A Dutch Auction, also known as descending price auction, is a type of auction in which the auctioneer begins with a high asking price and lowers it until a participant is willing to accept the auctioneer's price, or a predetermined reserve price is reached. The winning participant pays the last announced price. This type of auction is in stark contrast to traditional English auctions, which start with a low price and increase with each subsequent bid. Dutch Auctions are named after their origin in the Dutch flower markets, where they were commonly used to sell large quantities of goods quickly and efficiently. They were primarily used in the flower markets for selling large quantities of tulips and other flowers. The Dutch Auction gained its reputation for efficiency in these markets, as it allowed for rapid price discovery and high volumes of trade. The Dutch Auction process begins when the auctioneer announces a high starting price. The price is then gradually lowered until a bidder agrees to pay the current price. The rate at which the price is lowered, and the intervals between price drops, depend on the auctioneer's discretion and the nature of the auction. The first bidder to accept the current price wins the auction and pays the price at which they entered the bid. In auctions involving multiple identical items, the process continues until all items are sold or the reserve price is reached. In a Dutch Auction, participants are typically buyers who place bids for the goods or assets on sale. They need to carefully evaluate the value of the items in order to determine the price they are willing to pay. The auctioneer, who may be the seller or an appointed individual, manages the auction, sets the initial price, and reduces it until a sale is made. The roles and strategies of participants in a Dutch Auction can vary depending on the specifics of the auction and the nature of the items for sale. Dutch Auctions are commonly used for selling a wide variety of assets and commodities. These include perishable goods such as flowers and agricultural products, which need to be sold quickly to prevent their value from depreciating. In financial markets, Dutch Auctions are used to issue securities like bonds and shares. The U.S. Treasury, for example, uses this type of auction to sell Treasury bills, notes, and bonds. Corporations also use Dutch Auctions for share buyback programs. In a Dutch Auction, the auctioneer plays a crucial role in managing the auction process. They start the auction by setting a high initial price, then gradually lower it until a bidder accepts the price. The auctioneer must carefully determine the pace of the price drop to balance between selling the item quickly and achieving the highest possible price. The auctioneer also has the responsibility of ensuring that the auction rules are clear to all participants and that the auction is conducted in a fair and transparent manner. This involves maintaining open communication with bidders and effectively managing the bidding process. Bidders watch as the auctioneer steadily lowers the price, and when a bidder agrees to the current price, they signal their acceptance, usually by raising a hand or otherwise signaling the auctioneer. In a Dutch Auction involving multiple items, the bidders who agree to pay the highest prices are awarded the items first. The auction continues until all items are sold or the reserve price is reached. Each winning bidder pays the price at which they entered the bid, not the final price. The clearing price in a Dutch Auction is the price at which the supply of the items for sale matches the demand from the bidders. In other words, it is the price at which all items can be sold without any remaining. For auctions involving multiple identical items, the clearing price is the price of the final successful bid, at which point all the items have been sold. All winning bidders pay this clearing price for their items, regardless of the prices at which they initially bid. The allocation of assets in a Dutch Auction depends on the nature of the items for sale and the rules of the auction. If the auction involves a single item, the asset is awarded to the first bidder who accepts the auctioneer's price. In auctions with multiple identical items, assets are usually allocated based on the prices the bidders agreed to pay. The highest bidders are awarded the items first, and this continues until all items are allocated or the reserve price is reached. By starting from a high price and lowering it incrementally, Dutch Auctions allow the market to quickly determine the price at which supply and demand balance. This feature makes Dutch Auctions particularly useful for new products or assets where the market price is not yet established, as well as for selling large quantities of goods or assets quickly. The auction process is quick, as the first bidder to accept the current price wins. This makes Dutch Auctions ideal for perishable goods and any situation where time is a factor. Furthermore, in situations with multiple identical items, Dutch Auctions allow for simultaneous bidding and allocation of all items, which can be much quicker and more efficient than selling each item individually. Dutch Auctions are transparent because all bidders participate in the same process and each has an equal opportunity to win based on their individual valuation of the item. This can increase confidence in the fairness of the auction and make participants more likely to engage in the process. The transparency of Dutch Auctions extends to the pricing process. Each price reduction is done openly, and the final sale price is visible to all participants. The auctioneer has the discretion to set the pace of the price drop, depending on the nature of the item for sale and market conditions. This flexibility can allow the auctioneer to adapt the auction to achieve the best possible outcome. In addition, Dutch Auctions can accommodate a wide variety of items, from single unique items to large quantities of identical goods. This makes Dutch Auctions applicable in many different contexts and markets. If bidders agree amongst themselves to wait until the price drops to a certain level before bidding, they can artificially lower the final sale price. However, effective auction management and rules can help mitigate this risk. For example, the auctioneer can set a reserve price, which is the minimum price at which the item can be sold. Dutch Auctions may suffer from a lack of participation if potential bidders believe they have little chance of winning or if they are uncomfortable with the auction format. If few bidders participate, the final sale price may be lower than it could have been with more competition. The lack of participation could also stem from the fear of the "winner's curse," where the winning bidder realizes they have overpaid for the item after the auction. This fear can be particularly strong in Dutch Auctions, where the winner is the first to bid. An unscrupulous participant with deep pockets could theoretically drive down the price by quickly accepting low prices, deterring other bidders, and then reselling the items at a higher price. To prevent such manipulation, some Dutch Auctions employ rules such as "hard closes" at certain price levels or require bidders to prequalify before the auction. Dutch Auctions are often used in the initial public offerings (IPOs) of companies. In this context, a Dutch Auction can help ensure that the shares are sold at the highest price the market is willing to pay. Google's IPO in 2004 is a well-known example of a Dutch Auction IPO. The Dutch Auction format allows all interested investors, not just institutional investors, to participate in the IPO. This can help democratize the IPO process and potentially lead to a more equitable distribution of shares. Many governments, including the U.S. Treasury, use Dutch Auctions to sell securities such as Treasury bonds, notes, and bills. The aim is to raise capital quickly and efficiently, and to ensure the securities are sold at a fair market price. In these auctions, the Treasury sets a high starting price and then lowers it until all securities are purchased. Winning bidders pay the price at which they bid, which ensures the government raises the maximum amount of capital possible. Corporations often use Dutch Auctions to repurchase their own shares from the market, a process known as a share buyback. In a Dutch Auction share buyback, the company offers to buy back shares within a certain price range. Shareholders then submit the number of shares they want to sell and the price within that range they are willing to accept. The company then purchases the shares starting from the lowest price until they reach the number of shares they aimed to repurchase. A Dutch Auction is a unique type of auction where the auctioneer starts with a high asking price and then lowers it until a participant is willing to accept that price. This method of auction is well-suited for price discovery, efficient in nature, transparent, and flexible. This format involves a bidding process where participants indicate the quantity they desire and the price they are willing to pay. The auctioneer determines the clearing price, which is the lowest price at which all available assets can be sold. Dutch Auctions offer several advantages, including efficient price discovery, transparency, and flexibility. They are commonly used in Initial Public Offerings (IPOs), government securities auctions, and corporate buybacks. However, Dutch Auctions also have limitations, such as the potential for collusion, low participation, and the risk of market manipulation. Understanding the mechanics of a Dutch Auction, its advantages, and limitations allows potential participants to make informed decisions when engaging in such auctions.What is a Dutch Auction?

Dutch Auction Process

Overview

Participants in Dutch Auctions

Types of Assets Commonly Auctioned

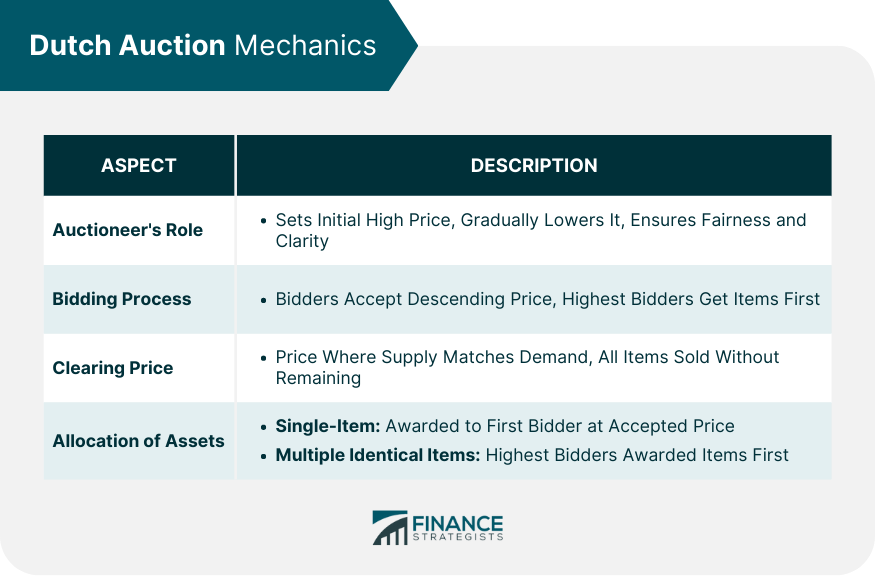

Mechanics of a Dutch Auction

Auctioneer's Role

Bidding Process

Determining the Clearing Price

Allocation of Assets

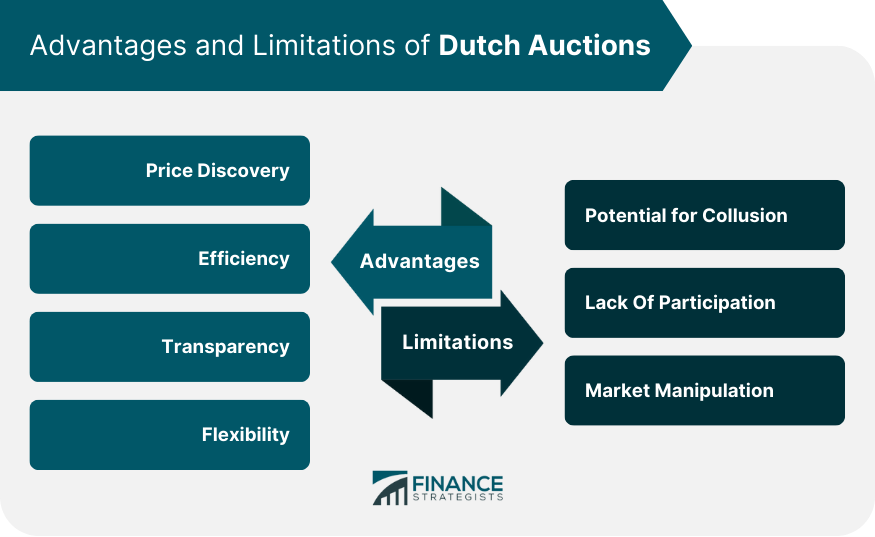

Advantages of Dutch Auctions

Price Discovery

Efficiency

Transparency

Flexibility

Limitations of Dutch Auctions

Potential for Collusion

Lack of Participation

Market Manipulation

Applications of Dutch Auctions

Initial Public Offerings (IPOs)

Government Securities Auctions

Corporate Buybacks

Conclusion

Dutch Auction FAQs

A Dutch Auction, also known as a descending price auction, is a type of auction where the auctioneer starts with a high asking price and then lowers it until a participant agrees to that price.

Bidders watch as the auctioneer steadily lowers the price. When a bidder agrees to the current price, they signal their acceptance to the auctioneer. The first bidder to do so wins the auction.

Dutch Auctions are known for their rapid price discovery, efficiency, transparency, and flexibility. They are used in a variety of settings to sell a wide range of items.

Some limitations of Dutch Auctions include the potential for collusion among bidders, lack of participation, and market manipulation.

Dutch Auctions are used in various sectors including initial public offerings (IPOs) of companies, government securities auctions, and corporate share buybacks.

True Tamplin is a published author, public speaker, CEO of UpDigital, and founder of Finance Strategists.

True is a Certified Educator in Personal Finance (CEPF®), author of The Handy Financial Ratios Guide, a member of the Society for Advancing Business Editing and Writing, contributes to his financial education site, Finance Strategists, and has spoken to various financial communities such as the CFA Institute, as well as university students like his Alma mater, Biola University, where he received a bachelor of science in business and data analytics.

To learn more about True, visit his personal website or view his author profiles on Amazon, Nasdaq and Forbes.