The weak form of market efficiency, part of the efficient market hypothesis (EMH), posits that current asset prices fully reflect all currently available security market information. This includes historical prices and rates of return. If a market is weak-form efficient, no investor can consistently achieve abnormal returns by developing trading rules based on historical price or return information. Understanding weak form efficiency is crucial in financial markets as it provides a baseline for evaluating investment strategies. If a market only achieves weak form efficiency, technical analysis strategies, which rely on past price and volume data, would not consistently yield profitable results. For these strategies to be consistently profitable, the market needs to achieve a higher level of efficiency, often referred to as semi-strong or strong form efficiency. The weak form efficiency theory, as established by economist Eugene Fama in the 1960s, is built on the premise of the random walk hypothesis. This hypothesis suggests that price changes in securities are independent and identically distributed. Thus, past prices cannot predict future prices. The theory of weak form efficiency assumes rational investors, no transaction costs, and public accessibility to all relevant information. It also assumes that investors react quickly and accurately to new information. In a weak-form efficient market, past prices have no bearing on future prices. This notion discredits technical analysis, which attempts to forecast future prices based on past trends. Trading volumes, like price information, are considered to have no predictive power in weak-form efficient markets. Volume indicators used in the technical analysis would thus need to be more effective. In weak form efficiency, dividend yields, like prices and volumes, are considered to have no impact on future returns. This contradicts certain investment strategies that favor high-dividend-yield stocks. Weak form efficiency suggests that price movements are random and not influenced by past trends. This interpretation challenges the validity of trend analysis in predicting future prices. If a market is weak form efficient, strategies based on historical data analysis, such as momentum or contrarian strategies, would not consistently outperform the market after adjusting for risk. Numerous empirical studies support weak form efficiency. For instance, the serial correlation coefficient tests on stock returns often fail to find any significant correlation, supporting the random walk hypothesis. Markets, especially large and liquid ones like the U.S. stock market, often behave consistently with weak form efficiency. Despite short-term anomalies, the market as a whole tends to reflect available information quickly. Contrary to weak form efficiency, empirical evidence such as the momentum effect and calendar effects suggest that past returns can predict future returns to some extent, at least in the short run. Behavioral finance, which considers psychological factors, argues against weak form efficiency. It suggests that cognitive biases can cause markets to deviate from efficiency. While weak form efficiency considers only past market information, semi-strong form efficiency claims that prices instantly adjust to all publicly available information, not just past prices. The strong form of efficiency goes further, arguing that prices reflect all information, public and private. This means that even insiders with private information cannot consistently earn abnormal returns. Understanding weak form efficiency can help investors make more informed decisions. For example, it suggests that strategies relying solely on past market data may not yield consistent above-average returns. This insight can help investors diversify their investment approaches and avoid over-reliance on historical data. Portfolio managers can apply the concept of weak form efficiency to manage risk and optimize returns. Recognizing that past market data is not predictive of future returns, portfolio managers can adopt strategies that are less dependent on historical trends and more focused on other factors, such as fundamental analysis. Despite the principle of weak form efficiency, market anomalies occur. These anomalies, such as the January effect, where stocks have historically performed better in January, contradict the notion that past price data cannot predict future returns. While weak form efficiency assumes that all investors have access to and process all available information, information processing capabilities vary among investors. Some investors may be better equipped to understand and react to new information, potentially leading to market inefficiencies. A weak form of efficiency is a form of market efficiency that believes that all past prices of a stock are reflected in its current price. Therefore, it is impossible to achieve above-average returns based on trading systems that rely solely on historical price or return data. Despite its limitations and the existence of market anomalies, weak form efficiency plays a crucial role in understanding how financial markets work. It forms the baseline for evaluating investment strategies and provides a lens through which to view price movements and the impact of past market data. As markets continue to evolve with technological advancements and information dissemination, the relevance of weak form efficiency is likely to be further scrutinized. New developments, such as algorithmic trading and artificial intelligence, could challenge or reinforce the principles of weak form efficiency. To navigate the complexities of market efficiencies, having a sound wealth management strategy is crucial to navigate the complexities of market efficiencies. Whether you're a beginner or an experienced investor, professional guidance can help you understand and apply these theories in your investment journey. Reach out to a trusted financial advisor to discuss your portfolio strategy today.What Is Weak Form Efficiency?

Theory of Weak Form Efficiency

Foundation of the Theory

Assumptions Underlying the Theory

Components of Weak Form Efficiency

Past Price Information

Trading Volume

Dividend Yield

Implications of Weak Form Efficiency

Interpretation of Price Movements

Impact on Investment Strategies

Evidence Supporting Weak Form Efficiency

Empirical Studies

Positive Observations

Criticisms Against Weak Form Efficiency

Contradictory Empirical Evidence

Behavioral Finance Perspectives

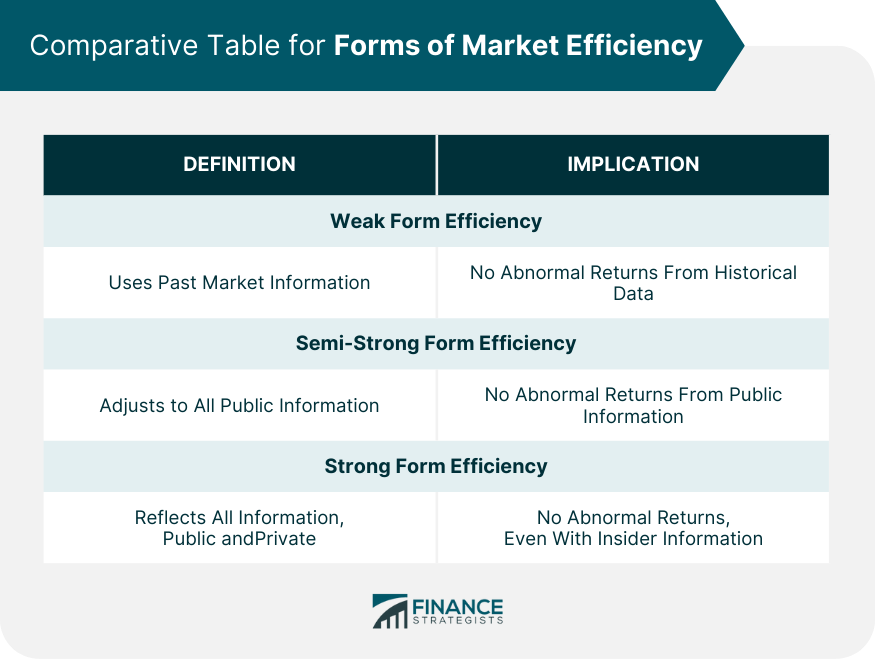

Weak Form Efficiency vs Other Forms of Market Efficiency

Semi-strong Form Efficiency

Strong Form Efficiency

Practical Applications of Weak Form Efficiency

In Investment Decisions

In Portfolio Management

Limitations and Challenges in Weak Form Efficiency

Market Anomalies

Limitations of Information Processing

Final Thoughts

Weak Form Efficiency FAQs

Weak form efficiency states that current stock prices reflect all the past market information, meaning that only investors can consistently outperform the market using strategies based on past price or return data.

If a market is weak-form efficient, strategies that rely on technical analysis or historical price data would not be consistently profitable, as all past information is already reflected in current prices.

Other than weak form efficiency, there are semi-strong form and strong form efficiencies. Semi-strong form efficiency asserts that all public information is reflected in stock prices, while strong form efficiency argues that all public and private information is reflected in stock prices.

Yes, market anomalies, which are patterns of returns that seem to contradict the efficient market hypothesis, can occur even in a weak-form efficient market. Examples include the January effect and the momentum effect.

Behavioral finance argues that cognitive biases and errors can lead investors to behave irrationally, causing markets to deviate from efficiency. This contradicts the weak form efficiency assumption of rational investors who always optimize their portfolios based on available information.

True Tamplin is a published author, public speaker, CEO of UpDigital, and founder of Finance Strategists.

True is a Certified Educator in Personal Finance (CEPF®), author of The Handy Financial Ratios Guide, a member of the Society for Advancing Business Editing and Writing, contributes to his financial education site, Finance Strategists, and has spoken to various financial communities such as the CFA Institute, as well as university students like his Alma mater, Biola University, where he received a bachelor of science in business and data analytics.

To learn more about True, visit his personal website or view his author profiles on Amazon, Nasdaq and Forbes.