The 183-Day Rule is a general principle used by tax authorities worldwide to determine an individual's tax residency status. It states that an individual who spends more than 183 days in a tax jurisdiction during a given tax year or a 12-month period is considered a tax resident of that jurisdiction. This rule is essential in determining an individual's tax obligations, as tax residents are typically subject to taxation on their worldwide income. In contrast, non-residents are only taxed on income sourced from that jurisdiction. The primary purpose of the 183-Day Rule is to provide a clear and objective criterion for determining tax residency, ensuring that taxpayers and tax authorities can quickly establish an individual's tax obligations. This rule is essential in the context of increasing globalization and cross-border employment, as individuals frequently live and work in multiple jurisdictions throughout their careers. By clarifying an individual's tax residency status, the 183-Day Rule helps prevent double taxation or tax evasion and promotes transparency and fairness in international taxation. The 183-Day Rule originates in the Model Tax Convention developed by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) in the 1960s. The Model Tax Convention is a template for bilateral tax treaties between countries, which aim to prevent double taxation and tax evasion in international transactions. Since its introduction, the 183-Day Rule has been adopted by numerous countries as a standard criterion for determining tax residency, either through domestic legislation or tax treaties. Determining tax residency using the 183-Day Rule requires understanding the physical presence and substantial presence tests. Additionally, taxpayers should be aware of the tax implications for residents and non-residents and the role of tax treaties in applying the rule. The physical presence test is a straightforward application of the 183-Day Rule. Under this test, an individual is considered a tax resident if they spend more than 183 days in a tax jurisdiction during a tax year or a 12-month period. This test is commonly used by countries like the United States, the United Kingdom, and Canada to determine tax residency. The substantial presence test is a more nuanced application of the 183-Day Rule and is often used by countries with more complex tax systems, like the United States. Under this test, an individual is considered a tax resident if they meet the following criteria: They are present in the tax jurisdiction for at least 31 days during the current tax year. They have a total of 183 days of presence in the tax jurisdiction during the current tax year and the two preceding tax years. Each day of presence in the current tax year is counted as one day, each day of presence in the first preceding tax year is counted as one-third of a day, and each day of presence in the second preceding tax year is counted as one-sixth of a day. The tax implications of the 183-Day Rule vary depending on an individual's tax residency status. Tax residents are typically subject to taxation on their worldwide income, including employment, business, investment, and other sources of income. Depending on the tax jurisdiction's regulations, they may also be eligible for various deductions, exemptions, and tax credits. Non-residents, on the other hand, are only taxed on income sourced from the tax jurisdiction where they are not residents. This can include employment income earned while working in the jurisdiction, rental income from properties located there, and income from businesses operating within the jurisdiction. Non-residents may also be subject to withholding taxes on certain types of income, such as dividends and interest. Tax treaties play a significant role in applying the 183-Day Rule, as they can modify or override the domestic tax laws of the countries involved. Tax treaties are agreements between two or more countries that aim to prevent double taxation and tax evasion, and they often contain provisions related to the 183-Day Rule. In some cases, tax treaties can provide a more favorable application of the 183-Day Rule by excluding certain types of income or days of presence from the calculation. For example, a tax treaty may stipulate that income from employment is only taxable in the country where the work is performed if the employee is present in the country for less than 183 days during the relevant period. In other cases, tax treaties can provide a tie-breaker rule to determine an individual's tax residency when they meet the 183-Day Rule criteria in multiple jurisdictions. Understanding the 183-Day Rule's impact on income sourcing is crucial, as it determines the tax treatment of various types of income for residents and non-residents. Employment income earned by non-residents while they are present in a tax jurisdiction for less than 183 days is generally sourced to the country where the work is performed. This income may be subject to withholding taxes and other tax obligations in the country, depending on the applicable tax laws and treaties. If a non-resident employee is present in a tax jurisdiction for more than 183 days during a tax year or a 12-month period, their employment income may be considered sourced in the jurisdiction and subject to taxation. In some cases, tax treaties can modify this rule, allowing the employee to avoid taxation in the country where they work, provided that certain conditions are met, such as working for a foreign employer or not having a permanent establishment in the country. Passive income, such as dividends, interest, and royalties, is typically sourced to the country where the payer is a resident. Non-residents may be subject to withholding taxes on passive income, depending on the tax jurisdiction's rules and any applicable tax treaties. On the other hand, residents are generally taxed on their worldwide passive income, with potential tax credits or exemptions for foreign taxes paid. Business income earned by non-residents is generally sourced to the country where the business activities are performed and may be subject to tax in that country. Tax residents, in contrast, are taxed on their worldwide business income, with potential deductions and tax credits for foreign taxes paid. There are various exceptions and exemptions to the 183-Day Rule, which can impact an individual's tax residency status and income sourcing. Some common exceptions include temporary assignments and business trips, commuters and cross-border workers, students and trainees, and diplomatic personnel and government employees. In some cases, the 183-Day Rule may not apply to individuals on temporary assignments or business trips, depending on the specific tax laws and tax treaties in place. For example, a tax treaty may exempt income earned by an employee on a temporary assignment in a foreign country from taxation, provided that the assignment lasts for less than 183 days and a foreign employer pays the employee's remuneration. Commuters and cross-border workers living in one tax jurisdiction and working in another may be subject to special rules regarding the 183-Day Rule. In some cases, these individuals may be considered tax residents of both jurisdictions, leading to potential double taxation. Tax treaties often address this issue by providing tie-breaker rules or allocating taxing rights between the two jurisdictions. Students and trainees who are temporarily present in a foreign country for educational purposes may be exempt from the 183-Day Rule, as their presence is not considered to be for the purpose of earning income. Tax treaties often contain provisions that exempt students and trainees from taxation on certain types of income, such as grants, scholarships, and allowances, as well as any income earned through part-time employment related to their studies or training. Diplomatic personnel and government employees are typically exempt from the 183-Day Rule, as their presence in a foreign country is not considered to be for the purpose of earning income. Tax treaties and domestic tax laws generally exempt these individuals from taxation on their employment income and other types of income related to their official duties. Properly calculating days of presence is essential for accurately applying the 183-Day Rule. This involves counting days of physical presence and understanding the types of excluded days. Generally, any day during which an individual is present in a tax jurisdiction, even for part of the day, is considered a day of presence for the 183-Day Rule. This includes arrival and departure days and any days spent in transit within the jurisdiction. Travel days, such as days spent on a plane, train, or ship, may also be considered days of presence for the 183-Day Rule, depending on the specific tax laws and treaties in place. In some cases, travel days may be excluded from the calculation, while in others, they may be counted as full or partial days of presence. Certain days of presence may be excluded from the 183-Day Rule calculation, depending on the specific tax laws and treaties in place. Common examples of excluded days include: Medical Emergencies: Days spent in a tax jurisdiction for medical treatment due to an emergency or unforeseen illness may be excluded from the calculation. Natural Disasters: Days spent in a tax jurisdiction due to a natural disaster, such as an earthquake, hurricane, or flood, may be excluded from the calculation. Unforeseen Circumstances: Days spent in a tax jurisdiction due to unforeseen circumstances, such as a family emergency or a canceled flight, may be excluded from the calculation. Compliance with the 183-Day Rule requires proper record-keeping, documentation, and tax filing. This involves maintaining accurate travel logs and calendars, providing proof of income and tax documents, and filing taxes under the 183-Day Rule. Individuals subject to the 183-Day Rule should maintain accurate travel logs and calendars to track their days of presence in various tax jurisdictions. These logs and calendars should include details such as arrival and departure dates, the purpose of each trip, and any relevant documentation, such as plane tickets, hotel reservations, and conference registrations. Individuals should also retain documentation related to their income and tax payments, such as payslips, bank statements, tax forms, and receipts for tax payments. This documentation is essential for proving income sourcing and ensuring compliance with the 183-Day Rule. When filing taxes, individuals must report their income and deductions according to their tax residency status and the 183-Day Rule. This may involve reporting worldwide income for tax residents or only reporting income sourced from the tax jurisdiction for non-residents. Individuals subject to taxation in multiple jurisdictions due to the 183-Day Rule may be eligible for tax credits or relief to prevent double taxation. Tax treaties and domestic tax laws often provide mechanisms for claiming foreign tax credits or deductions for foreign taxes paid, ensuring that individuals are not taxed twice on the same income. The 183-Day Rule is a principle used by tax authorities worldwide to determine tax residency. It states that individuals spending more than 183 days in a tax jurisdiction during a tax year are considered tax residents. This rule helps determine tax obligations, as residents are taxed on worldwide income, while non-residents are only taxed on income sourced from the jurisdiction. The rule originated in the Model Tax Convention developed by the OECD and has been adopted by many countries. Determining tax residency using the 183-Day Rule involves physical presence and substantial presence tests. Tax implications differ for residents and non-residents, with residents subject to taxation on worldwide income. Tax treaties play a significant role in applying the rule and can modify its application. The 183-Day Rule also affects income sourcing, particularly for employment, passive income, and business income. There are exceptions and exemptions to the rule, such as for temporary assignments, commuters, students, and diplomatic personnel. Properly calculating days of presence and complying with the rule requires accurate record-keeping, documentation, and tax filing.What Is the 183-Day Rule?

History of the 183-Day Rule

183-Day Rule and Tax Residency

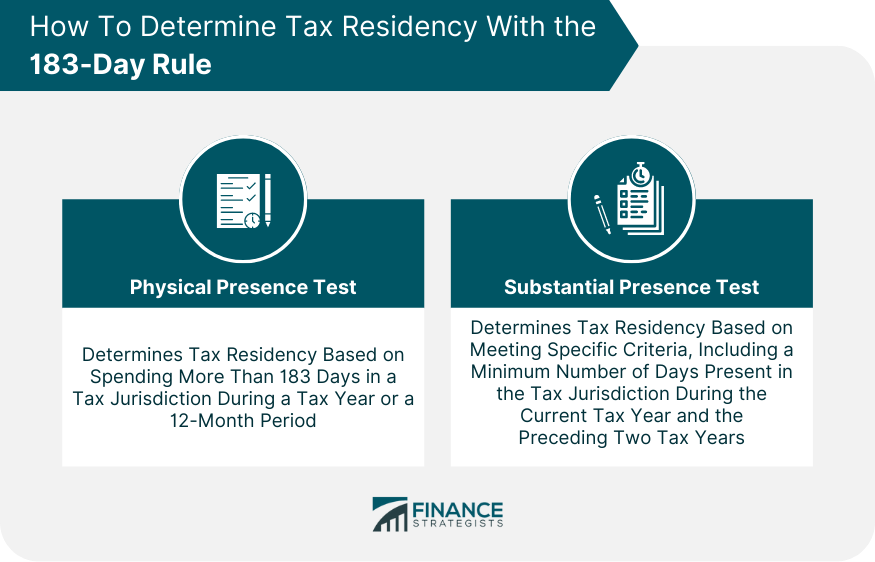

Determining Tax Residency With the 183-Day Rule

Physical Presence Test

Substantial Presence Test

Tax Implications for Residents and Non-Residents

Tax Treaties and the 183-Day Rule

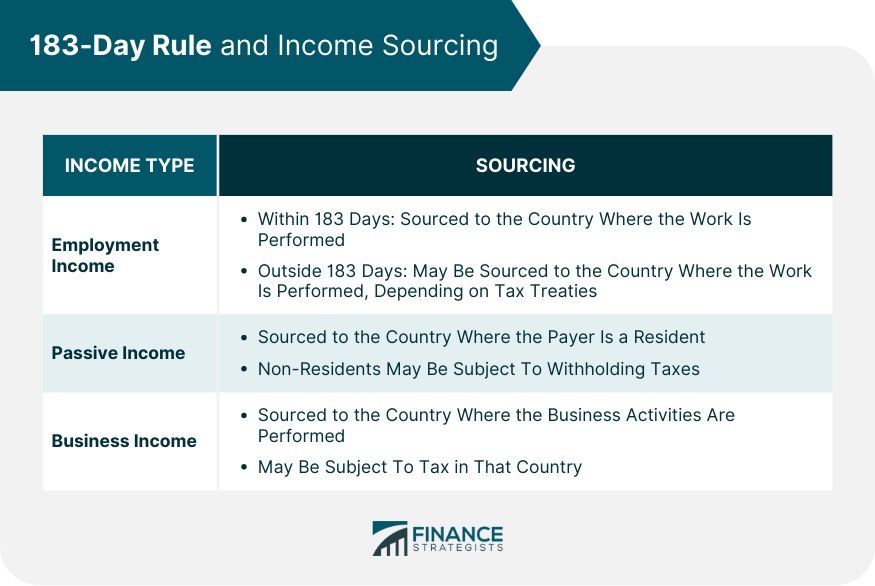

183-Day Rule and Income Sourcing

Sourcing of Employment Income

Income Earned Within the 183-Day Period

Income Earned Outside the 183-Day Period

Sourcing of Other Types of Income

Passive Income

Business Income

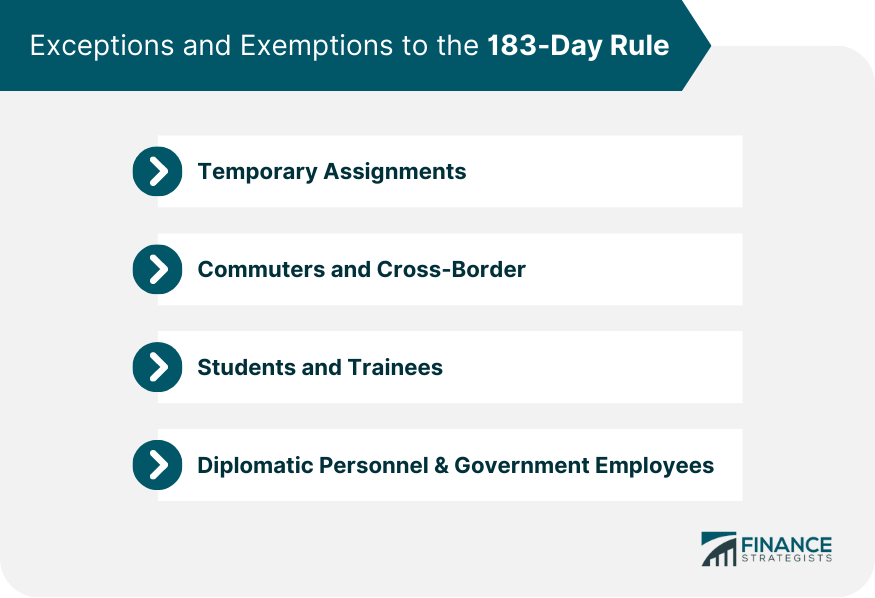

Exceptions and Exemptions to the 183-Day Rule

Temporary Assignments and Business Trips

Commuters and Cross-Border Workers

Students and Trainees

Diplomatic Personnel and Government Employees

Calculating Days of Presence for the 183-Day Rule

Counting Days of Physical Presence

Full Days vs Part Days

Travel Days

Excluded Days of Presence

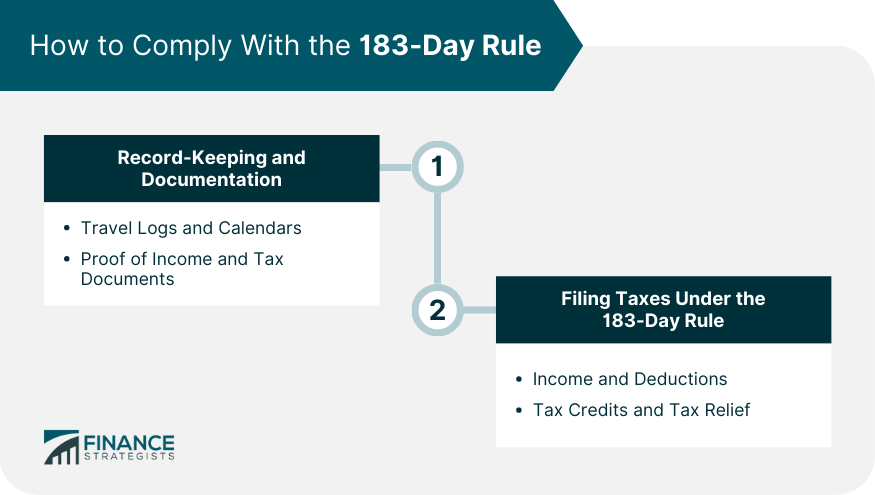

How to Comply With the 183-Day Rule

Record-Keeping and Documentation

Travel Logs and Calendars

Proof of Income and Tax Documents

Filing Taxes Under the 183-Day Rule

Income and Deductions

Tax Credits and Tax Relief

Conclusion

183-Day Rule FAQs

The 183-Day Rule is a tax guideline determining a person's tax residency status in a given country. If a person spends more than 183 days in a country within a tax year, they may be considered a tax resident of that country and could be subject to local tax laws.

If you spend more than 183 days in a country during a tax year, you may be considered a tax resident of that country and may be required to pay taxes there. This could affect your tax obligations in your home country as well. It's important to understand the specific tax laws of both countries to avoid double taxation or non-compliance.

No, the 183-Day Rule does not apply universally. Each country has its own tax laws and residency rules. Some use the 183-Day Rule, while others may use different criteria. Always check the specific tax laws of the country you are in or plan to stay in for an extended period.

The application of the 183-Day Rule can vary by country. Some countries count the 183 days within a single calendar year, while others may consider a rolling 12-month period. It's important to check the specific rules of the country in question.

If you spend more than 183 days in a country where the 183-Day Rule applies, you may become a tax resident of that country and be liable for taxes there. If you do not comply with the tax laws, you could face penalties, including fines and interest. Understanding and complying with the tax laws of any country where you spend significant time is crucial.

True Tamplin is a published author, public speaker, CEO of UpDigital, and founder of Finance Strategists.

True is a Certified Educator in Personal Finance (CEPF®), author of The Handy Financial Ratios Guide, a member of the Society for Advancing Business Editing and Writing, contributes to his financial education site, Finance Strategists, and has spoken to various financial communities such as the CFA Institute, as well as university students like his Alma mater, Biola University, where he received a bachelor of science in business and data analytics.

To learn more about True, visit his personal website or view his author profiles on Amazon, Nasdaq and Forbes.