An example of a financial product that may be divided into tranches is a mortgage back security, or MBS. An MBS is made up of several mortgage pools with varying degrees of risk and times to maturity. Therefore, the MBS may be divided into tranches in order to offer slices of the portfolio to different investors. For example, the portfolio may have tranches with one year, two year, five year, and twenty year maturities, all with varying yields. A tranche is a segment of a pooled collection of securities, typically debt vehicles, that are split up by risk, time to maturity, or other characteristics to be appealing to different investors. The tranches of a larger asset pool are defined in transaction documentation and are assigned a different class of notes and different credit ratings. Tranches often constitute different portions of a debt or security offering that is partitioned into varying degrees of risk, maturity, or other classifying features. This division allows investors to choose the piece or tranche that best aligns with their investment objectives, risk tolerance, and time horizon. Senior tranches, often called the 'A-Tranche,' represent the most secure portions of a debt security. These tranches have the highest claim on the underlying assets' cash flows and are first to receive payments. Due to their superior position in the payment hierarchy, senior tranches usually have lower yields compared to other tranches, reflecting their reduced risk. Mezzanine tranches hold an intermediate position in the hierarchy of a structured finance transaction. Positioned between the senior and junior tranches, mezzanine tranches entail more risk than senior tranches but less than junior tranches. Consequently, their yield is also intermediate, offering investors a balance between risk and return. Junior tranches, also known as equity or 'C-Tranche,' sit at the bottom of the payment hierarchy. They are the last to receive any payments and bear the most significant risk. As a result, junior tranches often provide higher potential yields to compensate investors for their higher risk exposure. Tranches are defined by their risk profile, which is determined by their position in the payment hierarchy. Senior tranches carry the least risk, followed by mezzanine and junior tranches, respectively. The risk level of a tranche directly impacts its yield and return. The yield and return on tranches also vary according to their risk. Higher risk tranches offer greater potential returns to attract investors, while lower risk tranches offer lower yields but provide more stability and security. Credit ratings agencies assign ratings to tranches based on their perceived risk. These ratings can significantly influence a tranche's marketability and pricing. Typically, senior tranches receive the highest ratings, while junior tranches receive the lowest. Tranche slicing refers to the division of a securities offering into different segments or tranches. This process allows for differentiation in risk, return, and maturity, catering to the diverse needs of investors. The cash flow waterfall refers to the order in which cash flows from the underlying assets are distributed to the tranches. The senior tranche is paid first, followed by mezzanine, and finally, the junior tranche. This sequential payment structure ensures that the riskier tranches only receive payments after the less risky tranches have been fully paid. Subordination levels determine the order in which losses are absorbed. In the case of default or loss in the underlying assets, the junior tranches absorb the loss first, followed by the mezzanine, and finally, the senior tranche. This structure provides additional protection to the senior tranche, enhancing its credit quality. Tranching allows for the efficient allocation of risk among different investor groups. By splitting the security into different risk levels, investors can choose the tranche that best suits their risk appetite. Tranches provide customization options to investors. Depending on their risk tolerance, return expectations, and investment horizon, investors can select the tranche that best meets their needs. Tranching enhances the liquidity of securities by attracting a wider range of investors. With varied risk-return profiles, more investors can participate, improving the liquidity and marketability of the security. Credit risk, the risk of default on the underlying assets, is a major concern for tranche investors. While senior tranche investors are somewhat insulated, mezzanine and junior tranche investors face higher credit risk. Market risk is another significant risk for tranche investors. Changes in interest rates, economic conditions, or the financial market can affect the value of the tranches and the underlying assets. While tranching generally enhances liquidity, there can still be liquidity risk, particularly for lower-rated tranches. In a downturn, these tranches may be difficult to sell at a favorable price. Tranches are commonly used in asset-backed securities (ABS). These are financial securities backed by a pool of assets, such as loans, leases, credit card debt, or receivables. ABS transactions are typically structured into tranches to cater to different investor needs. Collateralized debt obligations (CDOs) also utilize tranches. CDOs pool various fixed-income assets, such as bonds and loans, and issue new securities backed by these assets. The securities are then split into tranches with differing risk and return profiles. Mortgage-backed securities (MBS) represent another key use of tranches. MBS pool residential or commercial mortgages and issue securities backed by these mortgages. These securities are then divided into tranches, allowing investors to choose based on their risk tolerance and return expectations. Examples of other securities that may be split up into tranches are bonds, mortgages, loans, and insurance policies. Bonds, which are debt instruments issued by governments, municipalities, or corporations, can be partitioned into tranches to cater to different investor preferences. Similarly, mortgages and loans can be securitized and divided into tranches. For example, a pool of residential mortgages can be bundled together and transformed into mortgage-backed securities (MBS). In addition, certain insurance policies, such as catastrophe bonds or insurance-linked securities (ILS), can be structured as tranches. These tranches represent different levels of risk exposure to specific events, such as natural disasters. Tranches play a crucial role in finance, offering investors a flexible and customizable approach to investing. By dividing financial products into segments based on risk, maturity, and other characteristics, tranches cater to investors' diverse preferences and objectives. The benefits of tranches include efficient risk allocation, customization options, and enhanced liquidity. Tranches allow investors to select the segment that aligns with their risk appetite, return expectations, and investment horizon. However, tranches also carry risks, such as credit risk, market risk, and liquidity risk. Default on underlying assets, market fluctuations, and potential difficulties in selling lower-rated tranches can pose challenges. Tranches are commonly used in asset-backed securities, collateralized debt obligations, and mortgage-backed securities, offering investors the opportunity to participate in different segments of these instruments. What Are Tranches in Finance?

Define Tranches In Simple Terms

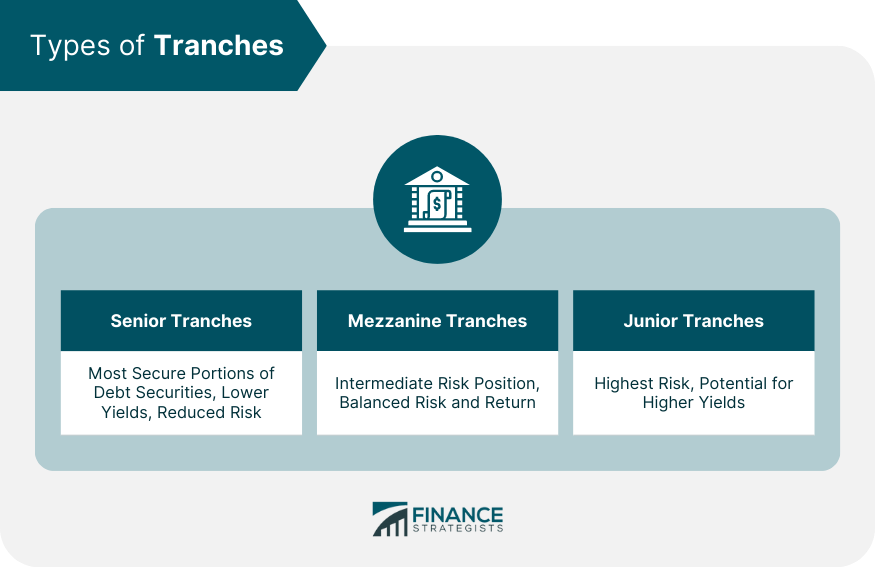

Types of Tranches

Senior Tranches

Mezzanine Tranches

Junior Tranches

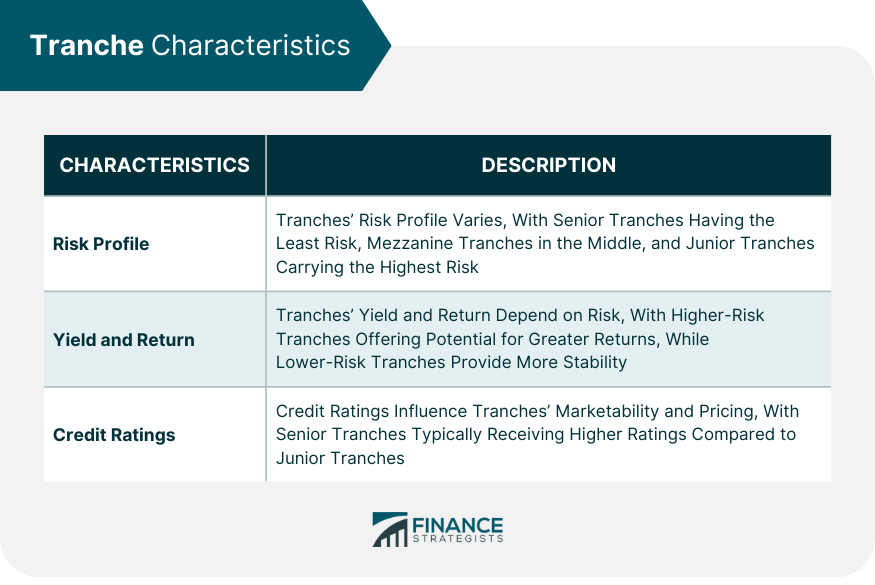

Characteristics of Tranches

Risk Profile

Yhield and Return

Credit Ratings

Structuring Tranches

Tranche Slicing

Cash Flow Waterfall

Subordination Levels

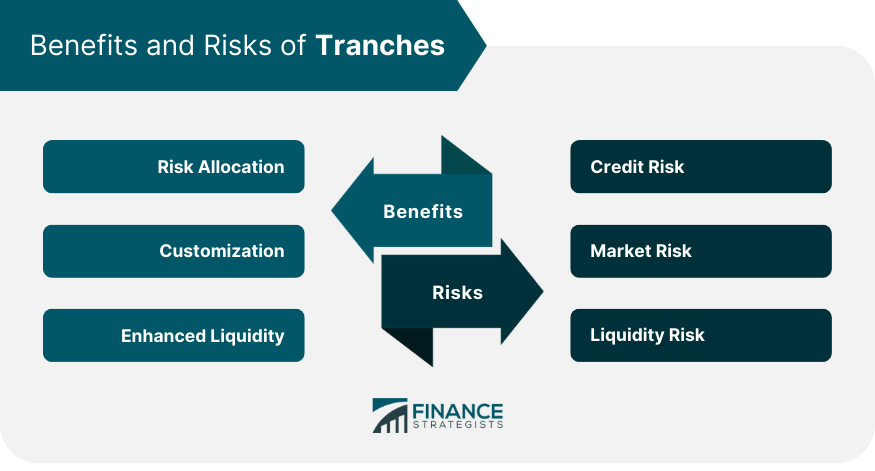

Benefits of Tranches

Risk Allocation

Customization

Enhanced Liquidity

Risks of Tranches

Credit Risk

Market Risk

Liquidity Risk

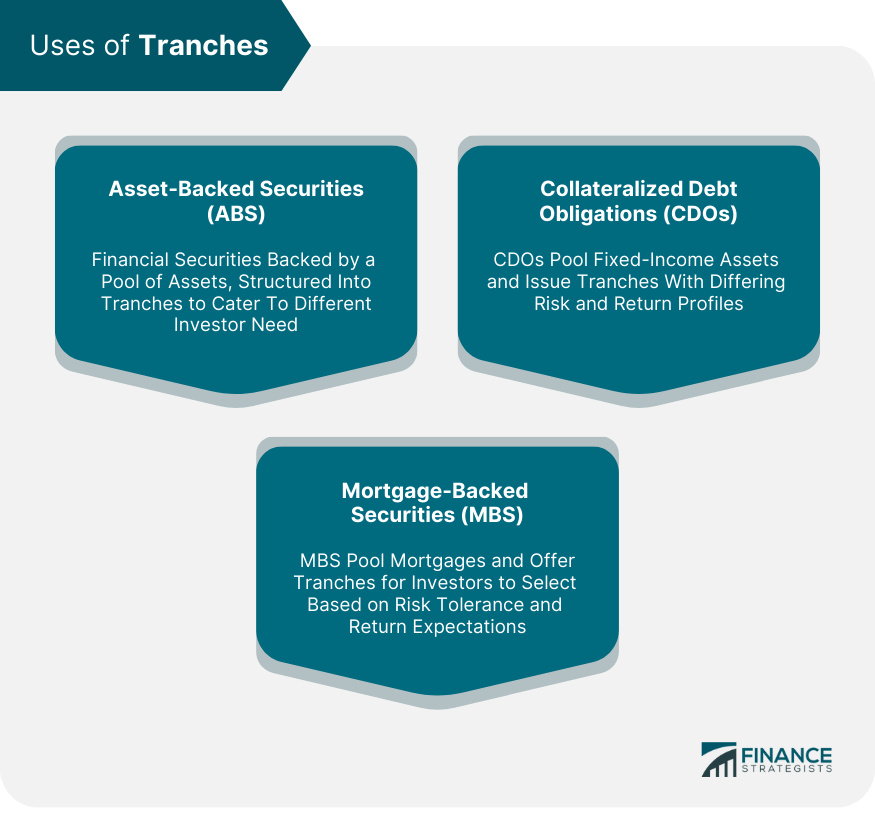

Uses of Tranches

Asset-Backed Securities (ABS)

Collateralized Debt Obligations (CDOs)

Mortgage-Backed Securities (MBS)

Example of Other Securities

Conclusion

Tranches FAQs

A Tranche is a segment of a pooled collection of securities, typically debt vehicles, that are split up by risk, time to maturity, or other characteristics to be appealing to different investors.

An example of a financial product that may be divided into tranches is a mortgage-backed security or MBS.

The tranches of a larger asset pool are defined in transaction documentation and are assigned a different class of notes and different credit ratings.

For example, different portfolios may have tranches with one-year, two-year, five-year, and twenty-year maturities, all with varying yields.

Examples of other securities that may be split up into tranches are bonds, mortgages, loans, and insurance policies.

True Tamplin is a published author, public speaker, CEO of UpDigital, and founder of Finance Strategists.

True is a Certified Educator in Personal Finance (CEPF®), author of The Handy Financial Ratios Guide, a member of the Society for Advancing Business Editing and Writing, contributes to his financial education site, Finance Strategists, and has spoken to various financial communities such as the CFA Institute, as well as university students like his Alma mater, Biola University, where he received a bachelor of science in business and data analytics.

To learn more about True, visit his personal website or view his author profiles on Amazon, Nasdaq and Forbes.