The January Effect is a phenomenon in financial markets where securities, especially those of small-cap companies, experience higher returns in the month of January compared to other months of the year. The purpose of identifying this effect is to help investors potentially capitalize on these increased returns. Several theories have been proposed to explain this anomaly, including tax-loss selling in December, window-dressing by fund managers, and an increase in investment due to year-end bonuses. Some also attribute it to psychological factors such as increased investor optimism at the beginning of a new year. Despite these theories, the January Effect is not consistent and comes with its own set of risks, and it should be considered as part of a comprehensive investment strategy rather than a standalone approach. One of the most widely accepted explanations for the January Effect lies in the tax-loss selling theory. In the United States and several other countries, the tax year ends in December. Many investors sell stocks that have declined throughout the year in December to establish a capital loss, which can then be used to offset capital gains elsewhere in their portfolio. As a result, these stocks' prices are pushed down artificially. When January arrives, investors are free to reinvest, often buying back the same stocks they sold in December, thus driving up prices. Another theory explaining the January Effect is window dressing. Fund managers, especially those of mutual funds and hedge funds, are known to sell off underperforming stocks at year-end to improve their year-end portfolio appearance – a practice known as 'window-dressing.' Subsequently, in January, these managers have fresh capital to invest, leading to a surge in buying activity that can drive up prices. Another potential explanation for the January Effect is related to the release of information. Companies often release annual results and forecasts in January, which can lead to increased buying if the news is positive. The increased activity and enthusiasm can lead to higher returns during this period. Psychological theories also offer a perspective on the January Effect. The optimism associated with the start of a new year may drive investors to invest more aggressively in January, pushing up stock prices. Furthermore, bonuses paid at year-end can increase the amount of investment capital available in January, contributing to increased demand for stocks. Various studies have provided empirical evidence supporting the January Effect. For instance, a 1976 study by Rozeff and Kinney noted that from 1904 to 1974, the average return during the month of January was significantly higher than in any other month. Evidence of the January Effect is not confined to the United States. Research shows the effect is evident in many developed and emerging markets. However, the strength and presence of the effect may vary depending on the unique characteristics of each market, such as the timing of tax years and different market structures. The January Effect is not uniform across all sectors. Some sectors, such as technology and finance, have shown more pronounced January Effects than others. These sector-specific observations suggest that there may be factors unique to certain industries that exacerbate or diminish the January Effect. For investors, understanding the January Effect can provide an edge. By expecting increased returns in January, investors can time their investments to benefit from this anomaly. However, it's important to note that, like any market anomaly, the January Effect doesn't guarantee returns and comes with its own set of risks. The January Effect also plays a role in risk management. An investor who is heavily invested in a particular stock might choose to sell in December to realize a loss for tax purposes and then repurchase the stock in January. This could lead to a short-term increase in the risk profile of the investor's portfolio. The January Effect has implications for asset allocation. For instance, some investors might overweight equities in January and then adjust their portfolios throughout the rest of the year. However, it's essential to consider other factors, such as the investor's risk tolerance, financial goals, and market conditions. The Efficient Market Hypothesis (EMH) posits that it is impossible to beat the market because stock market efficiency causes existing share prices to always incorporate and reflect all relevant information. The existence of the January Effect contradicts the EMH, leading to discussions around the completeness and applicability of the EMH. Some critics argue that the January Effect is driven by outliers, particularly small, speculative companies that can have large price swings. When these outliers are removed, they argue, the January Effect disappears. Recent studies have also called the January Effect into question. Some have suggested that the January Effect has lessened in recent years, potentially due to increased awareness and attempts by investors to capitalize on it. Changes in tax laws can have a significant impact on the January Effect. For example, if the tax year was changed to end in a month other than December, the selling pressure associated with tax-loss selling might shift to a different month, potentially diminishing or eliminating the January Effect. With the globalization of financial markets, investors have more choices than ever before. This globalization could potentially dilute the January Effect as investment flows become more evenly distributed throughout the year. The advent of robo-advisors and algorithmic trading has changed the investment landscape. These technologies have the potential to diminish or amplify the January Effect, depending on how they're programmed. For example, if robo-advisors are programmed to rebalance portfolios at the end of the year, this could amplify selling pressure in December and buying pressure in January, strengthening the January Effect. The January Effect is a widely observed financial phenomenon where securities, particularly small-cap companies, witness higher returns in January compared to other months. It's potentially explained by tax-loss selling, window-dressing by fund managers, the release of positive company forecasts, and increased investor optimism. Despite evidence supporting this effect, its reliability as an investment strategy is controversial due to its inconsistency and risk factors. It stands in contradiction to the Efficient Market Hypothesis, and its prominence may be waning due to changes in tax laws, globalization, and the rise of technology in finance. As such, while the January Effect is intriguing, it should not be used as a standalone investment strategy but rather considered as part of a comprehensive, risk-managed approach to portfolio allocation.January Effect Overview

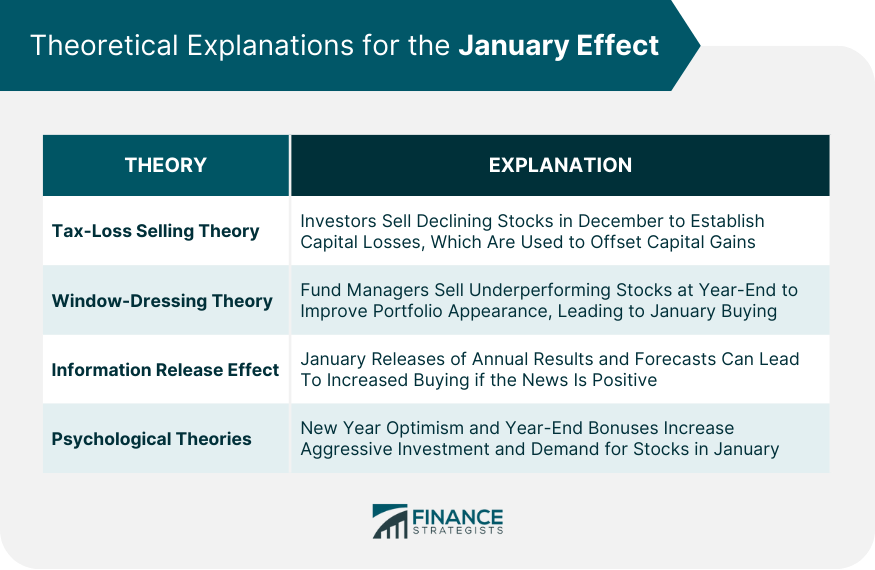

Theoretical Explanations for the January Effect

Tax-Loss Selling Theory

Window-Dressing Theory

Information Release Effect

Psychological Theories

Evidence of the January Effect

Historical Data Analysis

Geographic Variation and Its Effects

Sector-Specific Observations

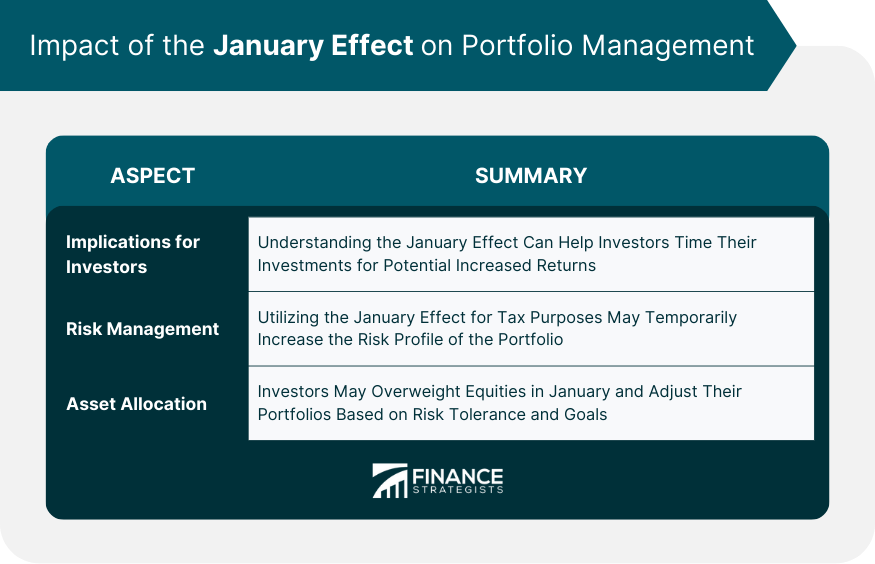

January Effect and Portfolio Management

Implications for Investors

January Effect and Risk Management

January Effect and Asset Allocation

Criticisms and Controversies Surrounding the January Effect

Efficient Market Hypothesis and the January Effect

Outliers and the January Effect

Criticisms Based on Recent Studies

Recent Developments and Changes in the January Effect

Impact of Changing Tax Laws

Influence of Globalization and Market Integration

Effect of Technological Advancements

Conclusion

January Effect FAQs

The January Effect refers to a financial market anomaly where stock returns, particularly in small-cap companies, are generally higher in January compared to other months. The phenomenon is theorized to be driven by tax-loss selling, window-dressing, information release, and psychological factors.

While there is evidence supporting the existence of the January Effect, it does not guarantee returns and comes with its own set of risks. Investors should consider it as part of a broader investment strategy rather than a stand-alone approach. Recent studies suggest that the effect may have lessened due to increased awareness among market participants.

The Efficient Market Hypothesis argues that all relevant information is already incorporated into the stock prices, making it impossible to consistently achieve returns above the average market returns on a risk-adjusted basis. The existence of the January Effect contradicts this theory because it implies that investors could theoretically achieve above-average returns by buying stocks in January.

Tax laws have a significant impact on the January Effect because one of its primary drivers is tax-loss selling, where investors sell stocks that have declined in value to offset capital gains. If tax laws change the tax year-end from December to another month, the selling pressure might shift, potentially impacting the January Effect.

Technological advancements like robo-advisors and algorithmic trading could potentially diminish or amplify the January Effect. For instance, if robo-advisors are programmed to rebalance portfolios at year-end, this could increase selling pressure in December and buying pressure in January, possibly strengthening the January Effect. However, the exact impact would depend on how these technologies are used by market participants.

True Tamplin is a published author, public speaker, CEO of UpDigital, and founder of Finance Strategists.

True is a Certified Educator in Personal Finance (CEPF®), author of The Handy Financial Ratios Guide, a member of the Society for Advancing Business Editing and Writing, contributes to his financial education site, Finance Strategists, and has spoken to various financial communities such as the CFA Institute, as well as university students like his Alma mater, Biola University, where he received a bachelor of science in business and data analytics.

To learn more about True, visit his personal website or view his author profiles on Amazon, Nasdaq and Forbes.