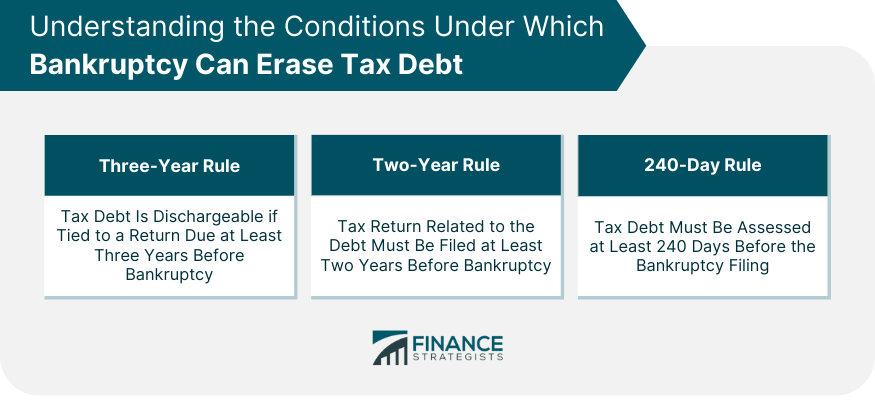

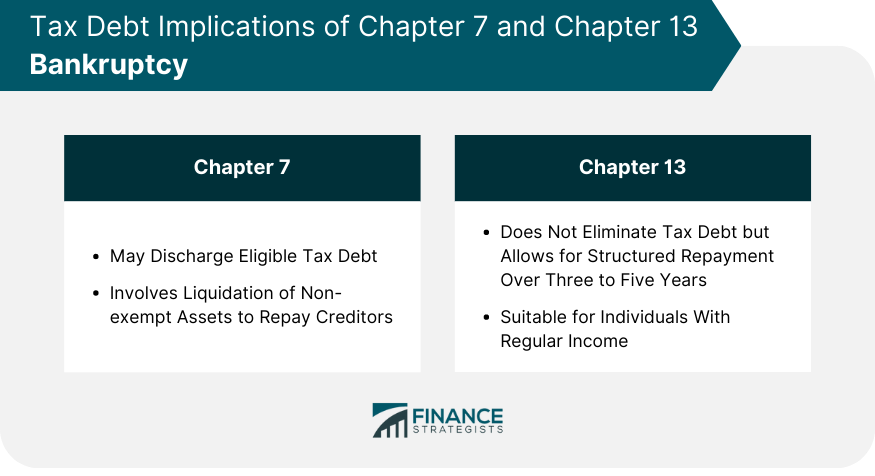

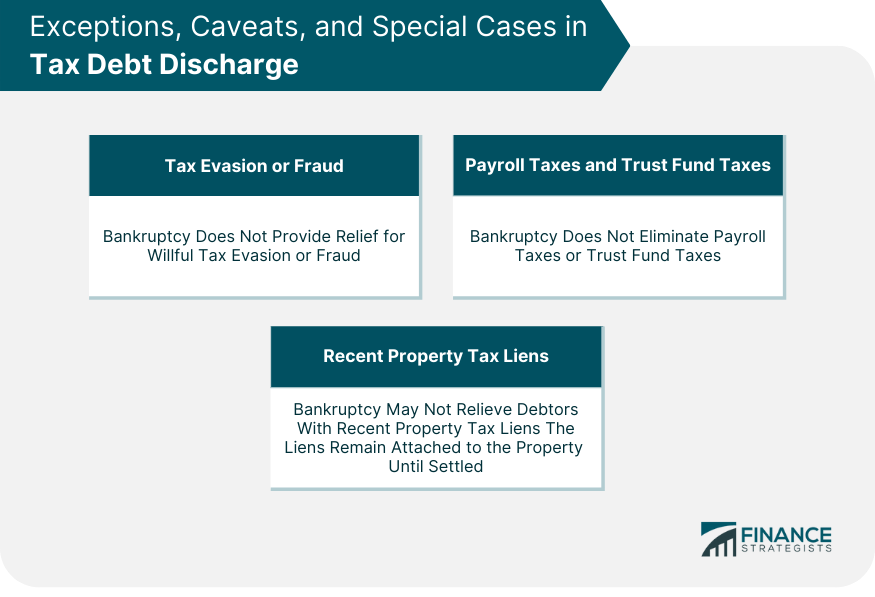

When financial hardships strike with increasing intensity, the thought of declaring bankruptcy can emerge as a beacon of hope for individuals and businesses alike. In its essence, bankruptcy is a legal process designed to provide a financial reboot for those beleaguered by insurmountable debt. One particular type of obligation that often poses significant burdens is tax debt—unpaid dues owed to governmental bodies. While these two concepts—bankruptcy and tax debt—may seem straightforward, their intersection can be a complex landscape to navigate. This is due to the fact that bankruptcy does not always lead to the discharge of tax debt, as it largely depends on the type of tax debt, its age, and specific rules associated with the bankruptcy chapter filed. Despite prevalent misconceptions, bankruptcy can indeed pave the way to eliminating tax debt, albeit under stringent conditions. Three pivotal rules delineate these conditions, creating the framework that determines if and when tax debt can be discharged through bankruptcy. Originating from U.S. bankruptcy law, the Three-Year Rule stipulates that tax debt is dischargeable if it is associated with a tax return due at least three years before filing for bankruptcy. This timeframe is inclusive of any extensions, allowing for the potential discharge of tax debt that dates back to a return due more than three years prior, given that other stipulations are met. The Two-Year Rule furthers the time-sensitive criteria for dischargeable tax debt, mandating that the tax return associated with the debt in question must have been filed a minimum of two years before the bankruptcy filing. The intention here is to prevent the instantaneous discharge of tax debt accumulated from a backlog of overdue returns filed just before bankruptcy. Lastly, the 240-Day Rule sets forth that the tax debt should have been assessed at least 240 days before the bankruptcy filing—or not assessed at all—for it to be dischargeable. This rule ensures that sufficient time has elapsed since the tax assessment before a bankruptcy petition is filed. Bankruptcy proceedings can take various forms, with Chapter 7 and Chapter 13 being the most common for individuals. These chapters represent different routes to addressing financial insolvency and have distinctive implications for tax debt. Often referred to as "liquidation bankruptcy," Chapter 7 bankruptcy involves the sale—or liquidation—of a debtor's non-exempt assets conducted by a bankruptcy trustee. Proceeds from this sale are used to repay creditors. In terms of tax debt, Chapter 7 bankruptcy might present a light at the end of the tunnel for individuals burdened by older, lingering tax debt, provided it meets the conditions of the three previously discussed rules. Chapter 13 bankruptcy, sometimes known as a "wage earner's plan," enables individuals with regular income to devise a plan to repay their debts. This plan often stretches over three to five years, providing a structured, systematic method for debt repayment. While Chapter 13 bankruptcy does not eliminate tax debt, it can offer a more manageable, long-term solution for repayment. While bankruptcy can offer a pathway to relief from some types of tax debt, it is vital to recognize the exceptions and special circumstances where tax debt cannot be eliminated. Bankruptcy provides no shelter for tax debt arising from willful tax evasion or fraud. This extends to scenarios where a fraudulent tax return was filed, or a deliberate attempt was made to dodge paying taxes. Bankruptcy does not wash away certain types of tax debts, such as payroll taxes or trust fund taxes. Trust fund taxes refer to taxes that an employer withholds from an employee's wages. Tax debts tied to unfiled returns or certain penalties related to tax fraud also stand resistant to bankruptcy discharges. For debtors with recent property tax liens, bankruptcy might not offer the relief they seek. If a tax lien has been recorded against a property before a bankruptcy filing, that lien will continue to bind the property, necessitating its settlement before the property's sale. Declaring bankruptcy is a weighty decision, one that can entail a host of ramifications. One of the most tangible impacts of filing for bankruptcy is the blow dealt to your credit score, which can make obtaining future credit or loans a Herculean task. The fact of your bankruptcy filing, as well as the discharge date, can linger on your credit report for a decade. Beyond the financial consequences, bankruptcy can exact a severe psychological toll. Feelings of failure, embarrassment, or loss can haunt those who have declared bankruptcy. The public nature of the process can intensify these feelings, contributing to a sense of personal exposure and stigma. Bankruptcy is not a "get out of jail free" card that can be used repeatedly. Stringent restrictions are placed on the frequency of bankruptcy filings, which can range from two to eight years, depending on the type of bankruptcy initially filed. Given the weighty consequences and limitations of bankruptcy, it's vital to consider alternative avenues for tackling tax debt. An installment agreement with the IRS allows for the repayment of tax debt in monthly installments. If you owe $50,000 or less, you may qualify to apply for such an agreement online. An offer in compromise is an agreement wherein the IRS agrees to settle a taxpayer's liabilities for less than the full amount owed. The IRS will only entertain an offer in compromise when they believe the offered amount represents the maximum they could expect to collect within a reasonable period. When paying any portion of your tax debt is beyond your means, the IRS may declare you "currently not collectible," which effectively halts collection activities until your financial situation improves. However, it is crucial to note that your debt doesn't vanish—penalties and interest will continue to accrue. Bankruptcy can, under certain circumstances, be a potential pathway to eliminating tax debt. However, navigating these conditions requires understanding various rules and exceptions, such as the Three-Year, Two-Year, and 240-Day rules, as well as the type of bankruptcy filed (Chapter 7 or Chapter 13). It's also vital to remember that bankruptcy does not offer respite for all tax debts, particularly in cases of tax evasion, fraud, payroll taxes, or trust fund taxes. The decision to declare bankruptcy should be made carefully, considering the long-term implications on credit score, psychological impact, and restrictions on future filings. Various alternatives to bankruptcy, like installment agreements or offers in compromise, can provide alternate routes to resolving tax debt. Professional guidance from bankruptcy attorneys and tax experts is strongly advised to ensure the most effective and well-informed approach to tackling such complex financial challenges.Understanding Bankruptcy and Tax Debt

Can Bankruptcy Clear Tax Debt?

Three-Year Rule: A Test of Time

Two-Year Rule: A Timely Filing

240-Day Rule: An Assessment Period

Tax Debt Implications of Chapter 7 and Chapter 13 Bankruptcy

Chapter 7 Bankruptcy: Liquidation and Potential Relief

Chapter 13 Bankruptcy: Structured Repayment

Exceptions, Caveats, and Special Cases in Tax Debt Discharge

Tax Evasion or Fraud: No Relief

Payroll Taxes and Trust Fund Taxes: Standing Firm

Recent Property Tax Liens: Bound to the Property

Consequences of Declaring Bankruptcy

Credit Score Impact

Stigma and Psychological Impact

Restrictions on Future Bankruptcy Filings

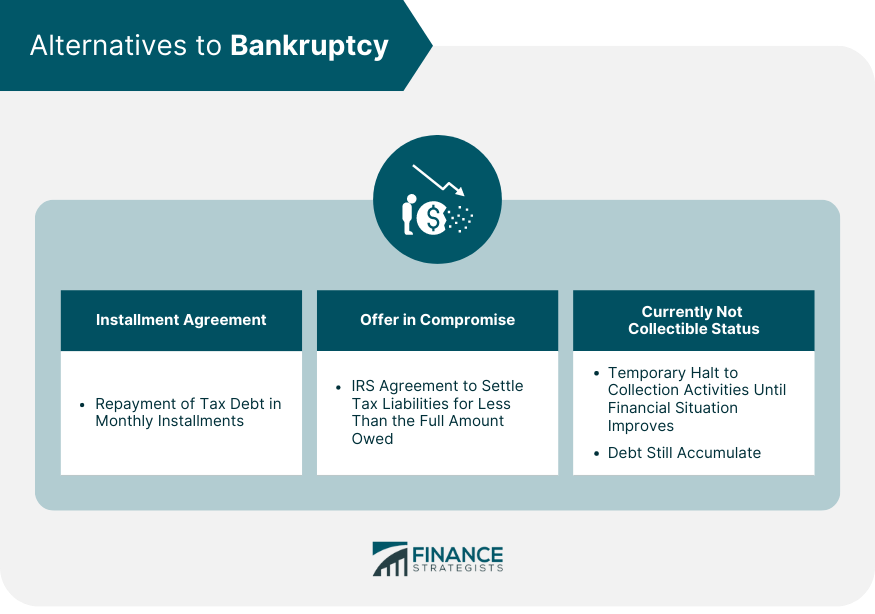

Alternatives to Bankruptcy: Other Routes to Tax Debt Resolution

Installment Agreement

Offer in Compromise

Currently Not Collectible Status

Bottom Line

Does Bankruptcy Clear Tax Debt? FAQs

Yes, bankruptcy can clear specific tax debts if they adhere to the Three-Year, Two-Year, and 240-Day rules established in U.S. bankruptcy law.

Yes, Chapter 7 bankruptcy may clear eligible tax debts, while Chapter 13 allows for the structured repayment of all debts, including tax debts.

Bankruptcy cannot clear tax debts arising from tax evasion, fraud, payroll taxes, trust fund taxes, or recent property tax liens.

Consequences include a significant impact on your credit score, possible psychological distress, and restrictions on future bankruptcy filings.

Alternatives include an installment agreement with the IRS, an offer in compromise, or obtaining a "currently not collectible" status.

True Tamplin is a published author, public speaker, CEO of UpDigital, and founder of Finance Strategists.

True is a Certified Educator in Personal Finance (CEPF®), author of The Handy Financial Ratios Guide, a member of the Society for Advancing Business Editing and Writing, contributes to his financial education site, Finance Strategists, and has spoken to various financial communities such as the CFA Institute, as well as university students like his Alma mater, Biola University, where he received a bachelor of science in business and data analytics.

To learn more about True, visit his personal website or view his author profiles on Amazon, Nasdaq and Forbes.