Capital gains, which arise from the sale of investments or property, play a crucial role in determining an individual's Adjusted Gross Income (AGI). In the U.S. tax system, capital gains are classified into short-term and long-term, depending on the duration of ownership. Short-term gains, from assets held for less than one year, are taxed at ordinary income tax rates, thereby directly influencing AGI. Long-term gains, from assets held for more than a year, benefit from preferential rates, which are typically lower than ordinary income tax rates. While both short-term and long-term gains add to one's total income, only net gains – after offsetting losses – contribute to AGI. A higher AGI can influence the deductibility of certain expenses and phase out of specific tax credits, possibly leading to a higher overall tax liability. Capital gains arise when an asset—like a stock, bond, or a piece of real estate—is sold for a price higher than its purchase price. The difference between the selling price and the purchase price is considered a capital gain. It's a fundamental concept in the world of investing and tax planning. Definition: Profits or gains realized from the sale of assets that were held for one year or less are considered short-term capital gains. Tax Implications: Typically, short-term capital gains are taxed at your ordinary income tax rate. This can be higher than the tax rate for long-term capital gains. Examples: If you buy shares of a company in January and sell them in December of the same year at a profit, the profit would be considered a short-term capital gain. Definition: Profits or gains made from selling assets that were held for more than one year before the sale are classified as long-term capital gains. Tax Implications: In many jurisdictions, long-term capital gains benefit from favorable tax rates compared to short-term capital gains. This tax advantage is designed to encourage long-term investing. Examples: If you buy a piece of property and sell it after holding onto it for three years at a profit, that profit would be considered a long-term capital gain. The tax rate on capital gains depends on the nature of the gain (short-term or long-term) and the taxpayer's overall income level. Short-term capital gains are generally taxed at the individual's ordinary income tax rate, which can be as high as 37%. On the other hand, long-term capital gains have preferential tax rates. As of my last training data, they were taxed at 0%, 15%, or 20%, depending on the individual's taxable income. These rates provide an incentive for investors to hold onto assets longer, to benefit from lower tax rates. AGI is a key measure used in the US tax system. It's the basis for many of the calculations used when preparing your tax return, including your eligibility for many tax credits and deductions. In essence, AGI is your gross income— which includes wages, interest, dividends, and other income— minus certain adjustments. These adjustments can include things like student loan interest, alimony payments, contributions to certain retirement accounts, and more. Calculating AGI begins by adding up all of your earned income for the year. This includes wages from your job, any self-employment income, income from rental properties, dividends, interest, and capital gains. From this total income, you subtract allowable deductions—these are the "adjustments" that make AGI "adjusted." These can include things like educator expenses, health savings account deductions, certain business expenses, and others. The result is your AGI. AGI plays a pivotal role in tax planning because it can affect the ability to claim many common deductions and credits. Lowering your AGI can potentially reduce your tax liability, qualify you for tax credits, or increase the amount you can claim for certain tax deductions. Capital gains play a crucial role in determining AGI. The net capital gain (or loss) from the sale of assets during the year—whether short-term or long-term—gets factored into the income side of the AGI calculation. Thus, a large capital gain can significantly increase your AGI. As mentioned earlier, the tax rate on long-term capital gains depends on taxable income, which is derived from your AGI. Higher AGI can push you into a higher tax bracket, which in turn can lead to a higher tax rate on your long-term capital gains. One of the most effective tax planning strategies involves leveraging your AGI to minimize capital gains tax. If you can reduce your AGI through deductions, you may end up in a lower tax bracket for capital gains. For instance, if your AGI falls in the 15% bracket for long-term capital gains, you pay 0% on these gains. That's a significant tax saving. Another strategy is timing when you recognize capital gains and losses. If you anticipate a significant capital gain from selling an asset, consider also selling a poorly performing asset in the same year. This could offset the gain and potentially reduce your AGI. Contributions to traditional retirement accounts like a traditional IRA or 401(k) can reduce your AGI. The money you put into these accounts is generally deducted from your income for the year, lowering your AGI and potentially reducing your capital gains tax liability. Similarly, other deductions like Health Savings Accounts (HSAs), alimony payments, or student loan interest can also help reduce your AGI and therefore minimize your tax liability. In understanding the intricate relationship between Capital Gains and Adjusted Gross Income (AGI), it's clear that effective tax planning can result in substantial savings. Capital gains, stemming from the profit made on the sale of assets, directly influence AGI, which is a foundational measure in the U.S. tax system. The nature of these gains—whether short-term or long-term—has different tax implications, with the latter enjoying preferential rates. AGI, on the other hand, is the total of one's income minus specific adjustments. It serves as the backbone for tax calculations, credits, and deductions. Notably, the interplay between capital gains and AGI highlights the significance of strategic planning. By managing one's AGI—through tactics like timing asset sales or utilizing specific deductions—taxpayers can potentially minimize their capital gains tax liability. If you're seeking tailored strategies for optimizing your financial position, consider seeking professional tax planning services.Overview of Capital Gains and Adjusted Gross Income (AGI)

Understanding Capital Gains

What Are Capital Gains?

Types of Capital Gains

Short-Term Capital Gains

Long-Term Capital Gains

Tax Rates on Capital Gains

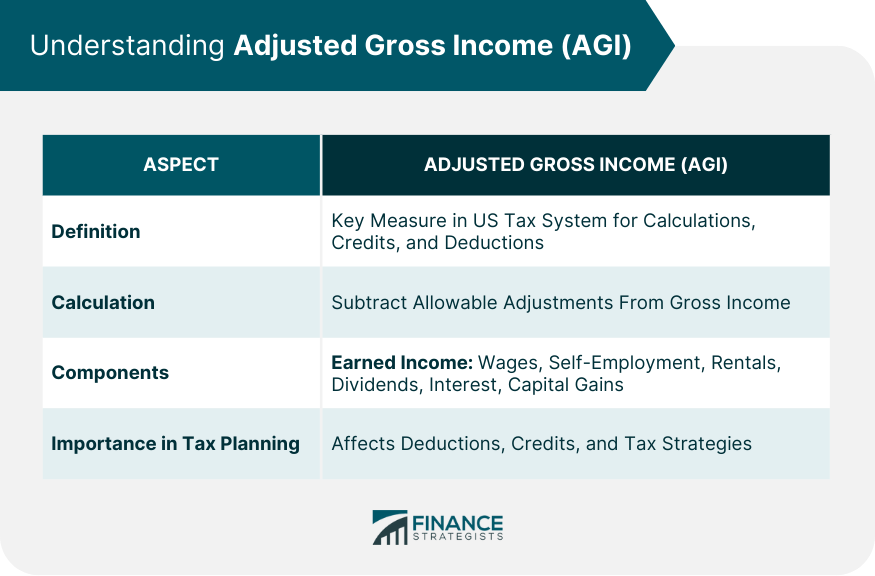

Understanding Adjusted Gross Income (AGI)

What Is Adjusted Gross Income (AGI)?

How Is AGI Calculated?

Role of AGI in Tax Planning

Interplay Between Capital Gains and AGI

How Capital Gains Contribute to AGI

How AGI Affects Capital Gains Tax Rate

Tax Planning Strategies

Leveraging AGI to Minimize Capital Gains Tax

Timing Capital Gains and Losses

Utilizing Retirement Contributions and Other Deductions to Reduce AGI

Bottom Line

Understanding Capital Gains and Adjusted Gross Income FAQs

Capital gains occur when you sell an asset for more than its purchase price. These gains contribute to your Adjusted Gross Income (AGI) and can affect your tax rate.

AGI is your total income minus certain deductions. It's key in tax planning as it affects your eligibility for many tax credits and deductions.

By reducing your AGI through deductions, you may lower your tax bracket for capital gains, thus potentially minimizing capital gains tax.

Contributions to traditional retirement accounts can lower your AGI, as the money you contribute is generally deducted from your income for the year.

Timing when you recognize capital gains and losses can impact your AGI. For example, selling a poorly performing asset can offset a gain and potentially reduce your AGI.

True Tamplin is a published author, public speaker, CEO of UpDigital, and founder of Finance Strategists.

True is a Certified Educator in Personal Finance (CEPF®), author of The Handy Financial Ratios Guide, a member of the Society for Advancing Business Editing and Writing, contributes to his financial education site, Finance Strategists, and has spoken to various financial communities such as the CFA Institute, as well as university students like his Alma mater, Biola University, where he received a bachelor of science in business and data analytics.

To learn more about True, visit his personal website or view his author profiles on Amazon, Nasdaq and Forbes.