Yield refers to the income generated by an investment over a period of time, expressed as a percentage of the invested amount, market value, or face value of the security. It includes both interest earned, such as from bonds, and dividends received, such as from stocks. This income can be in the form of dividends for stocks, or interest for bonds and other fixed-income securities. Yield essentially quantifies the earnings generated and realized on an investment relative to its price. One of the primary purposes of assessing yield is to evaluate the potential returns of various investments. By comparing yields, an investor can make informed decisions about where to allocate funds. For instance, if two bonds offer the same level of risk but different yields, the one with the higher yield may be more appealing, assuming other factors are constant. Yield serves as a standard metric that can be used to compare different financial instruments, whether it's stocks, bonds, or real estate investments. By examining the yield, investors can gauge the effectiveness of their investment and determine which assets are providing the best income relative to their price. Understanding yield is crucial for balancing risk and return. Typically, higher yields might suggest higher risks. However, by diversifying investments across varying yields, investors can aim to optimize returns while managing potential downsides. Current yield is a measure that relates the annual income from an investment to its current market price. For bonds, it's calculated by dividing the annual interest payment by the bond's current market price. It provides investors with a snapshot of the income they might expect relative to the asset's market value at a specific point in time. YTM represents the total return anticipated on a bond if it's held until it matures. This calculation takes into account the bond's current market price, par value, coupon interest rate, and the number of years remaining to maturity. It's a comprehensive measure, offering a long-term view of a bond's potential return. YTC is particularly relevant for callable bonds, which are bonds that can be redeemed by the issuer before they mature. It estimates the return on a bond if it's called, or bought back, before its official maturity date. This metric is crucial for understanding potential returns in scenarios where the issuer might opt to buy back the bond. YTW is a conservative measure that provides the lowest potential yield out of all possible redemption scenarios, whether it's maturity, call, or even other events. It gives investors a "worst-case scenario" perspective, allowing for informed decisions based on the least favorable conditions. YOC calculates the dividend yield of an investment based on the original cost, rather than its current market price. It offers insights into the performance of an investment over time, reflecting the income generated relative to the initial outlay. Yield represents the cash flow an investor receives from an investment in a security, typically calculated annually, but occasionally using variations like quarterly or monthly yields. While the basic premise revolves around understanding returns relative to price or investment, different yields require different considerations, from time horizons to potential call dates. Yield can be calculated using the following formula: For example, say that an investor buys a stock for $100. After holding it for a period of time, the investor earns $5 in dividends and sells the stock for $120. The realized returns are equal to the earned dividends plus the appreciation in share price, or ($5 + $20) / $100 = 25%. Interest rates, often set by central banks, have a significant influence on yields. When interest rates rise, bond prices typically fall, leading to higher yields. Conversely, when interest rates drop, bond prices often rise, resulting in lower yields. The relationship between interest rates and yield is pivotal for bond market dynamics. The price of bonds is inversely related to yield. As bond prices increase, yield decreases and vice-versa. Factors such as changes in issuer creditworthiness, bond demand and supply, and market speculation can influence bond prices and, subsequently, yields. General market conditions, driven by global events, economic indicators, or geopolitical developments, can sway investor sentiment and impact yields. In tumultuous times, investors might flock to safer assets, pushing yields down, while in bullish markets, they might seek riskier assets, affecting yields differently. The creditworthiness of a bond issuer plays a crucial role in determining yield. Bonds from issuers with higher credit risks tend to offer higher yields to compensate for the increased risk. Credit rating agencies often provide ratings that investors use to assess this risk and the associated yield. The broader economic landscape, from inflation rates to employment figures, can influence yields. For instance, during economic downturns, central banks might lower interest rates to stimulate borrowing, which can push yields down. Certain investment vehicles, like high-yield bonds or dividend-paying stocks, can potentially boost overall yield. While they might carry higher risks, they offer opportunities for increased income generation. By reinvesting dividends or interest payments, investors can benefit from the power of compounding, leading to enhanced yields over time. Instead of taking out the income, plowing it back into the investment can lead to exponential growth. Bond laddering involves buying multiple bonds with different maturity dates. This strategy provides both short-term income and the potential for reinvestment, optimizing yield, especially in fluctuating interest rate environments. By shifting investments between sectors based on market cycles and economic conditions, investors can seek out higher-yielding opportunities. Different sectors may outperform at various times, offering varied yield potentials. A high yield might be enticing, but it could also be a trap. Sometimes, a high yield is a result of plummeting prices due to underlying issues with the investment. Chasing such yields can lead to significant losses. In the quest for higher yields, investors might overlook the fundamentals of an investment. A comprehensive analysis, beyond just the yield, is essential to ensure the investment is sound. High-yield investments often come with increased exposure to market volatility. While they might offer attractive returns, they can also be more susceptible to market swings, leading to potential capital losses. While a high yield means greater returns for investors, it must be interpreted carefully. For example, a sudden increase in the yield of stock could indicate a falling stock price. This decreases the denominator in the yield equation and so raises the resulting percentage. An increased yield can also result from an increase in dividend payments. If this does not correspond to an increase in cash flow, the issuing company may have difficulty maintaining future payments. Likewise, since bonds carry with them the risk of default, a higher than average yield could be because of a higher than average risk. Many companies that issue risky bonds also issue them with a high yield, or coupon rate, in order to increase the appeal to risk-averse investors. Yield encapsulates the income generated from investments, expressed as a percentage of the invested amount or security's value. It encompasses dividends for stocks and interest for bonds, quantifying returns relative to price. Yield is pivotal in evaluating investment opportunities, enabling comparisons across financial instruments, and managing risk and return. Its types include Current Yield, YTM, YTC, YTW, and YOC, each offering distinct insights into investment performance. Factors like interest rates, bond prices, market conditions, credit risk, and the economic environment influence yield. Strategies to enhance yield involve investment selection, reinvestment, bond laddering, and sector rotation. While enticing, chasing high yields poses risks, such as yield traps and market volatility. High yield demands caution, as it could signify underlying issues or higher risk. A comprehensive assessment beyond yield is vital for informed investment decisions.What Is Yield?

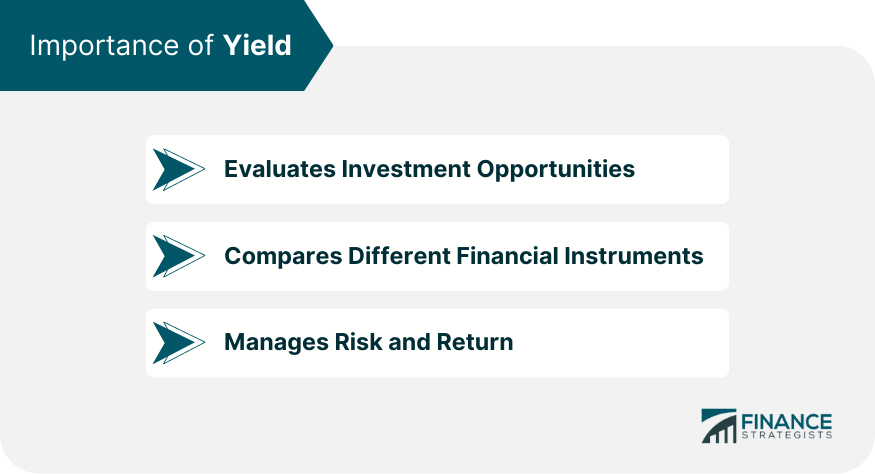

Importance of Yield

Evaluates Investment Opportunities

Compares Different Financial Instruments

Manages Risk and Return

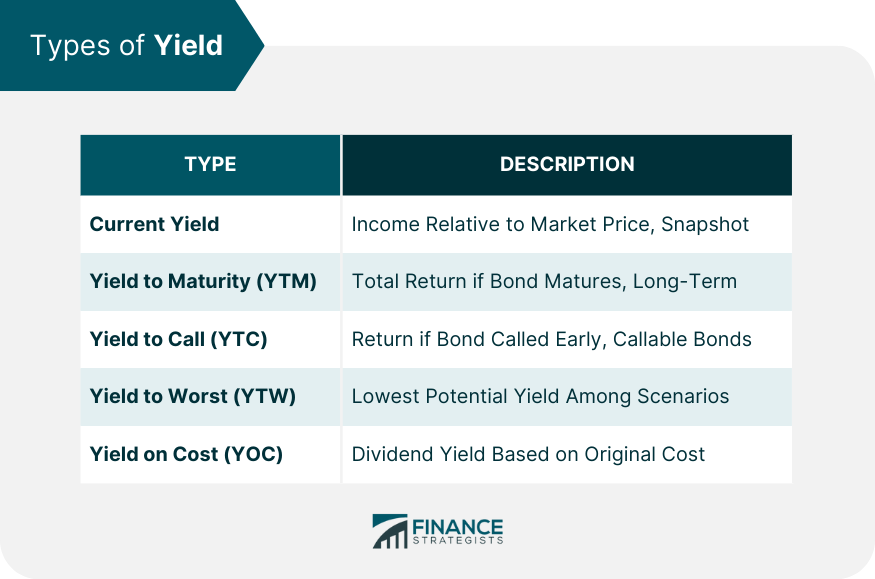

Types of Yield

Current Yield

Yield to Maturity (YTM)

Yield to Call (YTC)

Yield to Worst (YTW)

Yield on Cost (YOC)

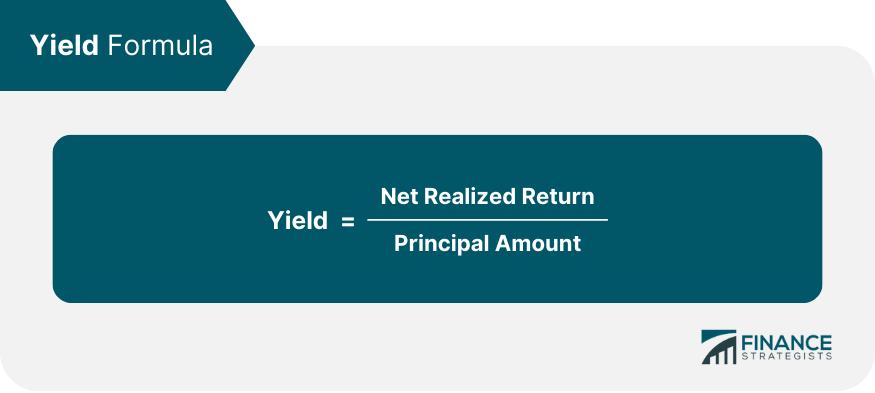

Formula for Yield

Example of Yield

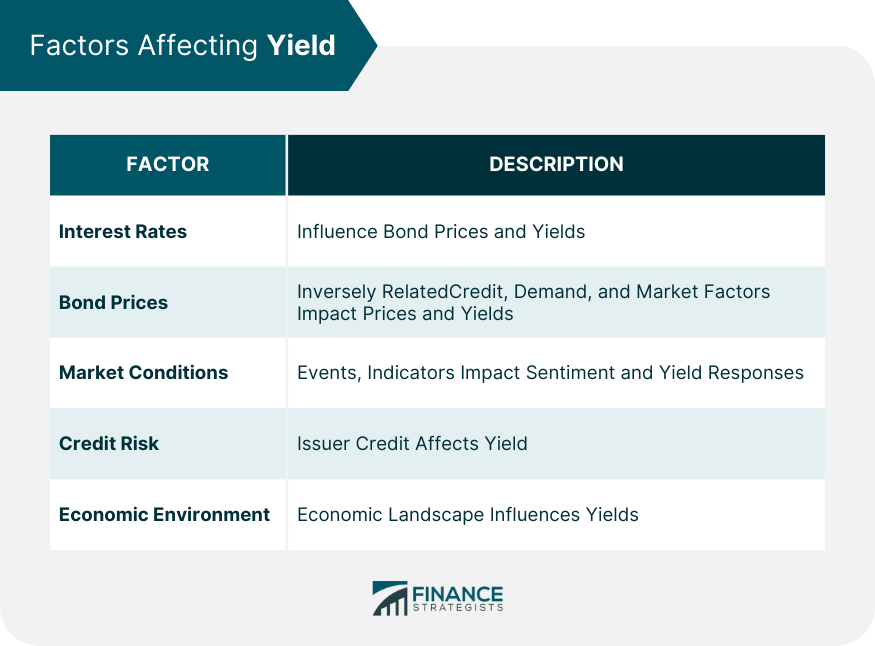

Factors Affecting Yield

Interest Rates

Bond Prices

Market Conditions

Credit Risk

Economic Environment

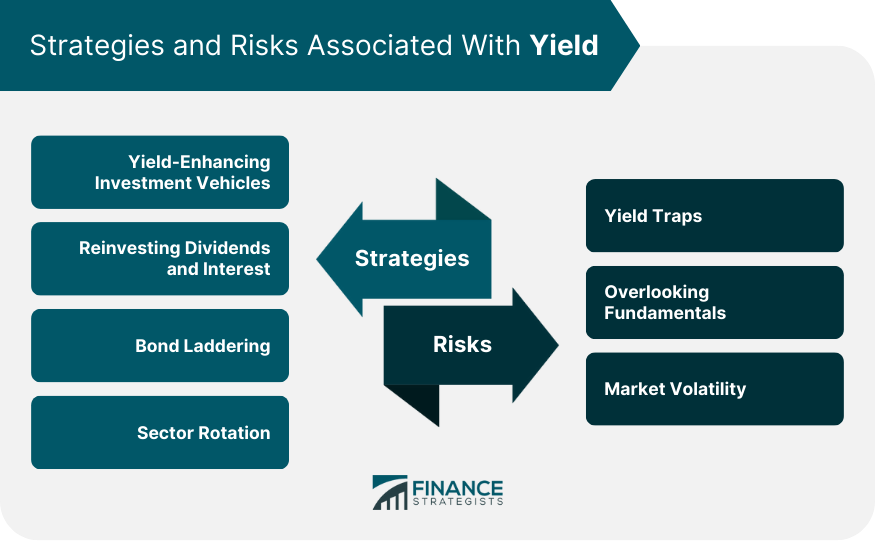

Strategies to Enhance Yield

Yield-Enhancing Investment Vehicles

Reinvesting Dividends and Interest

Bond Laddering

Sector Rotation

Risks Associated With Chasing Yield

Yield Traps

Overlooking Fundamentals

Market Volatility

Taking Caution With High Yield

Conclusion

Yield FAQs

Yield refers to the income generated by an investment over a period of time, expressed as a percentage of the invested amount, market value, or face value of the security.

A yield includes both interest earned, such as from bonds, and dividends received, such as from stocks.

Yield can be calculated by dividing Net Realized Return by Principal Amount of an investment.

While a high yield means greater returns for investors, it must be interpreted carefully.

For example, a sudden increase in the yield of stock could indicate a falling stock price. This decreases the denominator in the yield equation and so raises the resulting percentage. An increased yield can also result from an increase in dividend payments. If this does not correspond to an increase in cash flow, the issuing company may have difficulty maintaining future payments. Likewise, since bonds carry with them the risk of default, a higher than average yield could be because of a higher than average risk.

True Tamplin is a published author, public speaker, CEO of UpDigital, and founder of Finance Strategists.

True is a Certified Educator in Personal Finance (CEPF®), author of The Handy Financial Ratios Guide, a member of the Society for Advancing Business Editing and Writing, contributes to his financial education site, Finance Strategists, and has spoken to various financial communities such as the CFA Institute, as well as university students like his Alma mater, Biola University, where he received a bachelor of science in business and data analytics.

To learn more about True, visit his personal website or view his author profiles on Amazon, Nasdaq and Forbes.