Grantor retained annuity trusts (GRAT) are short-term irrevocable trusts which provide grantors with an annuity and pass on asset income to beneficiaries in a tax-free manner.

GRATs generally have a duration of between two to three years and their annuity payments are calculated based on the IRS hurdle rate or the 7520 rate – the market yield on government-issued debt.

The advantages of GRATs are its tax benefits and flexibility. It enables swapping of assets, if they underperform expectations.

The disadvantages of GRATs are an absence of tax benefits to the beneficiary, if the grantor passes away during the trust’s term. The grantor’s GRAT income is also taxed at regular income tax rates during its lifetime.

Have questions about Grantor Retained Annuity Trusts? Click here.

How Do GRATs Work?

Grantor retained annuity trusts are so-called because they allow grantors to retain annuity payments from the trust through a term period.

The amount of these annuity payments is calculated using the 7520 rate, a monthly interest rate set by the IRS, during the month of the trust’s creation.

After the term period for annuity payments is complete, the trust passes on income generated from the assets to a beneficiary without incurring an estate tax.

The generated income can also be rolled over to a new trust. Suppose Susan contributes $1 million worth of assets to a five-year trust that started on February 2015.

At that time, the 7520 rate was 2%. Susan will receive an annuity payment of approximately $212,156.57 in the first year.

At the end of the final year, Susan will receive an annuity payment of $213,392.51. Because Susan draws an annuity from the trust each year, the total value of gift to her beneficiaries decreases correspondingly.

At the end of the first year, the total value of her gift is calculated to be $8.59. By the end of the GRAT’s term, the total value of her gift is calculated to be -4.93.

Since both values are below the exemption limits, Susan is not required to pay a gift tax.

Susan’s trust also generates income at the rate of 5% per year. This is known as a remainder.

It does not belong to the trust and can be passed onto beneficiaries without corresponding estate taxes after the trust term expires.

At the end of the first year of Susan’s trust, it has a remainder of $103,982. In the final year of the trust’s term, in 2020, the trust has a remainder of $97, 153.22.

The sum of each year’s income is passed onto Susan’s beneficiary or rolled over to a new GRAT.

Types of GRATs

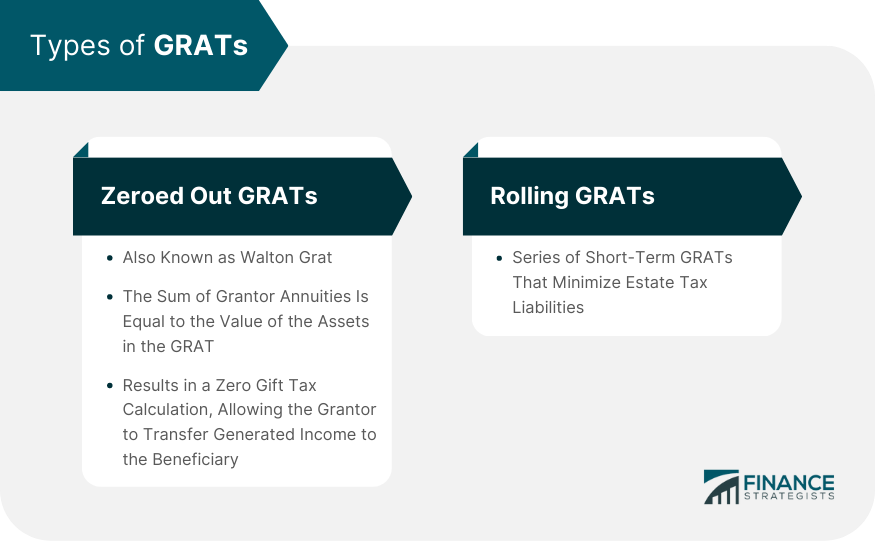

The two most common types of GRATs are as follows:

- Zeroed out GRATs: Also known as a Walton GRAT, a zeroed out GRAT is one in which the sum of grantor annuities is equal to the value of the assets contained in the GRAT.

This type of GRAT results in a gift tax calculation of zero and makes it possible for the grantor to transfer income generated from the assets to a beneficiary.

- Rolling GRATs: Rolling GRATs are a series of short-term GRATs that allow the grantor to minimize his or her estate tax liabilities.

If a grantor passes away before a GRAT term expires, then the remaining GRAT amount is added to his or her estate and may be liable for estate taxes.

A series of rolling short-term GRATs, generally lasting two years, ensures that only active GRATs are considered while the remaining estate amount is added to the beneficiary.

What Types of Assets Are Included in GRATs?

Assets that show potential for price increases should be included in GRATs.

For example, if you think that the price of a basket of stocks will go up in the next year or two, include them in a GRAT.

The price of the asset is discounted, meaning future cash flows are calculated at the time of its inclusion in the trust, and therefore it becomes easier for the GRAT to beat the IRS hurdle rate, even with minor price increases.

Why Are GRATs Useful?

GRATs are useful because they are relatively low-risk as compared to other trusts.

Even if a GRAT is unsuccessful, i.e., it doesn’t earn income from market returns, the grantor can still expect return of the principal amount invested in the trust.

In a worst-case scenario, where the principal is invaded to make annuity payments, the grantor can shut down the trust by withdrawing money contained in the trust.

GRATs are also useful in a low interest-rate environment. This is because the 7520 rate imposes a minimum rate of return for annuity payments made from the trust.

The lower this rate, the more of the trust’s earnings can be set aside for beneficiaries.

When rates are high, the annuity payments tend to be bigger, leaving lesser income for beneficiaries from the trust. GRATs are flexible.

You can swap assets from the GRAT using a “substitution transaction” during the annuity period without triggering tax.

Suppose market returns from stocks placed in a GRAT are not what you expected.

Then you can use a “substitution transaction” to swap the stocks with other instruments like, say, bonds. The swap will “freeze” the value of the shares to the time that they were withdrawn.

If you do not wish to freeze the value of shares, you can shut down the previous trust and roll over the assets into a new GRAT.

In this manner, GRAT grantors can cycle through multiple short-term GRATs to ensure that they are able to successfully negotiate gains on assets that are losing income.

The only cost associated with this strategy are the transaction expenses associated with a new GRAT.

Advantages and Disadvantages of GRATs

The advantages of GRATs are as follows:

- Depending on the gifted amount, GRATs can minimize or eliminate gift taxes completely.

- By inserting provisions during the time of trust creation, GRATs can be made flexible and allow for swapping of assets.

- GRATs can be rolled over several times to maximize asset income.

The disadvantages of GRATs are as follows:

- If the grantor dies before the GRAT’s term is complete, then the assets contained in it are passed onto his or her estate and may incur taxes, if they are above the federal exemption limit.

- GRATs can be unsuccessful during down markets, leading to their closure.

- Grantor income derived from a GRAT may be subject to regular taxes.

Grantor Retained Annuity Trusts FAQs

Grantor-retained annuity trusts (GRAT) are short-term irrevocable trusts which provide grantors with an annuity and pass on asset income to beneficiaries in a tax-free manner.

Also known as a Walton GRAT, a zeroed-out GRAT is one in which the sum of grantor annuities is equal to the value of the assets contained in the GRAT.

GRATs are most useful in a low interest rate environment because it minimizes annuity payments and increases asset income.

The disadvantages of GRATs are an absence of tax benefits to the beneficiary, if the grantor passes away during the trust’s term. The grantor’s GRAT income is also taxed at regular income tax rates during its lifetime.

Rolling GRATs are a series of short-term GRATs that allow the grantor to minimize his or her estate tax liabilities.

True Tamplin is a published author, public speaker, CEO of UpDigital, and founder of Finance Strategists.

True is a Certified Educator in Personal Finance (CEPF®), author of The Handy Financial Ratios Guide, a member of the Society for Advancing Business Editing and Writing, contributes to his financial education site, Finance Strategists, and has spoken to various financial communities such as the CFA Institute, as well as university students like his Alma mater, Biola University, where he received a bachelor of science in business and data analytics.

To learn more about True, visit his personal website or view his author profiles on Amazon, Nasdaq and Forbes.