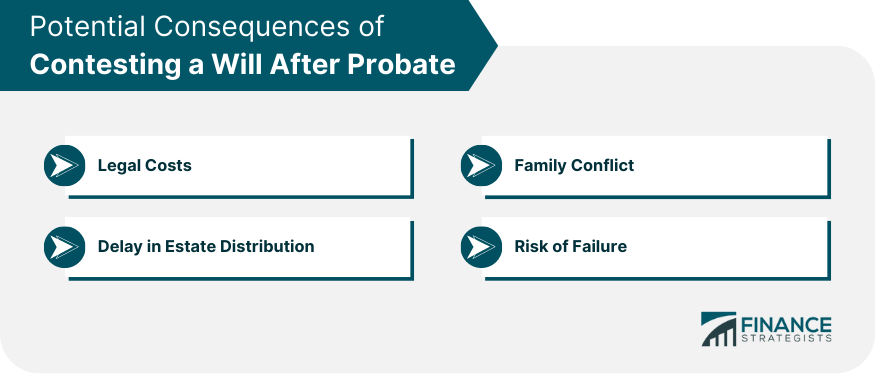

Potential Consequences of Contesting a Will After Probate

Legal Costs

Family Conflict

Delay in Estate Distribution

Risk of Failure

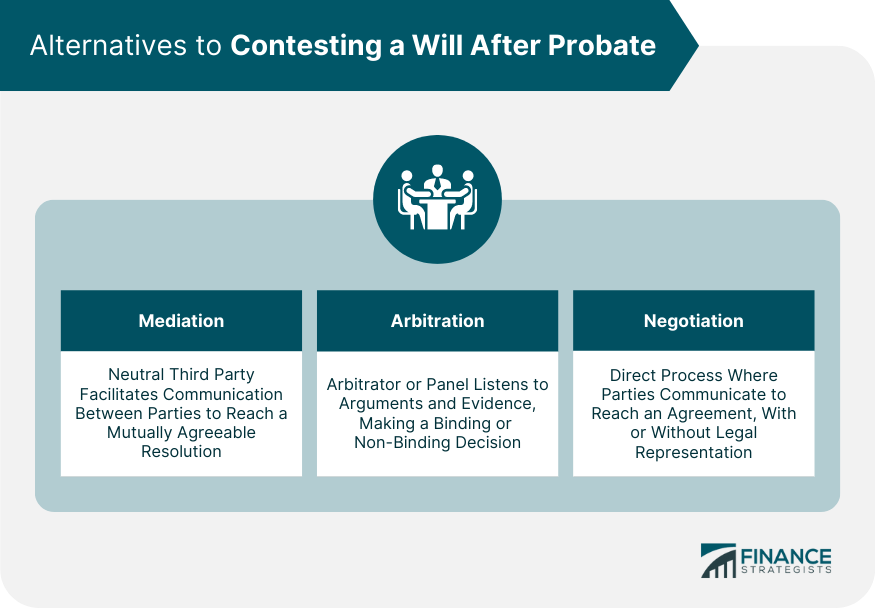

Alternatives to Contesting a Will After Probate

Mediation

Arbitration

Negotiation and Settlements

Final Thoughts

Can a Will Be Contested After Probate? FAQs

Yes, it is possible to contest a will even after probate has been granted. However, the process and grounds for contesting a will may vary depending on the jurisdiction.

Common reasons for contesting a will after probate include lack of testamentary capacity, undue influence, fraud, forgery, and the discovery of a more recent valid will.

The time limit for contesting a will after probate varies in different jurisdictions. It is advisable to consult with a local attorney to understand the specific timeframe applicable in your area.

Generally, anyone with standing or a legitimate interest in the estate can contest a will after probate. This typically includes beneficiaries named in a previous will, intestate heirs, or individuals who believe they were wrongly excluded from the will.

To contest a will after probate, you generally need to provide substantial evidence supporting your claim. This may include medical records, witness testimonies, expert opinions, or any other relevant documentation that challenges the validity of the will.

True Tamplin is a published author, public speaker, CEO of UpDigital, and founder of Finance Strategists.

True is a Certified Educator in Personal Finance (CEPF®), author of The Handy Financial Ratios Guide, a member of the Society for Advancing Business Editing and Writing, contributes to his financial education site, Finance Strategists, and has spoken to various financial communities such as the CFA Institute, as well as university students like his Alma mater, Biola University, where he received a bachelor of science in business and data analytics.

To learn more about True, visit his personal website or view his author profiles on Amazon, Nasdaq and Forbes.