A value-add tax is a tax charged on the gross profit of every step in the supply chain. It's best understood using an example: The country of Decivat has a 10% value added tax. A flour manufacturer will buy $1,000 worth of grain from a farmer for $1,100, $100 of which will go to the government as VAT, to create flour. If the manufacturer sells the flour to a baker for $1,500, he will charge $1,550 since a 10% VAT is imposed on the gross profit of $500. A value-added tax is the most common form of consumption tax for industrialized countries with over 160 countries levying a VAT, excluding the United States. VAT is intricate in its workings, but at its core, it's a multi-stage tax. Businesses collect the tax on behalf of the government: when they buy goods or services, they are charged VAT, and when they sell goods or services, they charge VAT. The idea is to tax the value addition at each transaction stage. At the end of the tax period, businesses can offset their VAT liabilities with the VAT they've paid to suppliers. The difference is then remitted to the tax authorities or claimed as a refund. As governments scuttle to fund increasing budgetary demands, VAT emerges as a lucrative revenue source. It's broad-based, applying to a wide range of goods and services. This widespread applicability often results in significant revenue, especially in countries with robust consumption patterns. While direct taxes can be evaded, it's harder to dodge an indirect tax like VAT, as it's built into every transaction. One of the core tenets of a good tax system is neutrality, where the tax does not distort economic choices. VAT is designed to be neutral and equitable. Since it is a consumption-based tax, it doesn't discriminate between different types of businesses, ensuring that all businesses are on an equal footing, regardless of their size or the nature of their operations. The concept of tax shifting revolves around the ability to pass the tax burden down the supply chain until it finally reaches the consumer. With VAT, businesses act as tax collectors, but it's the end consumer who bears the brunt of the tax. This system ensures that the tax is collected efficiently while making sure businesses aren't unduly burdened. Setting the VAT rate is a critical decision, striking a balance between revenue generation and economic impact. Often, countries will employ multiple rates. A standard rate for most goods and services, reduced rates for certain categories, and zero rates for others. Factors considered include national budgetary needs, economic conditions, and the need for social equity. Not all goods and services are subject to VAT. Essentials like food, medicine, and education might be exempted or zero-rated to ensure that the tax doesn't disproportionately burden the less affluent. Furthermore, small businesses with turnovers below specific thresholds might be exempted to promote entrepreneurship and reduce administrative burdens. VAT's effectiveness hinges on its efficient collection and administration. Modern tax administrations use digital platforms for VAT registrations, filings, and payments. Automation ensures compliance, reduces errors, and allows for real-time data analysis. Effective administration also includes regular audits and robust penalty systems for non-compliance. Advocates of the tax claim the following: VAT does not penalize wealth generation or profitability, unlike corporate or income taxes. It's based on consumption, ensuring that those who consume more, pay more. Thus, it promotes business growth and entrepreneurial activities, while still ensuring significant revenue. It helps raise government revenues without punishing wealth or success (like income tax). With VAT, the tax is applied uniformly at each stage of production, making it difficult for businesses to evade or avoid the tax, ensuring a consistent revenue stream for governments. Replacing other taxes with a VAT would close tax loopholes. Since VAT is levied on consumption and not income, it indirectly promotes saving. If people choose to save rather than spend, they aren't taxed. This can lead to increased investments and a healthier economy in the long run. It is based on consumption and therefore encourages saving. Those against a VAT argue the following: If the same rate applies to both luxury items and necessities, it can disproportionately burden lower-income groups, as they spend a higher percentage of their income on consumption. A VAT would be felt less by the wealthy as lower-income earners would pay a higher percentage of their earnings in taxes with a VAT system. While VAT might be designed to be borne by the end consumer, businesses often grapple with increased administrative costs. Tracking, collecting, and remitting the tax requires resources, and smaller businesses, in particular, might find this challenging. A VAT creates higher costs for businesses. In countries with federal structures, implementing a uniform VAT can sometimes limit the ability of states or provinces to set their own tax rates based on regional needs. This can lead to conflicts and requires careful legislative crafting to ensure all regions' needs are considered. Local governments are unable to set localized tax rates. Value-Added Tax (VAT) is a multi-stage tax levied on the gross profit at each step of the supply chain. It acts as a significant revenue source for governments, broad-based and difficult to evade, ensuring consistent revenue generation. VAT's neutrality makes it equitable for all businesses, promoting economic choices without distortion. By shifting the tax burden to end consumers, businesses act as efficient tax collectors. Countries employ varying rates and exemptions to strike a balance between revenue needs and social equity. Modern tax administrations leverage digital platforms for efficient VAT collection and administration. Advocates highlight VAT's advantages, such as revenue generation without penalizing wealth, closing tax loopholes, and indirectly encouraging saving. However, critics argue that its uniform application can burden lower-income groups, and businesses may face increased administrative costs. Additionally, in federal structures, limited local tax rate autonomy can be a challenge.VAT Definition

How Does Value-Added Tax (VAT) Work

Purpose of Value-Added Tax (VAT)

Revenue Generation

Neutral Taxation

Tax Shifting

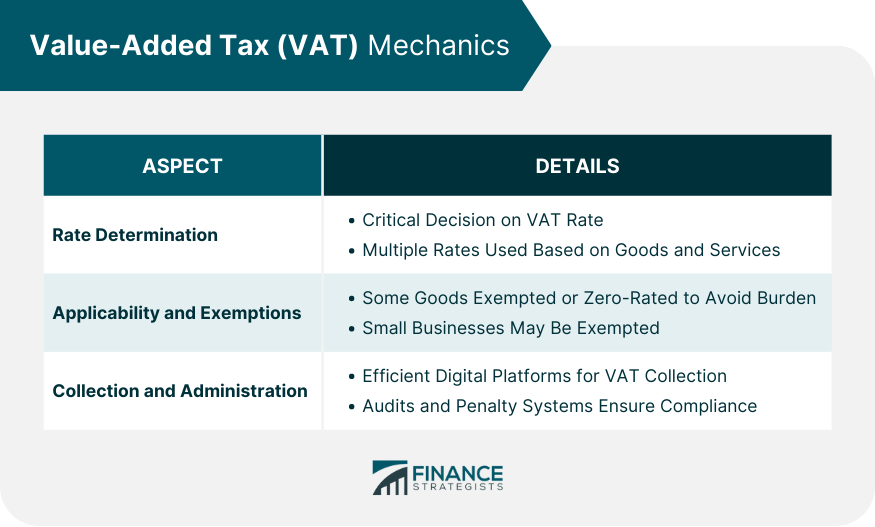

Value-Added Tax (VAT) Mechanics

Rate Determination

Applicability and Exemptions

Collection and Administration

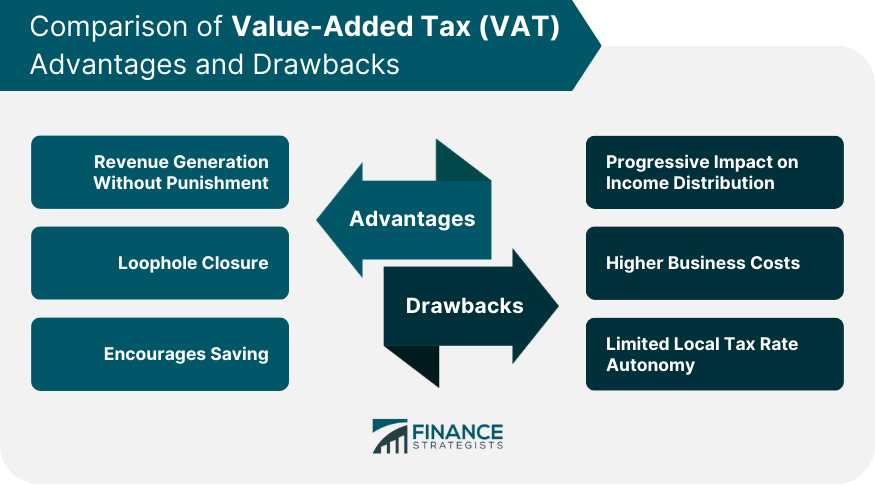

VAT Advantages

Revenue Generation Without Punishment

Loophole Closure

Encourages Saving

VAT Drawbacks

Progressive Impact on Income Distribution

Higher Business Costs

Limited Local Tax Rate Autonomy

Conclusion

Value-Added Tax (VAT) FAQs

VAT stands for Value-Added Tax.

A value-added tax is a tax charged on the gross profit of every step in the supply chain.

Advocates of the VAT claim that it helps raise government revenues without punishing wealth or success. Replacing other taxes with a VAT would close tax loopholes. It is based on consumption and therefore encourages saving.

Those against a VAT argue that it would be felt less by the wealthy as lower-income earners would pay a higher percentage of their earnings in taxes. A VAT creates higher costs for businesses, while preventing local governments from setting localized tax rates.

A VAT system is found in many European countries, but the U.S. does not utilize it.

True Tamplin is a published author, public speaker, CEO of UpDigital, and founder of Finance Strategists.

True is a Certified Educator in Personal Finance (CEPF®), author of The Handy Financial Ratios Guide, a member of the Society for Advancing Business Editing and Writing, contributes to his financial education site, Finance Strategists, and has spoken to various financial communities such as the CFA Institute, as well as university students like his Alma mater, Biola University, where he received a bachelor of science in business and data analytics.

To learn more about True, visit his personal website or view his author profiles on Amazon, Nasdaq and Forbes.