What Is Capital Gains Tax on a Deceased Estate?

Capital Gains Tax (CGT) on a deceased estate refers to the tax levied on the gain realized from the disposal of assets belonging to a deceased individual. Upon death, it is generally deemed that a person disposes of their assets, which may potentially trigger a CGT event.

The tax is generally based on the market value of the assets at the time of the individual's death. The purpose of CGT in this context is to ensure the fair taxation of income derived from the disposal of assets that have appreciated in value.

It's important for the executor of the estate and beneficiaries to understand this tax as it can significantly impact the net value of the inheritance and must be appropriately reported and paid to avoid legal complications.

Immediate Implications of Death on Capital Gains Tax

Upon death, the law deems that a person had disposed of their assets just before their death, even though no actual disposal took place.

This triggers a CGT event. The assets' market value at the time of the deceased's death determines the capital gain or loss. However, this does not mean that the estate or beneficiaries will automatically owe tax.

If the deceased person acquired the asset after 20 September 1985, there are specific rules that apply to the deceased estate.

Determining the Base Cost for CGT Purposes

Establishing the base cost for CGT purposes can be complex. It often involves historical data, such as the original purchase price and costs associated with acquiring or improving the asset.

If the deceased acquired the asset before 20 September 1985 (pre-CGT), then the base cost for CGT purposes is usually the market value of the asset on the date of death.

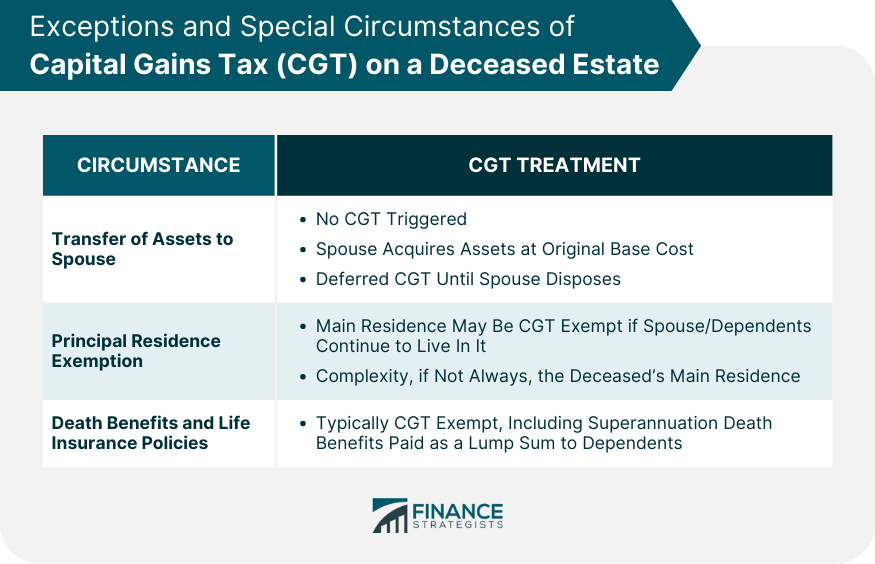

Exceptions and Special Circumstances

There are several circumstances where the normal rules for CGT and deceased estates do not apply. Understanding these exceptions can help estates and beneficiaries navigate their tax obligations more effectively.

Transfer of Assets to Spouse

Generally, a deceased estate can transfer assets to a spouse without triggering a CGT event. The spouse is considered to have acquired the assets at the deceased's original base cost, and any capital gain or loss will be deferred until the spouse disposes of the assets.

Principal Residence Exemption

The deceased's main residence can sometimes be exempt from CGT, particularly if the spouse or dependents continue to live in it. However, the application of this exemption can be complex, especially if the property was not always the deceased's main residence.

Death Benefits and Life Insurance Policies

Typically, life insurance policies and death benefits are exempt from CGT. This also applies to superannuation death benefits, provided they are paid out as a lump sum to the deceased's dependents.

Disposal of Assets From a Deceased Estate

The executor of the deceased estate usually handles the disposal of the deceased's assets. This process can impact the calculation and payment of CGT.

Role of the Executor and Beneficiaries

The executor is responsible for managing the deceased's assets, including the disposal of those assets. However, once the assets have been distributed to the beneficiaries, they are responsible for any CGT if and when they decide to sell.

Calculation of Capital Gains or Loss

Calculating capital gains or losses involves subtracting the asset's base cost from the selling price. The executor or beneficiaries can also deduct certain costs related to disposing of the asset.

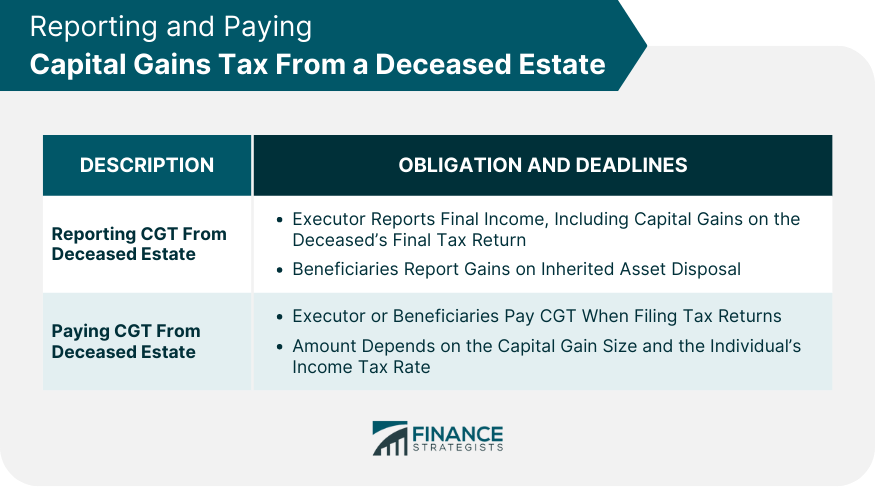

Reporting and Paying Capital Gains Tax From a Deceased Estate

The process of reporting and paying CGT from a deceased estate must comply with the tax laws and deadlines.

Obligation and Deadlines

The executor must report the deceased's final income, including any capital gains or losses, on the deceased's final income tax return. The beneficiaries must report any capital gains or losses they make when they dispose of the inherited assets.

Filing and Paying Process

The executor or beneficiaries must pay any CGT owed when they lodge their tax returns. The amount of tax payable depends on various factors, such as the size of the capital gain and the individual's income tax rate.

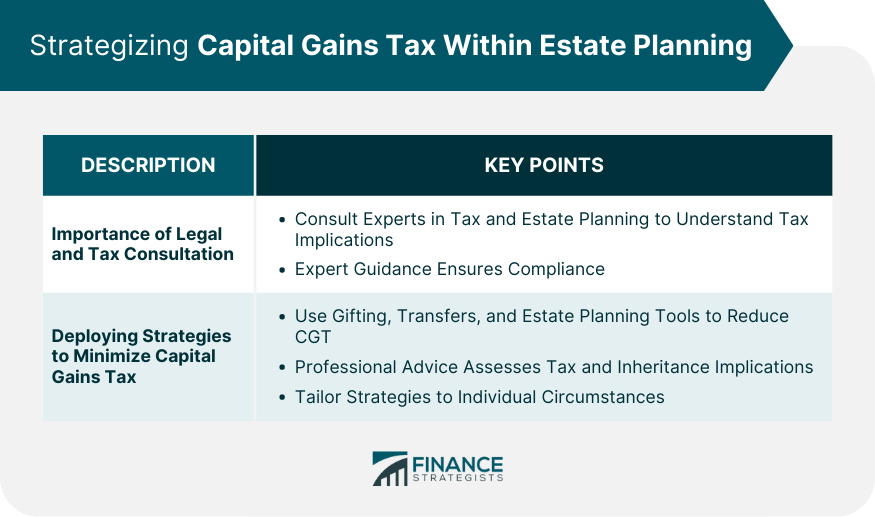

Strategizing Capital Gains Tax Within Estate Planning

Thoughtfully CGT within the broader framework of estate planning can significantly lessen tax liabilities and provide a seamless transition of assets.

By being proactive and creating a well-rounded plan, individuals can potentially save a considerable amount of money and prevent unanticipated tax consequences for beneficiaries.

Importance of Legal and Tax Consultation

Consulting with professionals specializing in tax and estate planning is crucial when addressing potential tax liabilities.

These experts not only help individuals comprehend their current tax standing but also forecast potential future implications, which can greatly aid in informed decision-making.

They are trained to understand the intricate nuances of tax law, making their guidance invaluable when navigating complex tax matters.

Their advice can also help safeguard against potential errors or oversights, ensuring compliance with all tax obligations and reducing the risk of legal issues down the line.

Deploying Strategies to Minimize Capital Gains Tax

A variety of strategies, such as gifts, transfers, or other estate planning tools, can be employed to potentially minimize CGT. However, it's worth noting that these strategies come with their own set of tax implications.

For instance, while gifting assets may minimize CGT, it could have inheritance tax implications. Hence, professional advice is pivotal to understanding these implications and formulating a strategy that minimizes the overall tax burden while ensuring legal compliance.

The most effective strategies are often tailored to individual circumstances, taking into account factors such as the type and value of assets, the beneficiaries' situations, and the future financial landscape.

Bottom Line

Capital Gains Tax on a deceased estate, which arises from the perceived disposal of assets at the time of an individual's death, can significantly impact the net value of an inheritance.

Key considerations in this context involve understanding the base cost of assets for CGT purposes, recognizing special circumstances and exceptions, and the roles and responsibilities of executors and beneficiaries.

Effectively managing this tax liability requires thoughtful estate planning and professional guidance to navigate complex tax laws.

Strategies like gifts and transfers can potentially minimize CGT, but these also come with their own implications and must be strategically implemented.

Ultimately, the comprehensive understanding and effective management of CGT within estate planning can save significant money, prevent unforeseen tax complications for beneficiaries, and ensure a seamless transition of assets.

Capital Gains Tax on a Deceased Estate FAQs

When a person passes away, it is deemed that they have disposed of their assets just before death, triggering a capital gains tax event. However, this doesn't mean that the estate or beneficiaries will automatically owe tax. The tax treatment depends on the nature of the asset, its value at the time of death, and who inherits it.

The base cost for CGT purposes depends on when the deceased acquired the asset. If the asset was acquired after 20 September 1985, the original cost base is used. If it was acquired before that date (pre-CGT), the base cost is usually the market value of the asset on the date of death.

Yes, there are exceptions. For instance, a transfer of assets to a spouse does not usually trigger a CGT event. Also, the principal residence exemption may apply if the property was the deceased's main residence. Life insurance policies and death benefits are generally exempt from CGT.

The executor of the estate is responsible for paying any CGT owed at the time of death and reporting it on the deceased's final tax return. Once assets have been distributed, the beneficiaries become responsible for any capital gains tax owed when they dispose of their inherited assets.

There are several strategies to minimize CGT, including gifting or transferring assets, utilizing tax exemptions, and considering the timing of asset sales. However, each strategy has different tax implications, so it's always recommended to seek professional advice when planning for estate tax.

True Tamplin is a published author, public speaker, CEO of UpDigital, and founder of Finance Strategists.

True is a Certified Educator in Personal Finance (CEPF®), author of The Handy Financial Ratios Guide, a member of the Society for Advancing Business Editing and Writing, contributes to his financial education site, Finance Strategists, and has spoken to various financial communities such as the CFA Institute, as well as university students like his Alma mater, Biola University, where he received a bachelor of science in business and data analytics.

To learn more about True, visit his personal website or view his author profiles on Amazon, Nasdaq and Forbes.