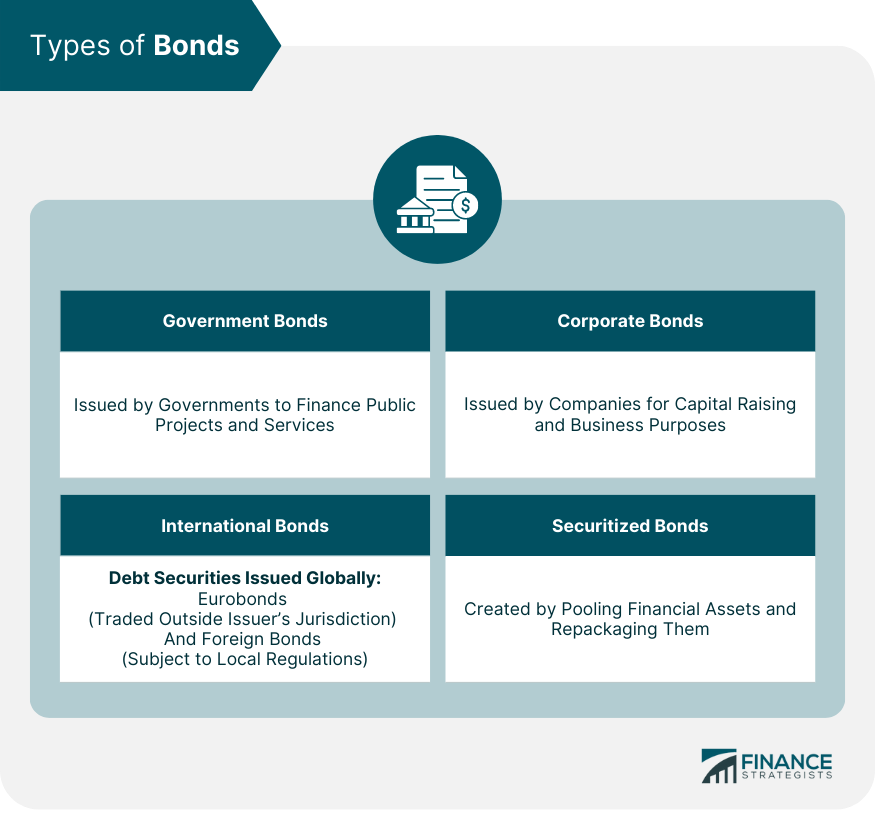

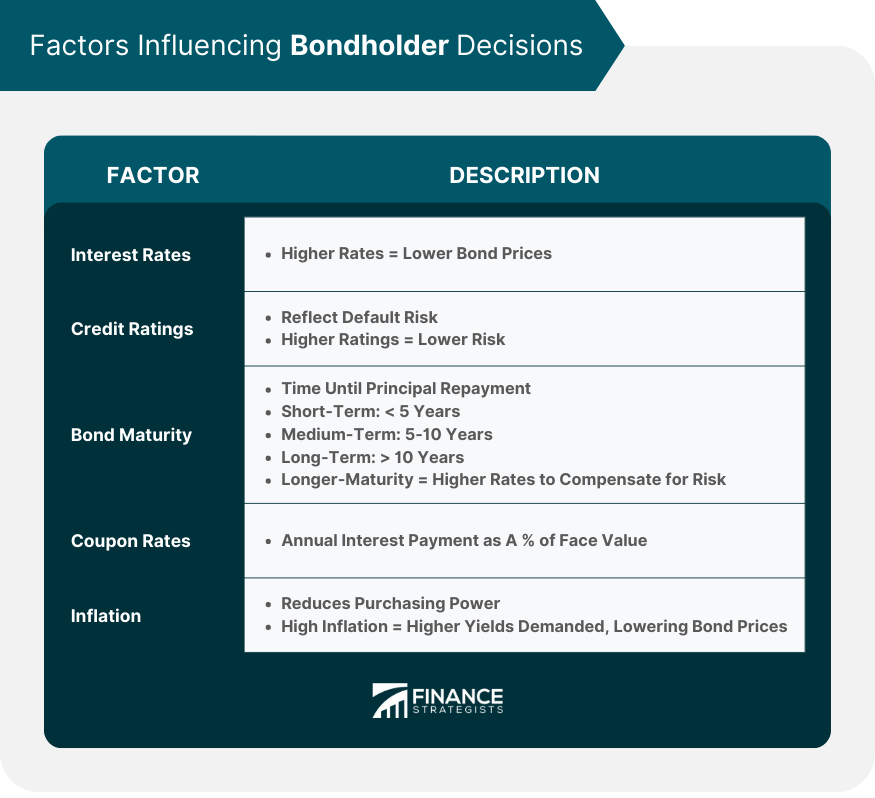

A bondholder is an individual, institution, or entity that owns a bond issued by a government, municipality, or corporation. When you purchase a bond, you effectively become a bondholder or a creditor of the entity that issued the bond. As a bondholder, you lend money to the issuer for a specified period, and in return, you receive periodic interest payments (known as coupons) and the return of the principal amount at maturity. The interest payments are typically fixed and paid at regular intervals, such as annually or semi-annually. Bondholders play a vital role in financial markets and the economy, providing capital for various projects, contributing to market stability, and offering diversification opportunities for investors. Government bonds are issued by national, state, or local governments to finance public projects and services. On the other hand, municipal bonds are issued by state and local governments to fund public infrastructure, education, or healthcare initiatives. Companies issue corporate bonds to raise capital for various business purposes, such as expansion, research, and development, or mergers and acquisitions. Investment-grade bonds are those with higher credit ratings, indicating lower default risk. In contrast, high-yield or "junk bonds" have lower credit ratings but offer higher interest rates to compensate for the increased risk. International bonds are debt securities issued by entities in the global financial markets. Eurobonds are bonds denominated in a currency different from that of the issuer's country and are typically traded outside the issuer's jurisdiction. Foreign bonds are issued by foreign entities in a domestic market, denominated in the domestic currency, and are subject to local regulations. Securitized bonds are created by pooling together various financial assets, such as mortgages or loans, and repackaging them into new securities. Mortgage-backed securities (MBS) are backed by a pool of mortgage loans, while various assets, such as auto loans or credit card receivables, back asset-backed securities (ABS). These securities allow issuers to distribute risk and provide bondholders with diversified investment options. Interest rates significantly impact bond prices, as they affect the cost of borrowing and the attractiveness of fixed-income investments. When interest rates rise, bond prices generally fall, and vice versa. Bondholders analyze the yield curve, which plots the yields of bonds with varying maturities, to gauge market expectations and make informed investment decisions. Credit ratings assess the creditworthiness of bond issuers and help bondholders evaluate the risk of default. Rating agencies, such as Standard & Poor's, Moody's, and Fitch, assign credit ratings based on factors like the issuer's financial health, debt levels, and economic outlook. Higher credit ratings indicate lower default risk, while lower ratings signal higher risk. Maturity refers to the length of time until the principal is repaid. Short-term bonds generally have less than five years, medium-term bonds range from five to ten years, and long-term bonds have more than ten years. Longer-maturity bonds tend to have higher interest rates to compensate for the increased risk of holding the investment over a longer time horizon. The coupon rate is the annual interest payment that bondholders receive, expressed as a percentage of the bond's face value. Fixed-rate bonds pay a constant coupon rate throughout the bond's life. In contrast, floating-rate bonds have coupon rates that adjust periodically based on a reference interest rate, such as the London Interbank Offered Rate (LIBOR). Zero-coupon bonds, however, do not pay regular interest but are sold at a discount and redeemed at their face value upon maturity. Inflation erodes the purchasing power of money over time, which can negatively impact bond prices and fixed-income investments. When inflation is high, investors may demand higher yields to compensate for the loss in purchasing power, pushing bond prices lower. Inflation-indexed bonds, such as Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities (TIPS), provide some protection against inflation by adjusting the principal and interest payments based on changes in the Consumer Price Index (CPI). Bondholders have the right to receive periodic interest payments and the repayment of the principal amount upon the bond's maturity. These payments' specific terms and conditions are outlined in the bond's indenture, which is the legal agreement between the issuer and bondholders. In the event of bankruptcy or liquidation, bondholders have priority over shareholders regarding claims on the issuer's assets. This means bondholders are more likely to recover a portion of their investment than shareholders, who may receive nothing. However, the recovery amount for bondholders depends on the issuer's financial situation and the seniority of the bonds in question. Bond covenants are contractual clauses that outline the obligations and restrictions placed on the issuer to protect the bondholders' interests. These covenants may include financial performance requirements, additional debt issuance restrictions, or asset sales limitations. Bondholders can enforce these covenants and may take legal action if the issuer fails to comply with their terms. Unlike shareholders, bondholders typically do not have voting rights in the issuer's corporate decisions. However, some bonds may grant bondholders specific voting rights under certain circumstances, such as approving changes to the bond's terms, the appointment of a trustee, or initiating legal proceedings against the issuer. Credit risk refers to the possibility that the bond issuer may default on its interest and principal payments. Default risk is the most direct form of credit risk and occurs when an issuer fails to meet its payment obligations. On the other hand, downgrade risk arises when a bond's credit rating is lowered, which can negatively impact its market value and make it more difficult for the issuer to refinance its debt. Interest rate risk is the potential for bond prices to decline as interest rates rise. This risk has two components: reinvestment risk, which is the possibility that bondholders may have to reinvest their interest payments at lower rates than the initial bond yield, and duration risk, which measures the sensitivity of a bond's price to changes in interest rates. Liquidity risk is the risk that bondholders may not be able to buy or sell their bonds quickly and at a fair price due to limited market demand or supply. This risk is particularly relevant for bonds with smaller issuance sizes, lower credit ratings, or those issued by less-established entities. Inflation risk is the possibility that the purchasing power of bondholders' investments will decline due to rising prices. This risk can be especially detrimental to long-term, fixed-rate bondholders, as they are locked into a fixed interest rate that may need to catch up with inflation. For investors in international bonds, exchange rate risk arises from fluctuations in the value of the foreign currency relative to their home currency. Changes in exchange rates can affect the value of the bond's principal and interest payments when converted back to the investor's domestic currency, impacting the overall return on investment. Event risk is the possibility that unforeseen events, such as natural disasters, geopolitical tensions, or regulatory changes, may negatively impact a bond's value or the issuer's ability to make interest and principal payments. These events can be difficult to predict and may significantly affect bondholders' returns. Passive bond investment strategies involve minimal active decision-making and trading. Buy-and-hold investors purchase bonds with the intention of holding them until maturity, collecting interest payments along the way. Laddering is another passive strategy, in which bondholders invest in a portfolio of bonds with staggered maturities, allowing them to reinvest principal payments at regular intervals and reduce interest rate risk. Active bond investment strategies require more hands-on decision-making and frequent trading. Interest rate anticipation involves making tactical moves based on expectations about future interest rate changes and buying or selling bonds to maximize returns. Credit analysis focuses on assessing bond issuers' financial health and creditworthiness to identify undervalued bonds or avoid potential defaults. Sector rotation involves shifting investments between different bond sectors, such as government, corporate, or international bonds, based on market conditions and economic trends. Diversification is a key component of bond investment strategies, as it helps to spread risk across a range of bond issuers, types, and maturities. By investing in a diversified portfolio, bondholders can reduce the impact of a single bond's poor performance on their overall returns. Diversification strategies may include investing in bonds from various sectors, countries, or credit ratings and allocating funds across short, medium, and long-term maturities. Bondholders are crucial participants in financial markets and the broader economy. They provide essential capital to bond issuers, help maintain market stability, and serve as a valuable diversification tool for investors. Understanding the types of bonds, including government, corporate, international, and securitized bonds, along with key factors like interest rates, credit ratings, maturity, coupon rates, and inflation, enables bondholders to make informed investment decisions. Furthermore, bondholders must be aware of their rights, their risks, and the strategies available for managing them, such as passive, active, and diversification strategies. By staying informed and engaged, bondholders can play a pivotal role in promoting the long-term health of financial markets and the global economy.What Is a Bondholder?

Types of Bonds

Government Bonds

Treasury bonds, for example, are issued by the federal government and have varying maturities, typically ranging from short-term Treasury bills to long-term Treasury bonds.Corporate Bonds

International Bonds

Securitized Bonds

Factors Influencing Bondholder Decisions

Interest Rates

Credit Ratings

Bond Maturity

Coupon Rates

Inflation

Bondholder Rights

Rights to Interest and Principal Payments

Rights During Bankruptcy

Rights in Bond Covenants

Voting Rights

Risks Faced by Bondholders

Credit Risk

Interest Rate Risk

Liquidity Risk

Inflation Risk

Exchange Rate Risk

Event Risk

Bondholder Strategies

Passive Strategies

Active Strategies

Diversification

Conclusion

Bondholder FAQs

A bondholder is an individual or entity that owns one or more bonds issued by a government, corporation, or other organization. As a bondholder, the individual or entity is entitled to receive periodic interest payments (coupon payments) and the return of the bond's principal amount upon maturity.

A bondholder has the right to receive periodic interest payments (coupon payments) based on the bond's stated interest rate and the return of the bond's principal amount upon maturity. Depending on the bond terms, bondholders may also have additional rights, such as voting rights in certain corporate actions.

A bondholder receives interest or coupon payments at regular intervals (e.g., semi-annually or annually) based on the bond's stated interest rate. These payments are typically made directly to the bondholder's designated account.

Suppose the bond issuer defaults on its debt obligations. In that case, the bondholder may not receive the scheduled interest payments and may also risk losing some or all of the principal amount invested. In such cases, bondholders may have legal recourse and may participate in debt restructuring or liquidation proceedings to recover a portion of their investment.

Yes, a bondholder can sell their bonds before the maturity date in the secondary bond market. The price at which the bond is sold may be higher or lower than the original purchase price, depending on market conditions, interest rates, and the creditworthiness of the issuer.

True Tamplin is a published author, public speaker, CEO of UpDigital, and founder of Finance Strategists.

True is a Certified Educator in Personal Finance (CEPF®), author of The Handy Financial Ratios Guide, a member of the Society for Advancing Business Editing and Writing, contributes to his financial education site, Finance Strategists, and has spoken to various financial communities such as the CFA Institute, as well as university students like his Alma mater, Biola University, where he received a bachelor of science in business and data analytics.

To learn more about True, visit his personal website or view his author profiles on Amazon, Nasdaq and Forbes.