A Z-bond, also known as an accrual bond, is a unique type of bond often found within the realm of structured finance. It is distinguished by its payment structure; it is typically the last bond to mature in a series of bonds and only receives payment after all other bond classes have been paid. The payment, which comprises the interest accrued added to the principal, is a defining feature of this investment instrument. Z-bonds came to prominence during the mortgage-backed securities boom in the 1980s. Financial institutions, looking for ways to manage risk and appeal to different types of investors, introduced these bonds as part of collateralized mortgage obligations (CMOs). Over time, Z-bonds have evolved to become a critical component of the fixed-income market, providing investors with a unique risk and reward profile. Z-bonds are characterized by their deferred interest payments. Unlike traditional bonds, which pay interest periodically over the life of the bond, Z-bonds accrue interest that is payable at maturity or when prior bond classes are paid off. This delay in interest payments leads to a phenomenon known as "compounding," where the interest, instead of being paid out, is added to the principal, and future interest accrues on this larger principal amount. In a structured finance context, Z-bonds are part of a tranche - a group of securities with similar characteristics within a larger security offering. In a typical CMO, Z-bonds are usually the last tranche, receiving payments only after other tranches have been paid off. This unique structure allows the Z-bond's principal to grow over time due to the compounding of unpaid interest. Compared to other types of bonds, Z-bonds offer higher potential returns due to their accrual structure. However, this comes with an increased level of risk. The primary differences lie in the payment structure and timing. Standard bonds pay interest at regular intervals and return the principal at maturity, while Z-bonds compound the interest until other bond classes are paid off, and only then do they start paying out. Z-bonds are typically issued as part of a CMO or other structured finance product. The issuing institution structures the offering into different tranches to appeal to different types of investors. The Z-bond tranche is designed for investors who are comfortable with a longer time horizon and potentially higher returns. Once issued, the Z-bond begins accruing interest. However, this interest is not paid out immediately. Instead, it's added to the principal, and future interest accrues on this larger amount. This process continues until the other bond classes in the tranche are paid off. At that point, the Z-bond begins paying out interest and principal to the bondholders. In a typical CMO, payments are made in a specific order. The first bond classes to receive payments are usually those with the shortest maturities, while the Z-bond, with the longest maturity, is last. This payment hierarchy allows Z-bonds to offer potentially higher returns, but it also exposes investors to more considerable risk if the underlying assets perform poorly. Z-bonds, or accretion bonds, are unique in that they do not pay out interest immediately. Instead, the interest is added to the principal of the bond and compounds over time until maturity. This means that the total return at the end of the bond's term can be significantly higher than that of a traditional bond, where interest is paid out periodically. This makes Z-bonds an attractive option for investors who are not in immediate need of cash flow and are willing to wait for potentially higher returns. Another advantage of Z-bonds is their ability to act as a hedge against falling interest rates. Since Z-bonds do not make periodic interest payments, their value is less sensitive to changes in interest rates compared to traditional bonds. When interest rates fall, the price of existing bonds typically rises. However, bonds that make regular interest payments may not see as much of a price increase because their future payments are discounted at a lower rate. Z-bonds, on the other hand, can see a greater price increase because all of their payments are at the end of the bond's term. Finally, Z-bonds can provide diversification within a fixed-income portfolio. Because they have different cash flow characteristics compared to traditional bonds, they can serve as a counterbalance in a portfolio. For instance, in a period of falling interest rates, Z-bonds may perform better than traditional bonds, helping to offset any underperformance in the rest of the portfolio. Similarly, in a period of rising interest rates, other bonds in the portfolio may help offset any underperformance by the Z-bonds. This diversification can help to reduce the overall risk of the portfolio. One of the key risks associated with Z-bonds is the delay in payments. Unlike traditional bonds, which pay interest periodically, Z-bonds do not make any payments until maturity. This means that investors must be comfortable with a longer time horizon and the potential for deferred returns. If an investor needs regular income or may need to access their investment in the short term, a Z-bond may not be the best choice. The value of a Z-bond is heavily dependent on the performance of the underlying assets. If these assets default or perform poorly, the value of the Z-bond can suffer. This is particularly relevant for Z-bonds that are part of CMOs or other asset-backed securities, where the underlying assets are loans or mortgages. If a significant number of these loans or mortgages default, the Z-bond investor could see a lower return or even a loss on their investment. While Z-bonds can serve as a hedge against falling interest rates, they can be negatively impacted by rising rates. As interest rates increase, the present value of the Z-bond's future payments decreases, which can lead to a decrease in the bond's price. Furthermore, as interest rates rise, other investments may offer higher yields, increasing the opportunity cost of holding a Z-bond. This means that investors could potentially earn more by investing in other securities, making the Z-bond less attractive. In the global bond market, Z-bonds play a unique role. They offer investors the opportunity for higher yields and serve as a useful tool for portfolio diversification. Moreover, they add liquidity to the market by offering a different kind of risk-return profile that appeals to a specific subset of investors. Market trends for Z-bonds are often tied to broader economic conditions. In periods of low-interest rates, Z-bonds can be less attractive due to their deferred interest payments. However, during times of economic uncertainty or volatility, the potentially higher returns of Z-bonds can become more appealing to investors seeking to hedge against risk. Key players in the Z-bond market are often large financial institutions that issue CMOs or other structured finance products. These can include investment banks, mortgage lenders, and government-sponsored entities like Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. On the buy side, investors range from individuals to institutional investors such as pension funds and hedge funds. Z-bonds offer unique characteristics and advantages in the financial market. They provide the potential for higher returns, act as a hedge against falling interest rates, and offer diversification within a fixed-income portfolio. However, they also come with disadvantages, such as delayed payments and dependence on the performance of underlying assets. Z-bonds play a crucial role in the global bond market by providing investors with alternative risk-return profiles and adding liquidity. Market trends for Z-bonds are influenced by economic conditions, with their appeal increasing during periods of uncertainty. Key players involved in the Z-bond market include large financial institutions as issuers and a wide range of investors on the buy side. Overall, Z-bonds offer a distinctive investment option for those seeking potentially higher returns and portfolio diversification.What Is a Z-Bond?

Understanding Z-Bonds

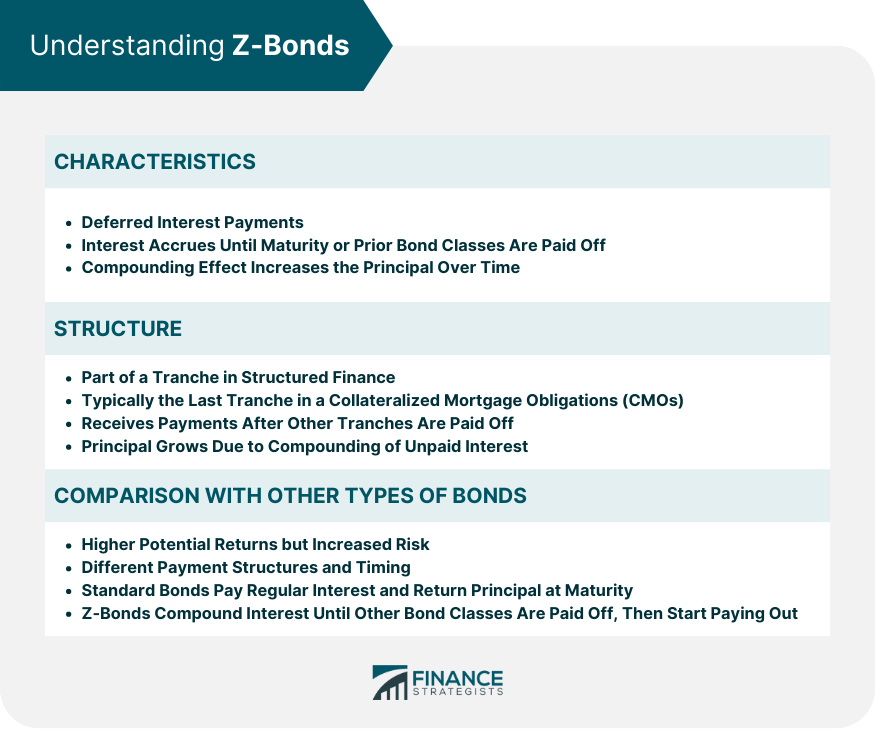

Characteristics of Z-Bonds

Structure of a Z-Bond

Comparison With Other Types of Bonds

How Z-Bonds Work

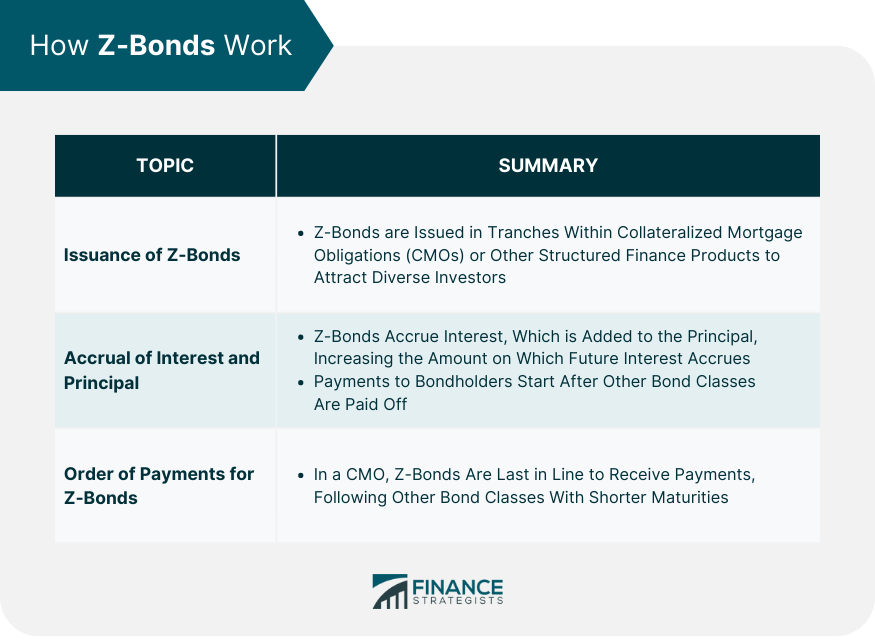

Issuance of Z-Bonds

Accrual of Interest and Principal Payment in Z-Bonds

Order of Payments for Z-Bonds Compared to Other Bond Classes

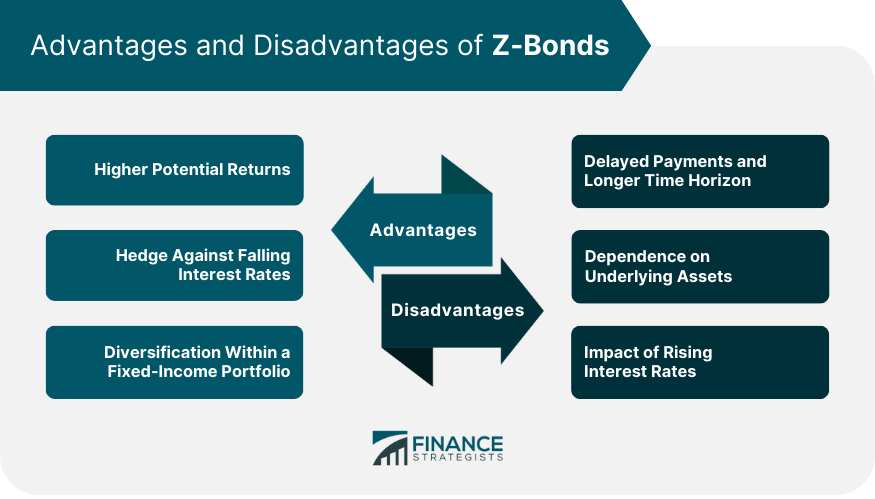

Advantages of Z-Bonds

Higher Potential Returns

Hedge Against Falling Interest Rates

Diversification Within a Fixed-Income Portfolio

Disadvantages of Z-Bonds

Delayed Payments and Longer Time Horizon

Dependence on Underlying Assets

Impact of Rising Interest Rates

Z-Bonds in the Financial Market

Role of Z-Bonds in the Global Bond Market

Market Trends for Z-Bonds

Key Players Involved With Z-Bonds

Final Thoughts

Z-Bond FAQs

A Z-Bond, also known as an accrual bond, is a type of bond that does not pay interest until the principal of all other bond classes has been paid. Instead, the interest accrues and is added to the principal, which is paid out at maturity.

A Z-Bond works by accruing interest over its lifetime, but this interest is not immediately paid out. Instead, it's added to the bond's principal. The bondholder receives payment only after all other bond classes have been paid off. This payment includes the original principal and the accrued interest.

The primary advantage of a Z-Bond is the potential for higher returns due to the compounding of interest over time. Additionally, Z-Bonds can be a good hedge against falling interest rates. However, the disadvantages include a longer investment horizon, as Z-Bonds are typically the last to be paid in a series of bonds. They can also be riskier if the underlying assets perform poorly.

Unlike most bonds that pay interest periodically, a Z-Bond's interest is added to its principal and paid out at the end of the bond's life. This creates a potential for higher returns due to compounded interest. However, this also means the bondholder must wait until all other bond classes have been paid off before receiving payment, which could increase the risk.

Z-Bonds are typically attractive to investors who can afford to wait for their returns and are seeking higher potential returns compared to traditional bonds. This can include institutional investors like pension funds and hedge funds, as well as individual investors who have a long-term investment horizon and a higher risk tolerance.

True Tamplin is a published author, public speaker, CEO of UpDigital, and founder of Finance Strategists.

True is a Certified Educator in Personal Finance (CEPF®), author of The Handy Financial Ratios Guide, a member of the Society for Advancing Business Editing and Writing, contributes to his financial education site, Finance Strategists, and has spoken to various financial communities such as the CFA Institute, as well as university students like his Alma mater, Biola University, where he received a bachelor of science in business and data analytics.

To learn more about True, visit his personal website or view his author profiles on Amazon, Nasdaq and Forbes.