A Special Purpose Acquisition Company (SPAC) is a "blank check" shell firm created solely to raise funds via an initial public offering (IPO) to acquire a private company, making it public. SPACs offer private companies an alternative, expedited route to public markets, bypassing the traditional, time-consuming IPO process. Despite being around for years, SPACs have recently soared in popularity, especially during the uncertain times of 2020, due to their relative simplicity and speed. They've gained significant traction, making up a large part of the IPO market, with many high-profile business leaders and investors sponsoring them. Understanding the workings of SPACs can provide new opportunities for growth and potentially high returns, making them a noteworthy consideration in the current financial landscape. The structure of a SPAC involves several vital entities, including sponsors, public shareholders, and the eventual target company. The sponsors are typically individuals or firms with expertise in a specific sector or business strategy. They form the SPAC and provide the initial capital, commonly known as the "risk capital." The sponsors are usually rewarded with founder shares, which may equate to about 20% of the final public company's equity. Public shareholders purchase units in the SPAC during the IPO. Each unit usually consists of one common share and a fraction of a warrant, which provides the right to purchase more shares in the future at a set price. These public shareholders become the equity holders in the final public company if a successful merger or acquisition is achieved. The target company is the business the SPAC aims to acquire or merge with. The identity of this company is usually not known at the time of the SPAC's IPO. The target is typically a private company that becomes public due to the SPAC transaction, avoiding the traditional IPO process. Launching a SPAC IPO involves filing a prospectus with the SEC detailing the SPAC's management team, strategy, and target sectors. Once approved, the SPAC's shares are listed on a stock exchange, and institutional and retail investors can purchase them. Underwriters, typically investment banks, assist in the IPO process by helping price the offering, sell securities, and guarantee a certain amount raised. They act as intermediaries between the SPAC and potential investors. Pricing a SPAC's securities is more straightforward than a traditional IPO, as there's no underlying business to value. Units are typically offered at a standard price of $10 each, comprising one share and a fraction of a warrant. SPACs are designed to acquire or merge with existing companies, making them an alternative to traditional IPOs for companies seeking to go public. SPACs are created by sponsors—usually a group of experienced industry or private equity investors. After the SPAC IPO, the funds are placed into an interest-bearing trust account. The sponsors have a set timeframe, typically 18 to 24 months, to identify and complete a merger with a target company. The acquisition or merger process, often called the De-SPAC process, is a critical phase in a SPAC's lifecycle. It involves identifying a suitable target company, conducting due diligence, negotiating transaction terms, and merging with or acquiring the target company. The De-SPAC process concludes with the SPAC taking the target company public, effectively bypassing the traditional initial public offering (IPO) process. This path to going public has gained popularity as it can be quicker, less costly, and involves less regulatory scrutiny than a traditional IPO. The acquisition process is a crucial part of the SPAC model. Once a SPAC has been formed and raised capital through an IPO, it begins the search for an acquisition target. The first step in the SPAC acquisition process is identifying a target company. The sponsors use their expertise and industry connections to find a private company interested in going public through a merger with the SPAC. The target company is typically in the same industry as the SPAC sponsors' area of expertise. The identification process can be extensive and rigorous, as the target company will ultimately determine the future of the SPAC. After identifying a target company, the SPAC, and the target company negotiate. This step culminates in the acquisition agreement, which details the terms and conditions of the proposed merger. The tours usually include the merger's price, the management structure post-merger, and the way forward for the combined entity. Due diligence is performed during this phase to verify the target company's financial and operational status. Once the acquisition agreement is finalized, it must be approved by the SPAC shareholders. The merger process is completed if approved, and the SPAC takes the target company public. The SPAC's shareholders vote on the proposed acquisition. If a majority of shareholders approve, the acquisition proceeds. If the SPAC shareholders reject the proposed acquisition, the SPAC is liquidated, and the funds are returned to the shareholders. Upon completion of the merger, the SPAC's ticker symbol is usually replaced with a new one representing the acquired company. After the merger, the new public company begins its operations, guided by the plans laid out in the acquisition agreement. The newly formed company focuses on executing its business strategies and growing its operations. The acquired company can leverage the capital raised through the SPAC IPO to fund its growth and expansion plans. The management team, usually a combination of the original SPAC's sponsors and the acquired company's leaders, works to increase shareholder value. As a public company, the newly merged entity must comply with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) reporting requirements. This includes regular financial reporting, maintaining appropriate internal controls, and adhering to public company governance standards. Failure to comply with these requirements can result in penalties and damage the company's reputation. Investor participation in a SPAC can take several forms. They can purchase units during the IPO, shares or warrants on the open market post-IPO, or participate in the PIPE (Private Investment in Public Equity) transaction that often accompanies the merger announcement. Investing in SPACs offers the potential for high returns but also carries significant risk. SPACs need a business history as blank check companies, making them challenging to evaluate. They can offer sizable gains if the merger is successful and the acquired company performs well. If a suitable acquisition isn't made within the set timeline (usually 18-24 months), the SPAC is liquidated, and IPO investors are returned their initial investment. For investors, due diligence in SPACs primarily revolves around assessing the track record and credibility of the sponsors, as well as the potential growth of the target sector. This process may involve analyzing the sponsors' past performances, expertise, and their acquisition strategy's viability. Special Purpose Acquisition Companies (SPACs) have emerged as a popular alternative route for companies looking to go public. They offer several advantages in the Mergers and Acquisitions (M&A) space. SPAC mergers can be executed more rapidly than traditional initial public offerings (IPOs). A traditional IPO process involves a company preparing extensive documentation, conducting a roadshow to attract investors, and waiting for regulatory approvals. A SPAC merger can bypass many of these steps, allowing a company to go public in months rather than a year or more timeline. With a SPAC, the target company can negotiate deal terms directly with the SPAC's sponsors rather than dealing with a broad market of investors. This can provide more financial flexibility and control over the terms of the deal. SPACs are often sponsored by teams with substantial industry experience or private equity firms. This can provide target companies with strategic guidance and support that could be helpful in their growth journey. Despite the many advantages, SPACs also have several disadvantages that must be considered. In a SPAC merger, there can be significant dilution due to the founder shares owned by the SPAC sponsors. These founder shares typically represent 20% of the equity, which can dilute the stake of other shareholders post-merger. Although SPACs have a timeline within which they must complete a merger (usually 18-24 months), there's no guarantee they'll find a suitable target within this period. If a suitable candidate isn't identified and the merger doesn't occur, the SPAC is liquidated, and the money is returned to the investors, potentially leading to lost time and opportunity costs. While SPACs face less regulatory scrutiny during the IPO process, they may face more scrutiny during the de-SPAC process. Concerns about the transparency of SPAC transactions and the quality of companies being taken public through this method may increase the risk of future regulatory scrutiny. The success of a SPAC is highly dependent on the abilities and reputation of its sponsors. A less experienced or less reputable sponsor may need help identifying a suitable target or negotiating favorable deal terms. This dependence on the sponsor introduces additional risk to the SPAC transaction. The SEC reviews the SPAC's prospectus during the IPO process. It monitors the activities of the SPAC to ensure it adheres to securities laws and acts in the best interests of shareholders. SPACs face several regulatory challenges. For instance, the due diligence process for a SPAC is usually conducted privately, which can lead to a lack of transparency. Moreover, potential conflicts of interest can arise due to the structure of SPACs, which often favor sponsors over ordinary shareholders. Given the recent surge in SPAC popularity, the SEC has indicated plans to increase its scrutiny of these entities. This heightened attention may lead to new regulations to enhance transparency, protect investors, and ensure market integrity. SPACs represent an innovative and increasingly popular means of taking companies public. They offer numerous benefits, including speed, simplicity, and the potential for significant returns. However, they also carry substantial risks, from regulatory uncertainty to potential conflicts of interest. For investors, SPACs offer a new asset class with unique risk-return characteristics. For private companies, SPACs provide an alternative route to public markets that can bypass some of the complexities of a traditional IPO. While SPACs offer exciting opportunities, they also involve significant risks. It's essential to perform diligent research or seek advice from wealth management professionals before investing.What Is a Special Purpose Acquisition Company (SPAC)?

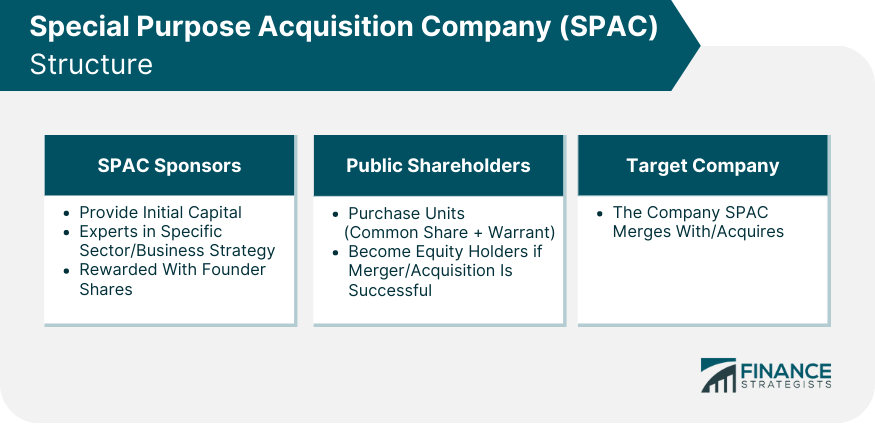

Special Purpose Acquisition Company (SPAC) Structure

SPAC Sponsors

Public Shareholders

Target Company

SPAC Initial Public Offering (IPO)

Process of Launching an IPO

Role of Underwriters

Pricing Considerations

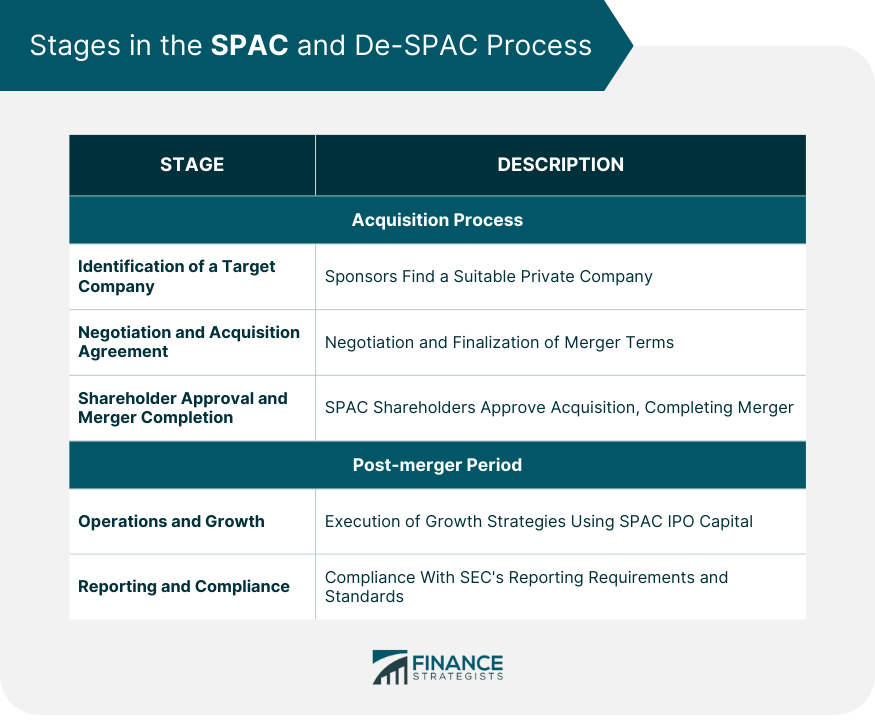

SPAC and De-SPAC Process

Acquisition Process

Identification of a Target Company

Negotiation and Acquisition Agreement

Shareholder Approval and Merger Completion

Post-merger Period

Operations and Growth

Reporting and Compliance

SPAC Investment Considerations

Investor Participation

Risks and Opportunities

Due Diligence Process

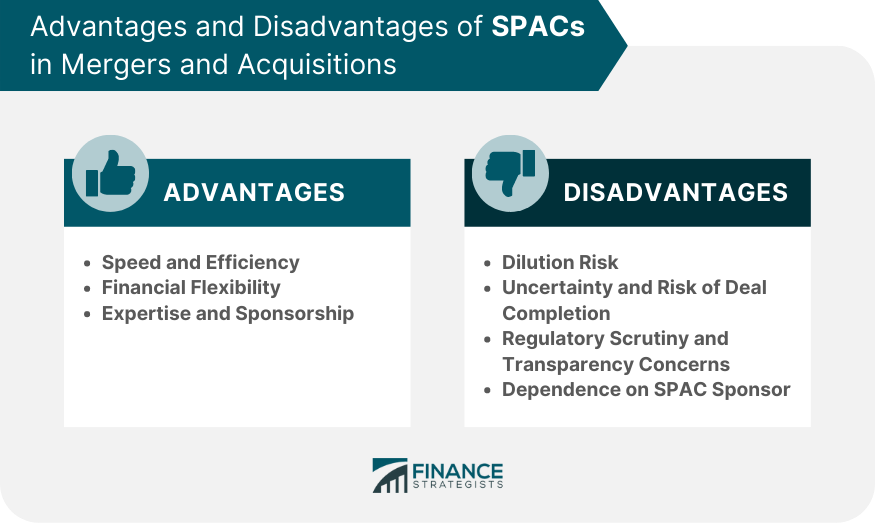

Advantages and Disadvantages of SPAC in Mergers and Acquisitions

Advantages

Speed and Efficiency

Financial Flexibility

Expertise and Sponsorship

Disadvantages

Dilution Risk

Uncertainty and Risk of Deal Completion

Regulatory Scrutiny and Transparency Concerns

Dependence on SPAC Sponsor

Regulatory Environment for SPACs

Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) Oversight

Regulatory Challenges

Recent Regulatory Changes

Conclusion

Special Purpose Acquisition Company (SPAC) FAQs

A Special Purpose Acquisition Company (SPAC) is a "blank check" shell corporation designed to take companies public without going through the traditional IPO process. SPACs are created by investors or sponsors, to merge with a private company. Once the merger is complete, the private company becomes publicly traded.

A group of sponsors with expertise in a particular industry or business sector creates a SPAC. The SPAC then raises capital through an IPO, placing the funds into a trust. The funds are used to acquire a private company, effectively publicizing that company. The shareholders of the SPAC and the target company agree to the terms of the merger, and the target company's shares become public and trade on an exchange.

Investing in a SPAC can offer significant rewards but also carries substantial risks. On the reward side, SPACs can offer retail investors a way to get in on the ground floor of a potentially promising company. However, SPACs also carry risks. Because they do not have an underlying business, SPACs can take time to evaluate. Also, if a SPAC does not complete an acquisition within the stipulated period (typically 18-24 months), it will be liquidated, and investors will get their money back, potentially without any profit.

A SPAC differs from a traditional IPO in several ways. In a traditional IPO, a company goes through a rigorous process, including audits, filings, and a roadshow to attract investors. Conversely, a SPAC allows a company to bypass these steps and go public by merging with the SPAC. This process can be quicker and less costly than a traditional IPO.

Given the rapid rise of SPACs in recent years, they will likely remain a fixture in the financial market for the foreseeable future. However, the landscape could change depending on regulatory changes and market conditions. As with any investment, potential SPAC investors should carefully consider their risk tolerance and objectives.

True Tamplin is a published author, public speaker, CEO of UpDigital, and founder of Finance Strategists.

True is a Certified Educator in Personal Finance (CEPF®), author of The Handy Financial Ratios Guide, a member of the Society for Advancing Business Editing and Writing, contributes to his financial education site, Finance Strategists, and has spoken to various financial communities such as the CFA Institute, as well as university students like his Alma mater, Biola University, where he received a bachelor of science in business and data analytics.

To learn more about True, visit his personal website or view his author profiles on Amazon, Nasdaq and Forbes.