Nonprofit organizations are entities that operate primarily to serve a public or communal interest rather than to generate profit for owners or shareholders. While they can, and often do, earn revenues, the key distinction is how these revenues are used. Instead of distributing profits to shareholders or owners, nonprofits reinvest these revenues back into their mission and organizational objectives. Being "tax-exempt" means that the organization is not required to pay certain taxes, especially federal income taxes. To obtain this status, nonprofits typically apply with the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) and must demonstrate that they operate exclusively for exempt purposes as outlined in Section 501(c) of the Internal Revenue Code. It's important to note, however, that not all nonprofits automatically receive tax-exempt status. The designation is reserved for those that meet specific criteria and undergo a rigorous application process. The process of filing taxes for nonprofits varies somewhat from that of for-profit entities. Many nonprofits seek tax-exempt status under Section 501(c) of the Internal Revenue Code. However, obtaining this status requires a separate application process involving forms like IRS Form 1023 or Form 1023-EZ. Depending on the size and nature of the nonprofit, different forms may be required: Form 990 (Return of Organization Exempt from Income Tax): This is the standard form for larger tax-exempt organizations to report their financial activities to the IRS. Form 990-EZ: A shorter version of Form 990, this is suitable for organizations with gross receipts less than $200,000 and total assets less than $500,000. Form 990-N (e-Postcard): Designed for organizations with gross receipts of $50,000 or less. Form 990-PF: Specifically for private foundations, regardless of income size. Form 990-T: If a nonprofit earns income that's unrelated to its exempt purpose, it may be subject to Unrelated Business Income Tax (UBIT) and must file this form. While tax-exempt nonprofits may not owe federal income taxes, they still have reporting obligations. These forms typically require details on: Information about board members, officers, and employees Compensation data Details about program services Information about donors (without revealing names) Besides federal taxes, nonprofits may have state-level tax obligations, which might include income, sales, employment, or property taxes. The specifics vary by state, so organizations should be familiar with local regulations. Tax-exempt status doesn't protect nonprofits from all taxes. For instance: Revenue earned from activities unrelated to the nonprofit's main purpose (e.g., advertising income) might be taxable. Nonprofits must still withhold employee taxes and pay employment-related taxes. Like any other entity, nonprofits should maintain regular and accurate financial records. This not only simplifies the tax-filing process but also ensures transparency and trustworthiness in the eyes of donors, members, and the public. Tax-exempt organizations must file their respective forms every year, typically by the 15th day of the 5th month after their accounting period ends (May 15th for calendar-year organizations). Failing to file for three consecutive years can result in the automatic revocation of tax-exempt status. Here's a comprehensive guide to the key dates and deadlines nonprofits should mark on their calendars. For most tax-exempt organizations, the typical deadline to file is the 15th day of the 5th month following the end of their taxable year. In practical terms: For organizations operating on a calendar year (ending December 31), the deadline is May 15th. For those operating in a fiscal year, the deadline varies. For instance, if the fiscal year ends on June 30, the filing deadline would be November 15th. If an organization needs additional time, it can request an extension: Form 8868: Application for Automatic Extension of Time To File an Exempt Organization Return. This grants an automatic 6-month extension, pushing the deadline to the 15th day of the 11th month after the close of the taxable year. If a nonprofit earns income from activities unrelated to its primary purpose, it might need to pay UBIT. The deadline for Form 990-T (Exempt Organization Business Income Tax Return) usually matches the standard annual filing deadline. Employment tax obligations aren't annual but quarterly. Form 941 (Employer's Quarterly Federal Tax Return) is due on the last day of the month following the end of the quarter (e.g., April 30th, July 31st, October 31st, and January 31st). Varies by state, so nonprofits should consult local regulations. Typically, states may have separate deadlines for sales taxes, employment taxes, and other state-specific obligations. Some states require nonprofits to renew their tax-exempt status periodically. The frequency and specific deadlines vary by state. Organizations should keep a keen eye on state tax agency notifications. Here are the potential ramifications that nonprofits might encounter when they fail to meet specific deadlines. For nonprofits that miss the mark, escalating late filing fees are imposed, accumulating for each month the form remains overdue. If taxes are owed, they will not only accumulate but will also accrue interest until they're settled. This added financial burden could strain an already limited nonprofit budget, diverting funds from core programs and initiatives. When a nonprofit neglects to file the appropriate version of Form 990 for three consecutive years, the IRS doesn't hesitate—it automatically revokes tax-exempt status. Regaining this crucial status isn't straightforward. It often involves navigating a complex reapplication process and settling any outstanding back taxes. Transparent and timely filings are pivotal in maintaining this trust. Delays or omissions in reporting can raise doubts about an organization's financial integrity and management. Such suspicions, once aroused, can deter potential donors, undermining an essential source of funding and support for the nonprofit's mission. Individual states have their own sets of rules and deadlines, and missing these can result in state-imposed fines. Beyond monetary penalties, non-compliance at the state level might lead to the loss of valuable state-specific exemptions, like those for sales or property taxes, adding another layer of financial strain to the organization. Beyond immediate penalties, late filings often come with hidden administrative costs. There might be a need for extra documentation, in-depth explanations, or even supplementary forms—all of which increase the workload for nonprofit administrators. Plus, once an organization is flagged for late or inconsistent filings, it can find itself under increased scrutiny in subsequent years, leading to additional reporting pressures. Legal repercussions are a looming threat for nonprofits that miss their filing deadlines, especially if these oversights result in financial discrepancies or any form of misrepresentation. Stakeholders, including donors or beneficiaries, might take legal action, leading to potential lawsuits. Addressing such legal challenges not only tarnishes the organization's reputation but also incurs significant legal costs. Many grant-making bodies meticulously vet applicant organizations, requiring evidence of consistent regulatory compliance. A history marred by missed deadlines can render a nonprofit ineligible for these grants. Additionally, financial inconsistencies or reporting issues can trigger mandatory financial audits, introducing another set of expenses and administrative challenges. Understanding nonprofit taxes is crucial for organizations working to benefit the public. Nonprofits differ from businesses as they reinvest their earnings into their mission instead of making profits for owners. Gaining tax-exempt status means not paying certain taxes, but it involves navigating IRS rules and applying through specific forms. While nonprofits are spared federal income taxes, they still need to report financial details. The timing of these reports is important, and missing deadlines can lead to penalties, loss of tax-exempt status, decreased trust, state-level issues, extra administrative work, legal problems, and trouble securing future funds. Nonprofits must be vigilant about these responsibilities to keep their reputation intact, maintain trust, and secure their mission's success. By meeting these obligations, nonprofits can uphold their credibility, ensure financial stability, and keep positively impacting society.Nonprofit Taxation

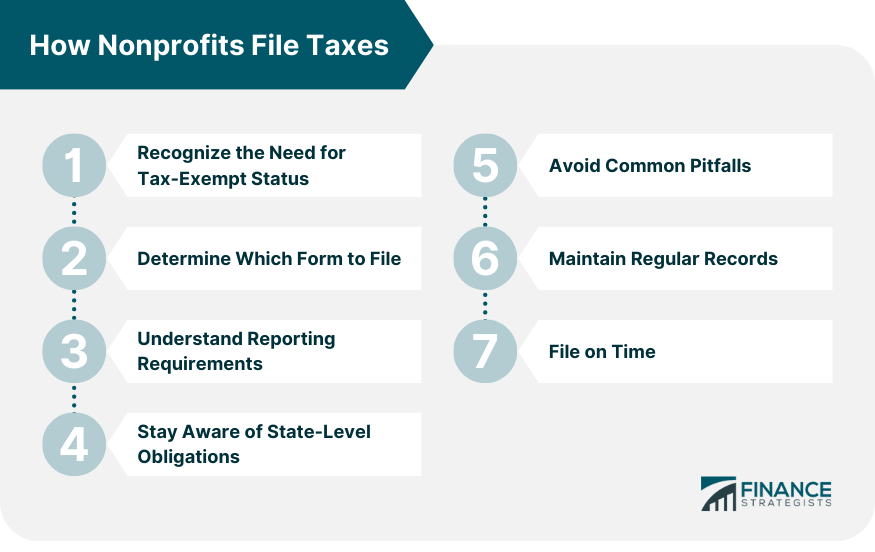

How Nonprofits File Taxes

Recognize the Need for Tax-Exempt Status

Determine Which Form to File

Understand Reporting Requirements

Stay Aware of State-Level Obligations

Avoid Common Pitfalls

Maintain Regular Records

File on Time

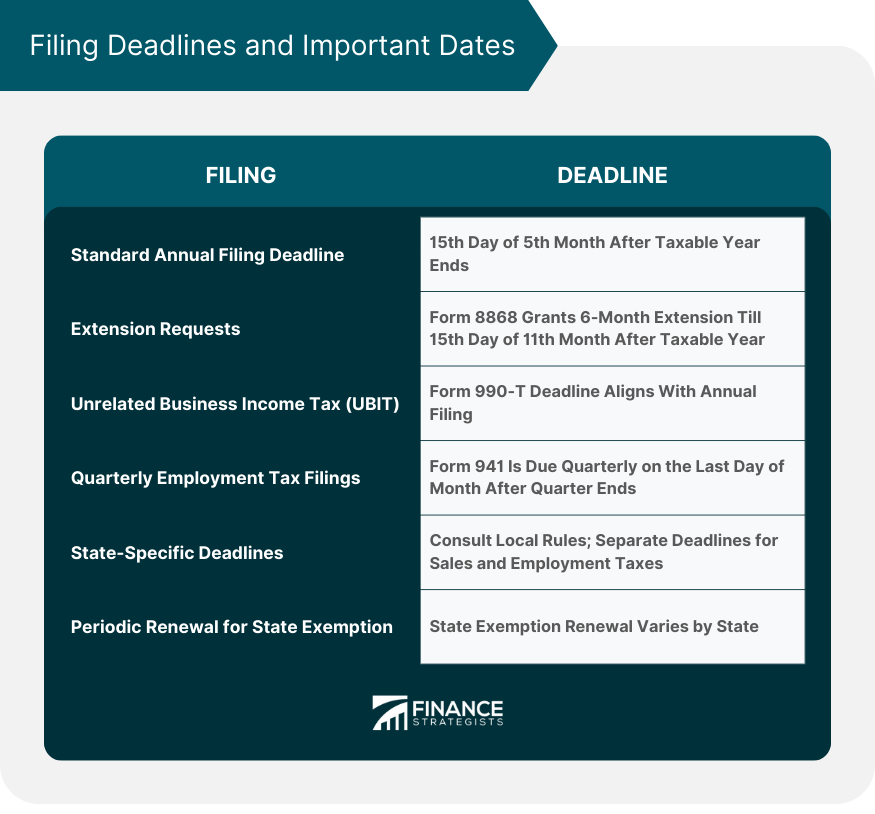

Filing Deadlines and Important Dates

Standard Annual Filing Deadline

Extension Requests

Unrelated Business Income Tax (UBIT)

Quarterly Employment Tax Filings

State-Specific Deadlines

Periodic Renewal for State Exemption

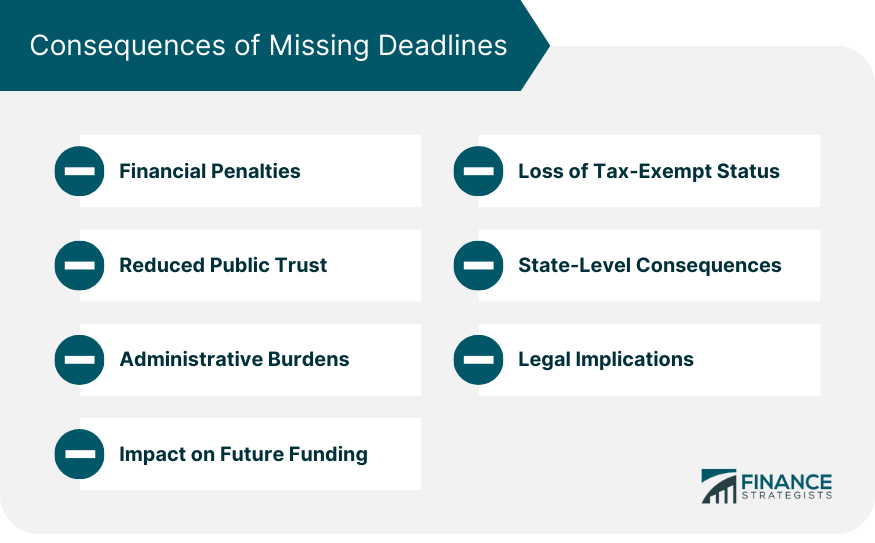

Consequences of Missing Deadlines

Financial Penalties

Loss of Tax-Exempt Status

Reduced Public Trust

State-Level Consequences

Administrative Burdens

Legal Implications

Impact on Future Funding

Conclusion

How Do Nonprofits File Taxes? FAQs

Nonprofit organizations are entities established to serve the public interest. They focus on missions such as charity, education, religion, or social services, rather than making profits for owners.

Nonprofits file taxes by submitting forms specific to their size and activities, such as Form 990, 990-EZ, or 990-N. These forms provide financial information to the IRS while showcasing their mission-driven work.

Not all nonprofits are automatically exempt from taxes. They need to apply for tax-exempt status by demonstrating their alignment with IRS rules, usually under Section 501(c) of the Internal Revenue Code.

Missing tax filing deadlines can lead to penalties, loss of tax-exempt status, decreased public trust, and potential legal issues. Timely filing is essential to maintain financial integrity and credibility.

Yes, in addition to federal taxes, nonprofits may have state-level tax obligations. These can include income, sales, employment, or property taxes. State regulations vary, so nonprofits should be aware of local requirements.

True Tamplin is a published author, public speaker, CEO of UpDigital, and founder of Finance Strategists.

True is a Certified Educator in Personal Finance (CEPF®), author of The Handy Financial Ratios Guide, a member of the Society for Advancing Business Editing and Writing, contributes to his financial education site, Finance Strategists, and has spoken to various financial communities such as the CFA Institute, as well as university students like his Alma mater, Biola University, where he received a bachelor of science in business and data analytics.

To learn more about True, visit his personal website or view his author profiles on Amazon, Nasdaq and Forbes.