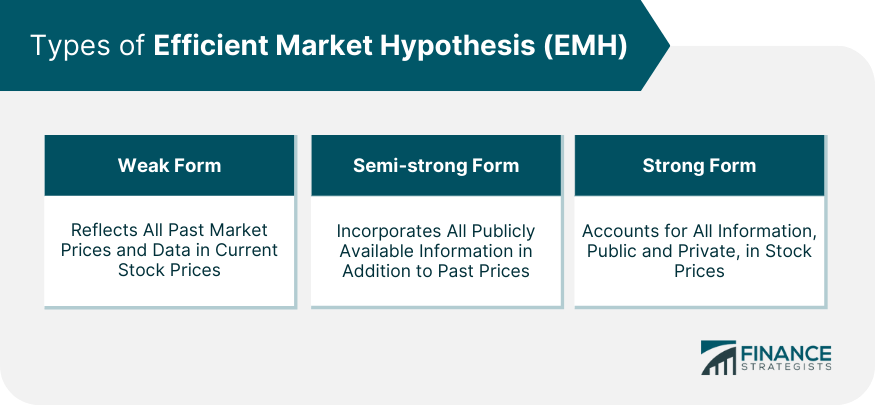

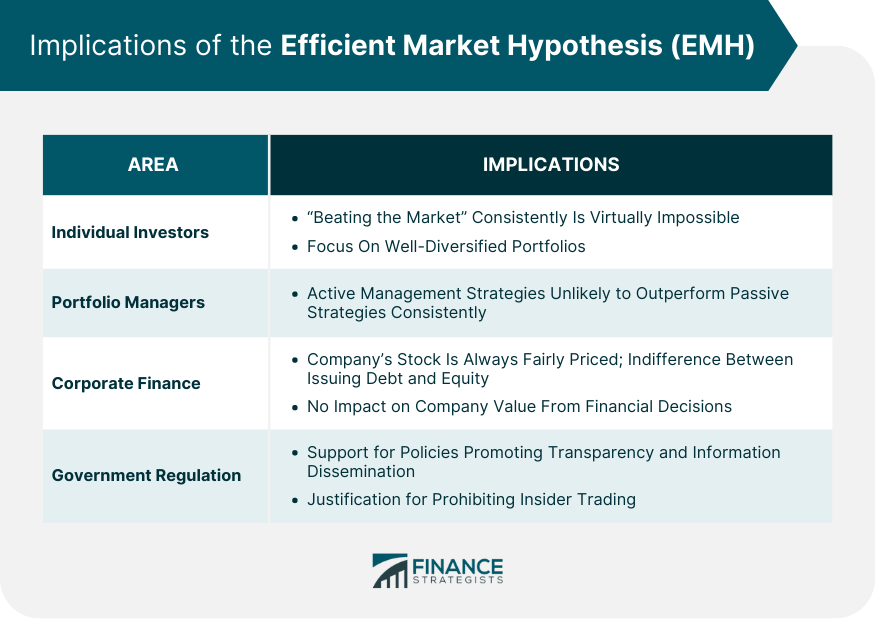

The Efficient Market Hypothesis (EMH) is a theory that suggests financial markets are efficient and incorporate all available information into asset prices. According to the EMH, it is impossible to consistently outperform the market by employing strategies such as technical analysis or fundamental analysis. The hypothesis argues that since all relevant information is already reflected in stock prices, it is not possible to gain an advantage and generate abnormal returns through stock picking or market timing. The EMH comes in three forms: weak, semi-strong, and strong, each representing different levels of market efficiency. While the EMH has faced criticisms and challenges, it remains a prominent theory in finance that has significant implications for investors and market participants. The Efficient Market Hypothesis can be categorized into the following: The weak form of EMH posits that all past market prices and data are fully reflected in current stock prices. Therefore, technical analysis methods, which rely on historical data, are deemed useless as they cannot provide investors with a competitive edge. However, this form doesn't deny the potential value of fundamental analysis. The semi-strong form of EMH extends beyond historical prices and suggests that all publicly available information is instantly priced into the market. This includes financial statements, news releases, economic indicators, and other public disclosures. Therefore, neither technical analysis nor fundamental analysis can yield superior returns consistently. The most extreme version of EMH, the strong form, asserts that all information, both public and private, is fully reflected in stock prices. Even insiders with privileged information cannot consistently achieve higher-than-average market returns. This form, however, is widely criticized as it conflicts with securities regulations that prohibit insider trading. Three fundamental assumptions underpin the Efficient Market Hypothesis. This assumption holds that the dissemination of information is perfect and instantaneous. All market participants receive all relevant news and data about a security or market simultaneously, and no investor has privileged access to information. In EMH, it is assumed that investors collectively have a rational expectation about future market movements. This means that they will act in a way that maximizes their profits based on available information, and their collective actions will cause securities' prices to adjust appropriately. In an efficient market, investors instantaneously incorporate new information into their investment decisions. This immediate response to news and data leads to swift adjustments in securities' prices, rendering it impossible to "beat the market." The EMH has several implications across different areas of finance. For individual investors, EMH suggests that "beating the market" consistently is virtually impossible. Instead, investors are advised to invest in a well-diversified portfolio that mirrors the market, such as index funds. For portfolio managers, EMH implies that active management strategies are unlikely to outperform passive strategies consistently. It discourages the pursuit of "undervalued" stocks or timing the market. In corporate finance, EMH implies that a company's stock is always fairly priced, meaning it should be indifferent between issuing debt and equity. It also suggests that stock splits, dividends, and other financial decisions have no impact on a company's value. For regulators, EMH supports policies that promote transparency and information dissemination. It also justifies the prohibition of insider trading. Despite its widespread acceptance, the EMH has attracted significant criticism and controversy. Behavioral finance argues against the notion of investor rationality assumed by EMH. It suggests that cognitive biases often lead to irrational decisions, resulting in mispriced securities. Examples include overconfidence, anchoring, loss aversion, and herd mentality, all of which can lead to market anomalies. EMH struggles to explain various market anomalies and inefficiencies. For instance, the "January effect," where stocks tend to perform better in January, contradicts the EMH. Similarly, the "momentum effect" suggests that stocks that have performed well recently tend to continue performing well, which also challenges EMH. The Global Financial Crisis of 2008 raised serious questions about market efficiency. The catastrophic market failure suggested that markets might not always price securities accurately, casting doubt on the validity of EMH. Empirical evidence on the EMH is mixed, with some studies supporting the hypothesis and others refuting it. Several studies have found that professional fund managers, on average, do not outperform the market after accounting for fees and expenses. This finding supports the semi-strong form of EMH. Similarly, numerous studies have shown that stock prices tend to follow a random walk, supporting the weak form of EMH. Conversely, other studies have documented persistent market anomalies that contradict EMH. The previously mentioned January and momentum effects are examples of such anomalies. Moreover, the occurrence of financial bubbles and crashes provides strong evidence against the strong form of EMH. Despite criticisms, the EMH continues to shape modern finance in profound ways. The EMH has been a driving force behind the rise of passive investing. If markets are efficient and all information is already priced into securities, then active management cannot consistently outperform the market. As a result, many investors have turned to passive strategies, such as index funds and ETFs. Advances in technology have significantly improved the speed and efficiency of information dissemination, arguably making markets more efficient. High-frequency trading and algorithmic trading are now commonplace, further reducing the possibility of beating the market. While the debate over market efficiency continues, the growing influence of machine learning and artificial intelligence in finance could further challenge the EMH. These technologies have the potential to identify and exploit subtle patterns and relationships that human investors might miss, potentially leading to market inefficiencies. The Efficient Market Hypothesis is a crucial financial theory positing that all available information is reflected in market prices, making it impossible to consistently outperform the market. It manifests in three forms, each with distinct implications. The weak form asserts that all historical market information is accounted for in current prices, suggesting technical analysis is futile. The semi-strong form extends this to all publicly available information, rendering both technical and fundamental analysis ineffective. The strongest form includes even insider information, making all efforts to beat the market futile. EMH's implications are profound, affecting individual investors, portfolio managers, corporate finance decisions, and government regulations. Despite criticisms and evidence of market inefficiencies, EMH remains a cornerstone of modern finance, shaping investment strategies and financial policies.Efficient Market Hypothesis (EMH) Overview

Types of Efficient Market Hypothesis

Weak Form EMH

Semi-strong Form EMH

Strong Form EMH

Assumptions of the Efficient Market Hypothesis

All Investors Have Access to All Publicly Available Information

All Investors Have a Rational Expectation

Investors React Instantly to New Information

Implications of the Efficient Market Hypothesis

Implications for Individual Investors

Implications for Portfolio Managers

Implications for Corporate Finance

Implications for Government Regulation

Criticisms and Controversies Surrounding the Efficient Market Hypothesis

Behavioral Finance and the Challenge to EMH

Market Anomalies and Inefficiencies

Financial Crises and the Question of Market Efficiency

Empirical Evidence of the Efficient Market Hypothesis

Evidence Supporting EMH

Evidence Against EMH

Efficient Market Hypothesis in Modern Finance

EMH and the Rise of Passive Investing

Impact of Technology on Market Efficiency

Future of EMH in Light of Evolving Financial Markets

Conclusion

Efficient Market Hypothesis (EMH) FAQs

The Efficient Market Hypothesis (EMH) is a theory suggesting that financial markets are perfectly efficient, meaning that all securities are fairly priced as their prices reflect all available public information. It's important because it forms the basis for many investment strategies and regulatory policies.

The three forms of the EMH are the weak form, semi-strong form, and strong form. The weak form suggests that all past market prices are reflected in current prices. The semi-strong form posits that all publicly available information is instantly priced into the market. The strong form asserts that all information, both public and private, is fully reflected in stock prices.

According to the EMH, consistently outperforming the market is virtually impossible because all available information is already factored into the prices of securities. Therefore, it suggests that individual investors and portfolio managers should focus on creating well-diversified portfolios that mirror the market rather than trying to beat the market.

Criticisms of the EMH often come from behavioral finance, which argues that cognitive biases can lead investors to make irrational decisions, resulting in mispriced securities. Additionally, the EMH has difficulty explaining certain market anomalies, such as the "January effect" or the "momentum effect." The occurrence of financial crises also raises questions about the validity of EMH.

Despite criticisms, the EMH has profoundly shaped modern finance. It has driven the rise of passive investing and influenced the development of many financial regulations. With advances in technology, the speed and efficiency of information dissemination have increased, arguably making markets more efficient. Looking forward, the growing influence of artificial intelligence and machine learning could further challenge the EMH.

True Tamplin is a published author, public speaker, CEO of UpDigital, and founder of Finance Strategists.

True is a Certified Educator in Personal Finance (CEPF®), author of The Handy Financial Ratios Guide, a member of the Society for Advancing Business Editing and Writing, contributes to his financial education site, Finance Strategists, and has spoken to various financial communities such as the CFA Institute, as well as university students like his Alma mater, Biola University, where he received a bachelor of science in business and data analytics.

To learn more about True, visit his personal website or view his author profiles on Amazon, Nasdaq and Forbes.